Videogames and sports are kissing cousins and are part of the same family of life known as play. With the rise of esports, the conversation about the ways that PC games can learn from the likes of football and baseball has renewed. Over the next few weeks, iQ by Intel and Kill Screen will explore how these worlds intersect, whether they know it or not.

In Madden NFL 2005, EA introduced a new feature called the “Hit Stick.” It let you flick the right thumbstick to violently launch your defender at an opponent. When executed correctly, the screen shakes; the controller vibrates; the crunch of flesh and pads erupts from the speakers; and, upon contact, the offensive player crumbles like a rag doll. His body just folds and collapses. The effect is immensely satisfying.

I remember I gasped when I saw the hit

There was nothing pleasurable, though, about the time Stevan Ridley crumpled like a ragdoll. It was late last season, when the New England running back collided, helmet to helmet, with Ravens’ safety Bernard Pollard. I remember I gasped when I saw the hit, when I saw Ridley spin and flop forward onto his right leg, when I saw him drop the ball as his body went limp as he fell onto his back. Lying on his back as the play finished, concussed and knocked out cold, Ridley’s arms flexed awkwardly, almost reflexively, as his legs bent with a strange inhumanity. He looked like a videogame ragdoll—like a character procedurally rendered lifeless.

We’re two weeks into the NFL season, and fans are excited as ever. But this year, the specter of concussions, and the subsequent long-term side effects, haunts the league. Amid all the pomp of the first Sunday of games were reports of a $765M lawsuit settlement with former players and stories about how the NFL is trying to downplay the danger of the sport. Last month, ESPN unexpectedly pulled out the production of a documentary about concussions in the NFL, reportedly under pressure from the league. And just on Sunday, Green Bay Packer Eddie Lacy got knocked out of the game thanks to a high hit from Washington’s Brandon Meriweather (who later left the game because he also suffered concussion).

There is still a major problem that the NFL faces regarding concussions—the game of football is popular because it is violent.

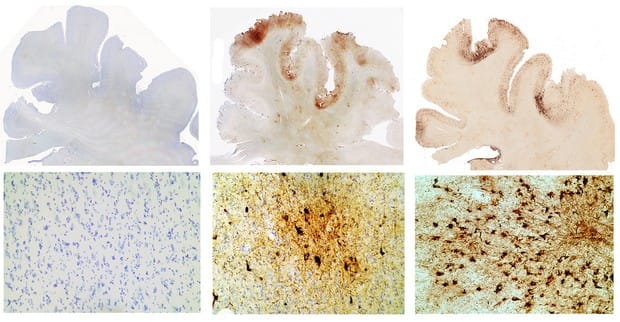

The effects of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy [CTE]—which include memory loss, confusion, impaired judgement, aggression, depression and dementia—have been tracked since the early part of the 20th Century. But over the past six years the NFL has been working, albeit slowly, to address growing popular concerns, and to protect players’ health. In 2007, the league changed rules so that a player knocked unconscious during a game could not return. While this was certainly a step in the right direction, many serious concussions do not render a player unconscious, and so over the years the league has been adopting more restrictive rules about tackling with the helmet, and about how players who receive concussions are handled by teams. The NFL is also pursuing research and technological approaches to making the game safer. The league is investing many millions in researching CTE, and has teamed up with Intel to develop safer helmets.

Despite all of these efforts, and despite shifting cultural attitudes about concussions, there is still a major problem that the NFL faces regarding concussions—the game of football is popular because it is violent.

For every million dollars spent on research to protect players, those efforts are subverted every time a commentator explodes with excitement, or screams “He got JACKED UP!” after a particularly violent hit. Efforts to protect players are subverted whenever players whoop it up, slap each other on the helmet and celebrate an explosive tackle as fans scream and cheer. The NFL tries to to balance on the tightrope of safety while exploiting the violence of the game that made it the most popular sport in America.

Is the videogame complicit in the exploitation of violence for popularity?

And what about Madden? Is the videogame complicit in the exploitation of violence for popularity? Of course the characters in the game are not real, and nobody really gets hurt, but we should remember that the characters are likenesses of real players in a simulation of a very real game.

Madden NFL 12 addressed the issue of concussions and CTE somewhat, as concussions became an injury that players could sustain in the game. John Madden (the human, not the brand) told the New York Times that the inclusion of concussions in Madden NFL 12 was intended to help educate young players about the risks of head injuries. Phil Frazier, then executive producer at EA Sports, said that dangerous tackle animations were removed, but concussion injuries were put into the game as a “teaching tool.” The thought is that young players of Madden who might play real football could learn about the dangers of head injuries as they develop as athletes. Cyncis could say this was just PR maneuvering, but the efforts did appear to be sincere honest.

Frankly, the adjective “bone-crunching” should never be considered positive.

Despite all of this, we come back to the inherent contradiction of a sports culture that celebrates the violence of the game while pledging that the health of players is their greatest concern. Concussions are a physical problem, but they are very much a consequence of action encouraged by a sports culture of violence. Youtube videos of Madden “big hits,” E3 trailers that feature montages of violent tackles, and a gaming press that extols “hard hits, and windmilling mid-air crashes” all reinforce the ideology of virtuous violence in American football. Frankly, the adjective “bone-crunching” should never be considered positive.

Wanting Madden to rise above the hyperbolic culture of violence in professional football may be asking too much of a videogame, especially given that we’re talking about, well, videogames, which can be pretty violent. But increasingly, videogames are appreciated as cultural artifacts that don’t just reflect the values of a society, but also shape those values. If the push to include a message about concussions in Madden NFL 12 shows us anything, it is that developers understand the unique capability of games to communicate messages. We don’t need Madden to become a flag football videogame as a principled statement against the violence of the sport, but if more small steps are taken to downplay the violence, it can contribute to a shift in cultural attitudes.