Last week, after a far-reaching, multinational investigation that began as a simple tax evasion case, fourteen FIFA officials were indicted by the American Department of Justice on forty-seven counts of white collar crime, including fraud, money laundering, and bribery. The case, the largest of its kind in recent memory, has brought widespread attention to the long-assumed corruption in soccer’s governing body. Allegedly, a number of voting representatives accepted bribes from potential host nations for the FIFA World Cup.

Yet when it comes to FIFA’s sins, corruption is the tip of the iceberg, though admittedly the most prosecutable. In fact, the sum total of bribes taken by FIFA officials pales in comparison to the material legacy of Brazil’s 2014 World Cup: $3.6 billion of infrastructure built specifically for the tournament that now languishes in near-total disuse. The Mane Garrincha Stadium in Brasilia, constructed at an estimated cost of $550 million of public funds, is now a parking lot, and the few stadia that are still in use as soccer venues draw comically small crowds. The 40,000 seat Pantanal Arena in Cuiaba attracts between 500 and 1,000 spectators per match. At present, many sites are expected to be sold off to private companies at a fraction of their cost.

Brazil is not the only country to encounter World Cup waste of unfathomable proportions. In fact, it’s become somewhat expected in recent years. Though initially touted as a springboard to economic renewal, the cost and fate of South Africa’s stadia are virtually identical to those of Brazil. Cape Town Stadium loses its government between $5 and $10 million each year.

Tallest buildings, fastest plans, biggest stadiums–all flaunt the audacity to suspend pragmatism

So why invest so much into an event that routinely offers such little payoff? A clever mod for Civilization V helps explain some of the motivations and effects of ill-conceived and poorly executed modern megaprojects. The “FIFA World Cup Host Resolution,” available in the Steam workshop from modder “Steph,” takes aim at FIFA’s institutional dysfunction. In the modder’s words: “What I bring is the opportunity to dive head first into the most drama-filled element of the World Cup: the bidding war to host the tournament.”

Here’s how it works: once “Biology” has been researched and access to oil secured, any player can petition the world congress to enact the FIFA World Cup Resolution. Once passed, players can devote production (read: bribes) to the project like they would any other “wonder,” which is what the game calls massive projects periodically undertaken by the player. Whichever player contributes the most secures the opportunity to host the world cup. Their reward? Twenty gold in “corporate sponsorship,” a pittance by Civilization V’s mid-to-late game standards, and the ability to purchase (not build) “Migrant Workers,” who receive an extra move each turn that represents the extra hours they are forced to work with little legal recourse. As the mod’s creator writes, “[migrant workers] are the foundation on which your brand new stadiums rest—or at least their bodies will be.”

Bleak? No doubt. But what’s most useful about the FIFA World Cup Resolution mod is how it comments not only on the decaying legacy of misguided and mismanaged international sporting events, but also the historical motivations behind their continued existence. By adopting the form of the “wonder,” the mod sets the World Cup in a historical lineage that includes two millennia worth of mega-projects, such as the Hanging Gardens or the Colossus. As veteran Civilization fans will tell you, though most players rush towards completing wonders as fast as possible (especially on lower difficulty settings), they aren’t always very practical: pouring resources into, say, the Pyramids often precludes building crucial pieces infrastructure, especially in the early game.

Yet the simple thrill of being the first to build the biggest projects Civilization V offers is often justification enough. Now and then, what lies at the heart of the transhistorical human fascination with unpractical but impressive public works is the superlative. Tallest buildings, fastest plans, biggest stadiums––all flaunt the audacity to suspend pragmatism, which helps explain why nine out of ten mega projects, according to Bent Flyvbjerg, a professor of management at Oxford’s Saïd School of Business, are massively over budget and years behind schedule. Megaprojects are much easier to start than they are to stop; engineers are eager to flex their technical muscle and politicians are quick to claim the visibility they offer.

