How Japan shaped nostalgia in games

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel.

For Shigeru Miyamoto, the inspiration for The Legend of Zelda (1986) series lay in the natural beauty of his hometown of Kyoto, Japan. As a young boy, the Nintendo designer behind Mario, Zelda, and Pikmin would take hikes around nearby forests, rivers, and old Sonobe Castle ruins. It was on one such hike that Miyamoto happened upon a cave that fascinated him. He returned to it a few days later, shook off his nerves, and, armed with a homemade lantern, journeyed into its mysterious depths. It was this feeling of discovery and awe that stayed with Miyamoto throughout adulthood, ultimately inspiring the games that would change the medium forever. From Chrono Trigger (1995) to the Persona series, nostalgia went on to characterize many classic Japanese games

Closely linked to the idea of “mono no aware,” nostalgia describes a ‘gentle sadness’ at the impermanence and transience of life. A sensitivity to nostalgia is even prominent throughout Japanese manga and literature, often invoking a sense of longing for the good old days. Due to the nation’s large cultural influence over the medium, a love for nostalgia spread globally in games, influencing designers everywhere for years to come. As evidenced by the success of Toby Fox’s Undertale last year, childhood continues to be a source of inspiration for gaming’s most talented creators.

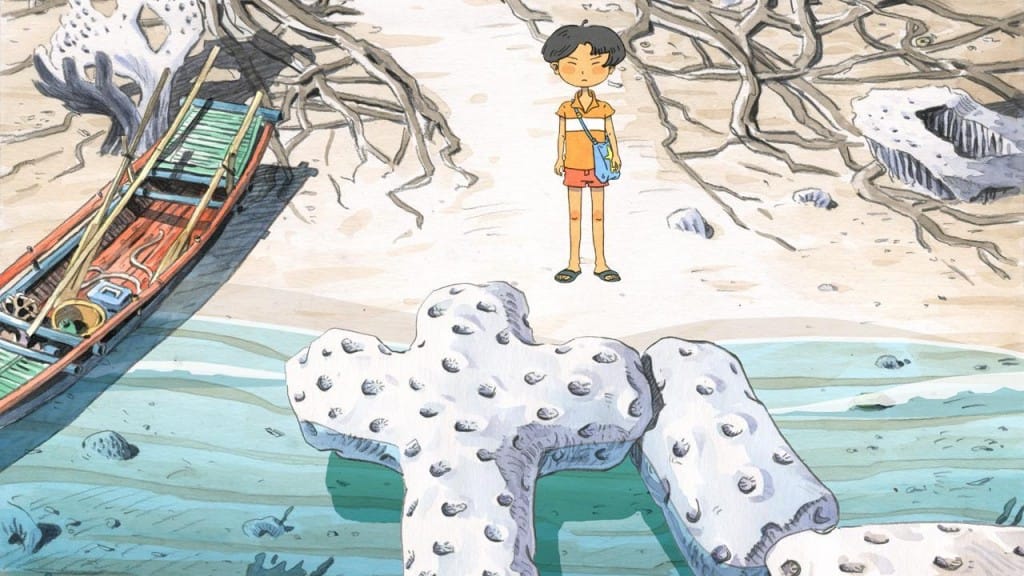

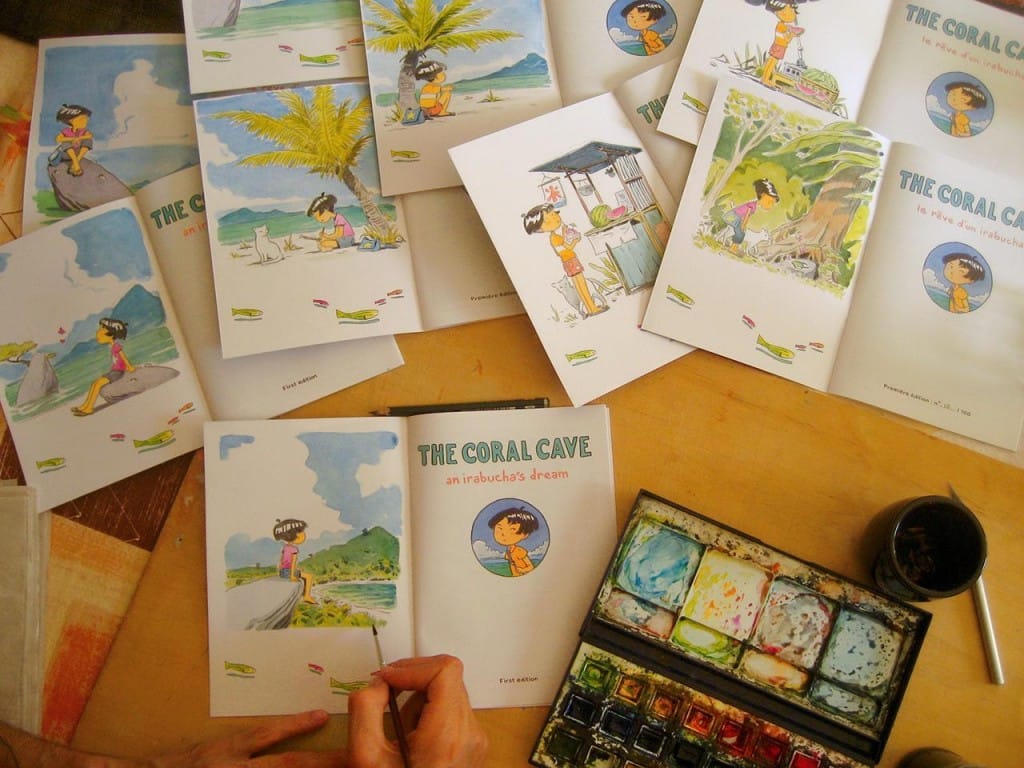

The small French studio Atelier Sentô, designers of the painterly Coral Cave, are also among those modern creators who took Japanese nostalgia to heart. “Like many people, we discovered Japan through its culture: the films, music, art. Japanese culture as we receive it in the West is interesting because it’s very different from what we know and at the same time it’s strangely familiar,” said Oliver Pichard, the team’s background artist and programmer. The Coral Cave is drenched in the warm glow of happy childhood memories. Set on a small tropical island off the main Japanese archipelago, it follows the adventures of a willful Okinawan girl as she discovers its secrets.

They found they had developed a taste for Japan’s unique nostalgic identity.

