How To Escape

Early on in John Darnielle’s 2014 novel, Wolf in White Van, there is a strange but inescapable echo. Sean Phillips, the book’s protagonist, lies on his back in a hospital bed, a mysterious accident having put him there. Unable to move or leave, the ceiling of his room becomes a kind of landscape for him, a potential space for imagining. As he stares up at it, he envisions the growth of mold and mildew, following patterns already laid into the uneven paintwork. From here the ceiling begins to stretch out in his imagination, connecting to the ceiling in the next room, and the next room until it provides a mental escape: “the sky at night gone flat and painted white, the constellations in the cracking paint, the dust the cracks bring into being as they form, finding free land where none had been before their coming.”

This echo is one of a book written almost 60 years before, far from the bleak American plains of Darnielle’s work. In Boy in Darkness, a novella by Gormenghast writer Mervyn Peake, the titular boy dreams of escaping from his imprisoned life of endless ritual. Staring up at the ceiling, he too begins to interpret the stains and mildew that live across its widening expanse. He watches as a fly (“An explorer, I suppose”) crosses this inverted landscape, travelling across archipelagos of mold and seas of fading paint. As he does, the spirit of adventure begins to grow in him, his thoughts becoming the impossible to refuse: “the boy became dimly aware of exploration as something more than a word or a sound of a word, as something solitary and mutinous.”

the ceiling begins to stretch out in his imagination

Its more than a coincidence that these two writers, split by time, space and the Atlantic Ocean, both found the inception of their character’s escapism in a moldy ceiling. Of course, it is possible that Darnielle is referencing Peake, sneaking in a knowing nod to a master of fantasy—however I suspect the reference is far too obscure for this to be the case. No, in reality the connection is far more obvious. In both stories the young main character is somehow rebelling against the tireless routine of everyday life. In Wolf in White Van this is represented by small town horizons, while in Boy in Darkness it is the rituals of young royalty. Both present characters who believe, with every fiber of their being, that there must be something else, something more than this. For those who grew up on the alternate worlds of videogames, movies and fiction of all kinds, it is a familiar feeling, one that grew with you as these stories leaked into the daydreams and fantasies that filled the gaps between home and school. Across generations, people can recall those moments in which they were truly immersed, separated from reality by a constructed world. All that was needed was a fertile space for the imagination to roam free. In Wolf and Boy that space is a ceiling.

However, it is more than likely that, for you, this space is a screen. Whether through the infinite canvas of the internet, or the ever-receding vanishing-point of 3D worlds, the screen is a membrane through which we pass every day. In some ways it is the purest symbolic object, literalized into a concrete reality: It is nothing more than potential space, a rectangle on which anything may be cast. Like the photograph and the page before it, it has the potential to hold more than it can ever show. In this way, the screen forms part of a heritage of escapism that stretches into pre-digital culture and beyond, perhaps reaching, in some far-flung history, the flickering shadows of Plato’s cave.

Yet the screen is also fundamentally unlike these other spaces of potential escape: In its function as a portal it is both elegantly luminous and clumsily literal. It is a matter of interpretation—while Boy and Wolf’s mouldy ceiling presents a space constructed by both intention and chance, signal and noise, the screen so often presents a total space of intention. In the ways we use screens every day, the things they depict are placed there by human hands with the express purpose of displaying them. Randomness is limited to the serendipity of news feeds and social media scrolls, spaces that are becoming ever more controlled by invisible algorithms. In the case of videogames, “player agency” may buzzword its way onto press releases and retail boxes, but its true existence remains greatly exaggerated in worlds handcrafted to manipulate. Its not that the screen is an inherently restrictive space, but for the aims of staging an escape, it does have its limitations. We may, in desperation, throw ourselves again and again at its high-fidelity worlds, but somehow we always seem to remain on the outside, looking through the window at a land beyond reach.

So, if the screen is a barrier we will never pass through, what chance do we have of staging an escape like the protagonists of Boy and Wolf? Perhaps the very medium that brings those two characters into existence is our answer: The page has long been the refuge of the downtrodden, an escape from an unforgiving world. Many have written on its power, but the ancient Arab proverb “A book is like a garden carried in the pocket” is among the most succinct. The escapism of the page is forged in the indirect nature of language, which exists as a kind of code for creating narrative, rather than a narrative in itself. We become so familiar with reading it that we no longer see this distinction, looking past the text to the fake reality beyond. Like in The Matrix, we don’t see the code anymore, all we see is “Blonde, brunette, redhead.” This kind of writing has become termed “absorptive,” for the way it allows the reader to enter into it painlessly, receiving only the effect of language, not language itself.

you could hardly consider yourself to have “escaped.”