The flow of play in Civilization V captures something of this. Most players, myself included, are guilty of letting a city suffer for the sake of whatever wonder it’s building, even if that wonder is less than integral to national “progress.” Even so, the payoff usually justifies the expense, at least from a quantitative perspective. Yet whereas the benefits of wonders (e.g. boosts in culture, revenue, border growth––each neatly quantified) included in the un-modded version of Civilization V are unproblematically positive, the effects of the FIFA World Cup Resolution mod are double-edged. The chief benefit it provides is low-cost human capital: the migrant worker. In other words, the “benefit” is the normalization of worker exploitation. Good for managers (and for the player), yes, but bad for workers.

From a historiographic perspective, Civilization V’s biggest fault is that it’s dogmatically materialist, unflinchingly determinist, and has little space for that which cannot be measured (even something as ineffable as culture is explicated via formula). But through its clever inversion of the cultural logic of the “wonder,” Steph’s caustic mod turns Civilization’s procedural historiography against itself and so constitutes a form of what the media theorist Alexander Galloway calls “counter-gaming.” The conventional poetics of gaming find themselves supplanted by a critical, alternative type of play.

Audacious projects require audacious sacrifices

The mod’s manipulation of the cultural and political apparatus of the wonder embedded into Civilization V’s gameplay thus calls into question the motives for the any megaproject, the majority of which have been impractical and built with what we would now call exploitative labor practices. In doing so, the mod reveals a nugget of historical wisdom: the cost (and benefit) of the wonder/megaproject is the willful suspension of pragmatism. Audacious projects require audacious sacrifices––monetary, ethical, or both––but the allure of a wonder provides ample justification to expend that cost.

Does that mean all mega-projects are misguided? Not quite. It’s perfectly true that the Sydney Opera House was 1,400% over budget and, for a time, was the bête-noire of its architect’s career. In its day, Sistine Chapel was a financial folly: Michelangelo swindled Pope Julius II out of an unimaginable sum, leaving the Vatican’s struggling treasury nearly bankrupt. The difference, though, is that those projects had (and have) a future. The empty arenas in South Africa and Brazil don’t. Each is an exceptional edifice erected for an exceptional event, and when that event ends, their purpose dries up. What remains is a handful of bodies sitting in a stadium designed for legions of international fans, their cheers echoing into empty space. Though far from populist, the Sydney Opera House and the Sistine Chapel (both included in Civilization V) have enjoyed a longer half-life through their integration into the textures of everyday life.