The sandy atolls and gently ebbing waters were painted by hand in watercolor, giving the player a tactile experience. The designers pointed to their deep affinity for Japanese manga artist Daisuke Igarashi, particularly his beautiful lines and portrayals of young people in the nautical world. There is one scene in the game in which the hero builds a bridge out of coral, while catching glimpses of a ghostlike woman from the Edo period beneath the waves. It immediately brings to mind the classic animated films of Studio Ghibli, yet another universally influential staple of Japanese nostalgia. A genuine sense of longing for these Pacific islands is evident throughout The Coral Cave. When the team was living as exchange students in Japan back in 2010, they were captivated by the quaintness of each island.

Pichard and Cécile Brun, the game’s character artist and animator, said they soaked up as many traditional festivals as possible while in Japan. In Okinawa, they were even given hand-drawn maps to find their way around. The tiny coastal getaway of Minna-jima in particular captivated them, as an island so minuscule one could walk from shore to shore in just a matter of minutes. “There was only one road on the island so we kept bumping into the same group of kids all the time. We started thinking about what kind of adventures they could have on that tiny piece of earth lost in the sea. That’s how the project was born,” Brun reminisced. When Brun and Pichard returned to France, they found themselves pleasantly haunted by memories of these islands. They found they had developed a taste for Japan’s unique nostalgic identity.

They missed everything from the wooden houses that aged quickly from the humidity, to the traffic lights that played children’s lullabies. Even the bone-chilling Siberian winds of Niigata that kept everyone indoors didn’t seem so bad in retrospect. They realized how the Japanese had “a different way of seeing life and time—a deep sense of the ephemeral nature of things,” said Pichard. They found their recollections took on an almost dreamlike quality because of it. So they did what artists do: manifested their dreams into reality. “Too often games are based on other games and not on personal experience,” Brun said. “It is difficult to care for a game with no emotion. It’s important to make games based on something that’s really important to you.”

Perhaps that focus on recreating profound experiences is exactly what makes Japan such a powerhouse in the gaming world. Japanese creators, particularly those of games from the 80s and 90s, bring the earnestness of their childhood memories into the work. Born out of a culture with such a strong sense of nostalgia, legendary designers like Miyamoto inherently understood that Hyrule needed to be a place that players would want to revisit again and again—like a favorite memory.