Yet once you are psychologically “absorbed” by a text, you could hardly consider yourself to have “escaped.” Especially for those used to interaction in their fictional worlds, the pleasures of visiting a reality through the straightjacket of the page can be stifling. Even disregarding this, the limitations of “absorptive” fiction are manifold. With style kept to a minimum, events arranged in the learnt patterns of five- and three-act structures, and the protagonist limited by their ability to be “relatable,” escapist books are often artlessly constructed. This is not to say that escapism is without cultural value, but that in the form of literature, escapism so often brings with it atrophied and conservative prose. The page may be able to absorb readers better than the screen can watchers, but it does so by denaturing itself, and sacrificing the powerful challenge and play of language.

All of this leaves us with a limited potential for escape. Sure, we can marshal the spaces of the screen or the page, but we are ultimately trying to escape reality through mediums that can never fully allow that transition. What we are left with is the suggestion first presented to us in both Boy and Wolf—the ceiling. But, if we look closer, it is not the ceiling itself that facilitates the escape in both of these protagonists’ stories—the ceiling is standing in for something else. It is little more than a surface, one that happens to be the biggest, emptiest, closest surface in both characters’ lives. Look around the room you are sitting in. Even if you are unnaturally clean, the ceiling will easily be the cleanest, largest, emptiest space in your vicinity. This emptiness is what makes it so powerful. Living a modern life, surrounded by the clutter of a hundred things, each linked to a network of hundreds of other things, empty space takes on a powerful symbolic value. In both Boy and Wolf, all the protagonist needs to do is look away, to look towards empty space. If we have a chance at escape, perhaps this is it.

But this empty space we might turn to is a double-edged sword: It is in emptiness that the self is at its most dangerous. Boy in Darkness and Wolf in White Van don’t only share their ceiling. They also share a darkly pessimistic view of the potential of adventure and escape. Both books are enamored by it, seduced by its promise, and yet neither book presents an entirely positive view. Instead they stress the dangers of disconnecting from reality and the unknowable nature of the self. It is even written into their titles: The wolf in the white van and the boy in the darkness are both aspects of their protagonists, brought to life by a desire to escape, whatever the cost. If we wish to follow in their footsteps, then we should be aware of what we might find, out there in the emptiness. T.S Eliot, one of the foremost chroniclers of the emergence of modern life, puts it best in his poem Preludes:

“You tossed a blanket from the bed,

You lay upon your back, and waited;

You dozed, and watched the night revealing

The thousand sordid images

Of which your soul was constituted;

They flickered against the ceiling.”

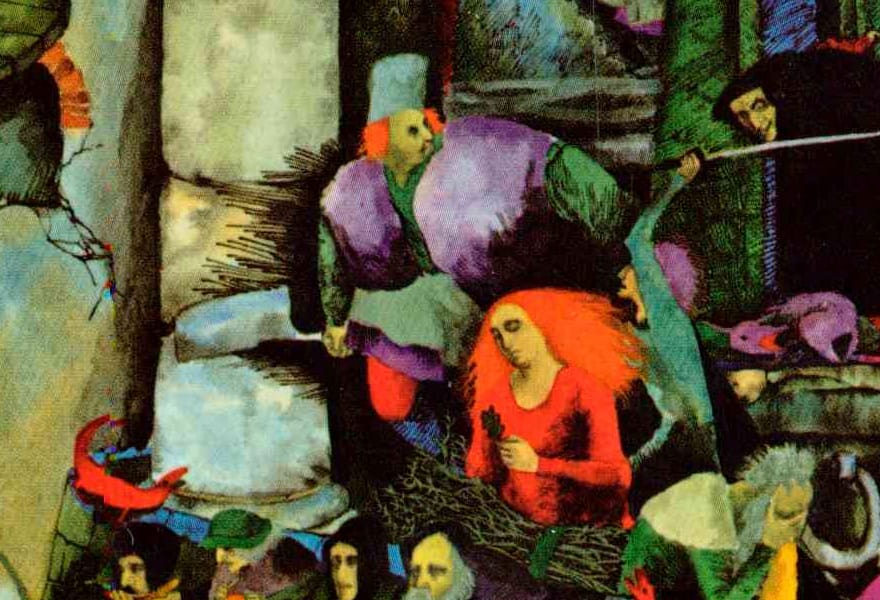

Images are taken from Bob Pepper’s cover illustrations on the out-of-print editions of the Gormenghast trilogy published between 1967 and 1969.