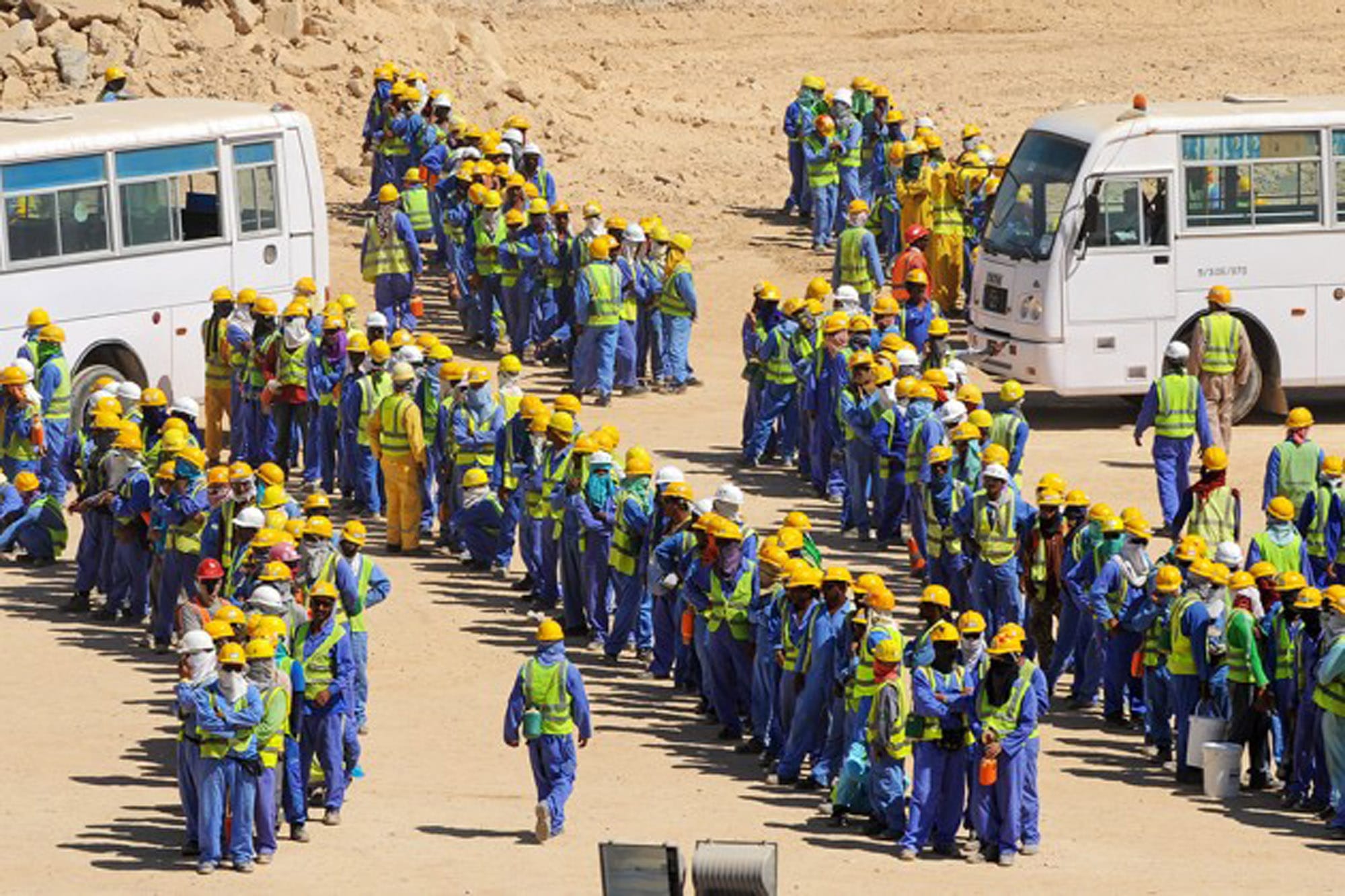

As I write, 1.2 million migrant workers are laboring in Qatar to prepare the necessary (and unnecessary) infrastructure for the 2022 FIFA World Cup, which will include nine new stadiums (and three renovations) that can accommodate over 600,000 spectators, roughly a third of the country’s usual population, as well as an entirely new city, Lusail, at an estimated cost of $45 billion. Beyond its ostensible purpose, the sparkling stadiums and cities will function as a highly visible declaration of national achievement for the country with the world’s highest per capita income (and lowest ratio of nationals to foreigners, mostly migrant workers, at a staggering one to six).

Since 2010, over 1,200 foreign workers have died. According to one estimate by The Guardian, another 3,000 will likely perish by the time fans arrive in November 2022. Explaining its deviation from the World Cup’s usual summer schedule, FIFA argued that Qatar’s estival temperatures were too hot for players, though apparently not for laborers working on buildings they will never enjoy for themselves. Someone has to pay for our pleasure.

The material legacy of Qatar’s World Cup is uncertain––some stadia, supposedly, will be dismantled and donated to countries with less-developed sporting infrastructure––but it’s undeniable that Qatar will have little use for a circuit of stadia that has three seats for every citizen. If completed as planned, Lusail alone could house every Qatarense national and then some. What seems more likely is another set of empty arenas and a dusty, half-filled metropolis baking under the Arabian sun; a grander and more lonesome version of Dubai’s derelict construction sites and parking lots filled with abandoned luxury cars.

What’s so civilized about that anyway?