Tom Francis’s unassuming PC stealth game Gunpoint is ostensibly about rewiring electronics and outsmarting security systems. Only Richard Conway, freelance spy and trader of secrets, is not the most professional agent. He starts the game’s events by crashing out of a plate glass window, landing flat on his face, and then denying it over the phone to someone who watched it happen. You’re not supposed to take him seriously.

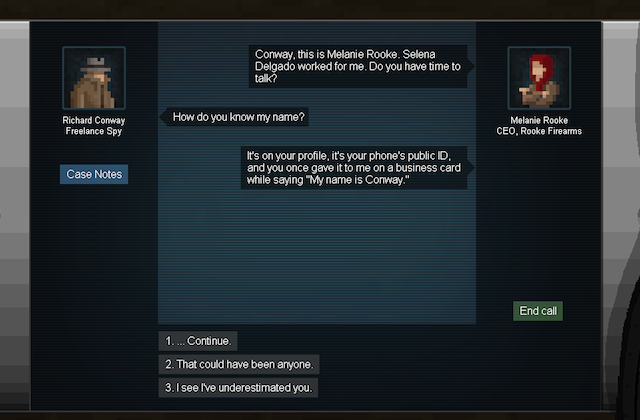

Yet Conway finds himself involved in the murder of Selena Delgado, whose case segues into a dirty rivalry between two gun companies, police corruption, and scandalous love affairs. Players communicate with potential clients behind a virtual wall—often via text message, with blurry avatars, which punctuates the anonymity of the job. Even the perpetual hammering of rain, with the music down low, sounds like the patter of a keyboard in a desolate computer chat room.

Players communicate with potential clients behind a virtual wall.

In Gunpoint, the very title is a contradiction. Guns are not the point. It’s clever: in the midst of America’s firearms obsession, Francis creates a game about them that facilitates and encourages better solutions than shooting.

Guns are not the point.

The serious moral choices players must contend with—whether to free the wrongfully imprisoned, to assist both sides, or to kill or incapacitate witnesses—are at odds with Conway’s inappropriate sense of humor. At times, slapstick prevails. Conway jumps to ludicrous heights with his Bullfrog brand hyper-trousers, pancaking on the pavement unscathed with a meaty smack. Upon contemplating the possibility of a murder charge, he quips, “I agree that I am boned.”

That dash of humor belies a troubling vision. This is a world where everything is hackable and security personnel carry palm-recognizing firearms, which you can remotely rig so they trip light switches instead of firing bullets. The triviality of this undertaking is a crippling thought, and it’s more frightening when you realize that those guns are our reality. They’re called smart guns. Factor in the National Security Agency’s recent spying with PRISM and a massive leak from former defense contractor Edward Snowden, and it’s clear that privacy and safety are fragile constructs both in Conway’s world and our own.

It’s clear that privacy and safety are fragile constructs both in Conway’s world and our own.

We might brush through these themes, eager to continue playing, but the more conscientious can take comfort in how much Gunpoint discourages its own violence. Players can’t acquire a gun until later in the game, when you’ve earned enough cash from fulfilling contracts to purchase one, and Gunpoint favors stealth over conflict. In this alarming techno-future, guns are outlawed. Some clients will even rank your performance down if you cause too much noise or inflict physical harm. In fact, the moment you decide to take the “easy” way out and mow someone down, an unknown sniper targets you, ticking down the seconds before you fall prey.

The more conscientious can take comfort in how much Gunpoint discourages its own violence.Despite my natural impulses to open fire,

shooting freely is unwise. Yes, one hit will suffice, and you can rewind deaths and mistakes by selecting autosaves (conveniently clocked by the second) as if none of it matters. However, cleverness trumps brute force. It’s a twist on the old arcade game Elevator Action, where you shoot enemy agents as they pop out of doors in a 30-floor building. Although the goal is identical in both games—retrieve a set of documents and plan your escape—the constant turnstile rotation of enemies and the cramped quarters in Elevator Action ensure constant face-to-face confrontations. Killing is mandatory. The sequel, Elevator Action II, is even bloodier, with no qualms about its barbarity.

Shooting freely is unwise.

Yet in Gunpoint, that’s not the focus. Each well-protected building is your toy to play with. You can flip switches to plunge guards into darkness, climb on walls, crash through windows, hide in elevators, and wire nearly anything together so that a single action produces a more desirable result.

Consider the following chain of events: You hit a lightswitch and leave the guards in the dark. They go to flip the switch, and it opens a trapdoor instead. You fall into the room, set motion-sensors so that they lock or unlock doors, enclose the guards in rooms with no means of escape, and ultimately square them all away so you can get in and out and do the job clean.

Conway only does what you tell him to. He doesn’t choose who lives or dies. But I do, and the game gives me the choice and means to curb its violence.

I killed eleven people in my playthrough but injured twenty-five and spared others. “I didn’t get the trigger man,” Conway wrote in his blog after the credits rolled. We were both holding the pen. “It was the only play I could stomach. Wish I could say it was the right one.”

He mused, “I guess I picked the least shitty of two incredibly shitty sides.”

“Maybe that doesn’t matter. Maybe all that matters is that I now have the ability to kick down doors.”

“Either way, I need a drink.”