How DreadOut combines Indonesian horror with the PlayStation 1

In middle school, I once had an online friend with a ghost-hunting hobby and a self-diagnosed case of dissociative identity disorder (DID). She would often post photos from her expeditions on the gaming message board I frequented, explaining the stories behind her subjects to the uninitiated. Occasionally, her posts would lapse into diction other than her own, indicating that her alternate personality was in control. As with her ghost sightings, opinions regarding her authenticity were split 50/50; it doesn’t take much Photoshop skill to create a low-res photo of the White Lady, and any imaginative teenager on an internet message board can play pretend. But a decent chunk of us wanted to believe (I should also mention that this girl was a huge X-Files fan).

Teenagers enjoy being scared. It’s why they’re the prime market for horror films and games, as well as cheesy Halloween events at amusement parks. I had a friend in high school who enjoyed exploring abandoned hospitals—your standard slasher setup. Teen horror has always essentially been Rebel Without a Cause with murderers and ghosts mixed in. Whether or not adolescent thrill-seeking was a thing before James Dean and Jason Voorhees made it cool is a chicken-or-the-egg debate. Whatever the case, it’s as American as Wonderbread.

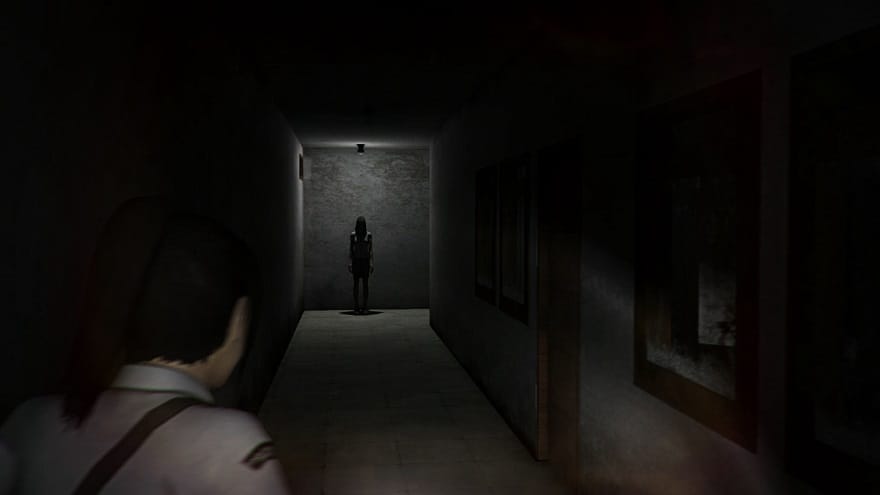

But in DreadOut—an upcoming horror game from Digital Happiness, an Indonesian studio—this story plays out on an unspecified island in Indonesia. Try and guess the story beats: first, a group of high schoolers on a vacation trip (inexplicably still wearing their school uniforms) decide to take a detour from their designated path; second, they wind up in an old, deserted town; third, they are split up and promptly terrorized by otherworldly forces; fourth, the protagonist discovers that only she can quell the oppressive spirits and save her surviving friends. Still, the game is a case-in-point for the rise of the Indonesian horror genre, which refracts as much as it reflects American horror.

Indeed, DreadOut seems to enjoy toying with the obligatory nature of its setup. It opens with a fakeout nightmare sequence lifted from Silent Hill; the protagonist wanders through an abandoned house in the dead of night and encounters a shrieking banshee with a face like the mask from Scream; she then awakens in a van with her thoroughly hammy friends. As the group begins to disembark in the deserted town, one of the girls lackadaisically slams the car door in a boy’s face—a touch of slapstick to show that we’re not dealing with any tortured James Sunderlands or burly Isaac Clarks. Your life isn’t in danger; you’re just at Halloween Horror Nights with your friends from homeroom.

DreadOut’s central mechanic—defeating ghosts by snapping pictures of them—is a clear and oft-noted nod to the Fatal Frame series, but there’s clear reverence for the entire canon of late Playstation and early Playstation 2 horror titles. The camp-factor of the opening sequence recalls a time when kitsch didn’t dilute fear. The game’s theme song (remember those?), a single recorded by an Indonesian band named KOIL, is a melodically grim dirge in the Silent Hill tradition. And the horror genre has a long tradition of sending girls alone through long dark corridors—Parasite Eve, Clocktower, Silent Hill 3, and so forth. Amber Lee Connors, who directed DreadOut’s stateside dub, cites Haunting Ground and Rule of Rose, two milennial horror titles, as major influences. The PC horror renaissance is interesting, with its unreliable first-person perspectives, but there’s something to be sad for this fertile era of digital horror. Digital Happiness’s revisitation is both a tribute and an intriguing shift in context.

Digital Happiness’s revisitation is both a tribute and an intriguing shift in context.

Indonesia’s game development scene, much like its film industry, has only recently begun to make a name for itself. Both are late bloomers due to a national history of conflict, wherein presiding empires shuffled just about every other decade. This stunted the growth of the film industry, which at any given moment was either co-opted for the purpose of propaganda, or overshadowed by imported films. But since 2000, Indonesian filmmakers have begun to establish an identity within genres lifted from Hollywood.

Indonesian horror films have begun to garner notoriety in recent years, with independent filmmakers gaining name recognition in neighboring nations. Stateside, horror buffs may recognize Timo Tjahjanto, whose short film Safe Haven appeared in the horror anthology V/H/S/2. Like his debut film, Rumah Dara, it’s a blood-soaked portrayal of the rift between contemporary Indonesians and their fragmented cultural tradition. In Safe Haven, documentarians filming a secluded cult compound fall victim to its demonic rituals. In Rumah Dara, two newlyweds en route to an airport are stopped in the middle of the road by a woman in need of a ride; they escort her to her home on the outskirts of Jakarta and are promptly kidnapped by her family, who wish to cannibalize them in pursuit of eternal life.

Some ghosts infiltrate technology to voice their pleas to the mortal world. This happens particularly often in Japanese horror: in Kairo, ghosts spill out of the overcrowded spirit world and into the internet; Ringu’s Sadako (who became Samara in the American remake) used VHS tapes to spread the truth about her murderous mother. They use it the way we do: as a tool for communication.

But in Indonesian horror, ghosts are hostile towards technology. The documentarians in Safe Haven are ignorant and intrusive. In the 2006 film Kuntilanak, the eponymous ghost haunts an abandoned factory whose workers perished in a fire during Indonesia’s industrialization. Kuntilanak also shows up in DreadOut, but her history goes back much further than the 2006 film, into the country’s very folklore. She has a lot of origin stories, but the one DreadOut adheres to is this: when Kuntilanak was alive, she was raped and impregnated by a corrupt landlord. Her neighbors, believing illegitimate children to be harbingers of bad luck, buried her alive. Kuntilanak’s spirit now haunts men, in search of vengeance for the one who wronged her.

She’s a fixture in Indonesian horror films—arguably achieving Freddy Krueger status, after being pitted against another traditional ghost in Pocong Vs. Kuntilanak. In that film, the two ghosts are summoned as a dare between reckless teenagers, and exorcised through the reconciliation of an ages-old family feud.

But in DreadOut, Pocong and Kuntilanak are undone by a smartphone. As the player, you wield technology as a weapon, carrying out the modernization that fuels the spite of the spirits. Would Kuntilanak be averse to having her picture shared on Facebook? Probably. But perhaps there’s a difference between hunting ghosts and sharing their stories, between trophies and memorials.