How memes emerge from games

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel.

A minute-long clip of Demetry James playing Madden Football from 2010 has been watched over eleven million times on YouTube. The video isn’t provocative or bizarre; all we see is a videogame version of Greg Jennings, then-wideout for the Green Bay Packers, catching a ball and running for a touchdown, hobbled by a broken leg suffered earlier in the contest. James provides commentary: “How is he running with a broken leg?… He put the team on his back.” By itself, the minute-long sequence is unremarkable, a glimpse into any after-school play session of your neighborhood buddy. But people found the clip hilarious and soon the video went viral.

“Shared context is necessary for humor,” says Christina Xu, co-founder of ROFLCon and faculty at the School of Visual Arts. “You kind of have to know the rules of a situation to understand why something is funny within it.” Over twenty years of annual titles has made the Madden Football videogame franchise one of the most known quantities not just in the game industry, but in all of entertainment. The selection of the new title’s cover athlete is covered by ESPN and MTV. Had James been playing Dominoes, nobody would have cared. Or laughed.

“Shared context is necessary for humor.”

The tone of our digital age irrevocably skews toward humor. Videogames, their players prodded to compete or cooperate, often provide a more fertile ground for shared experience than more traditional mediums such as literature or music. Xu sees the connection as no coincidence.“On an increasingly internationalized and segmented internet, games continue to be a shared space where the rules and characters are familiar to lots of people across many different backgrounds,” Xu writes in an email.

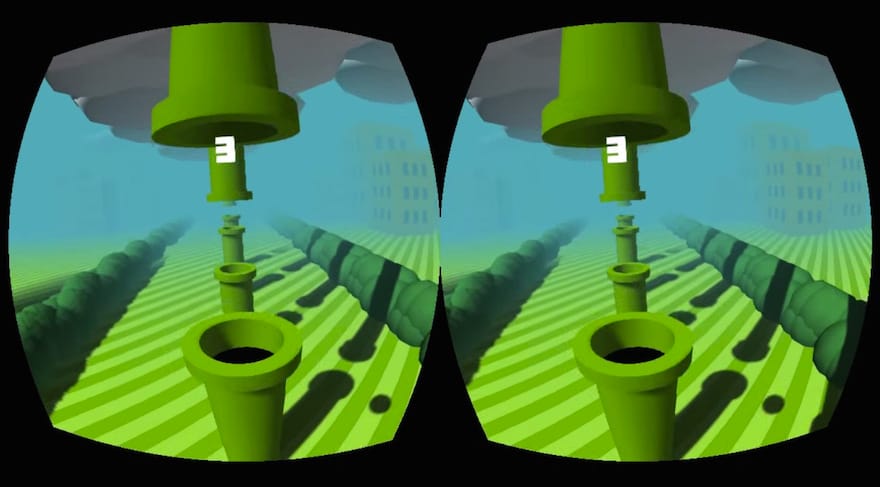

Last fall, Andy Sum took part in a game jam, an event where developers have a limited amount of time to create a working prototype of a videogame from scratch. His solution: borrow known images from online gaming communities and embed them into a generic first-person shooter. The result, cheekily titled Game of the Year, quickly devolves into a chaotic nightmare of floating text, flashing lights, and photoshopped video clips. To an outsider, it makes little sense. To someone familiar with the competitive online gaming scene, each bag of Doritos or photo of Jackie Chan’s face is understood as one joke after the other.

Game of the Year could not exist in the pre-internet age. It is forged from that most modern of materials: The meme. Richard Dawkins coined the term in his 1976 book, “The Selfish Gene,” its origin a Greek term for “an imitated thing.” Whereas Dawkins wrote about fashion trends and architectural styles as memes, the term has since come to be associated with the proliferation of remixed images as seen on sites like I Can Has Cheezburger, that collection of cat photos with captions started by Erik Nakagawa and Kari Unebasami in 2007.

What began as a lark soon grew into a movement, then a commercial empire spawning imitators. Soon companies like Nintendo were using image macros (the general term for an image with superimposed text) as a form of PR. What bubbled up organically was now an identifiable mode of communication to be co-opted and exploited. For gaming communities, it was a natural fit. “Humor and play don’t necessarily go hand-in-hand, but they’re certainly often found together,” Xu says. “They both often take advantage of subverting expectations and rules to create something unexpected.”

We play a videogame to be in control; the creation of and sharing of manipulated images can be seen as an extension of that desire for control. With the rise of independent development and the ease of downloading digital products, entire games can now proliferate in the way that images and videos have. “I think it’s more interesting when a game becomes a meme format in and of itself (like Flappy Bird),” writes Xu.

The creation of and sharing of manipulated images can be seen as an extension of that desire for control.

The super-hard, extremely-simple mobile phone game from Vietnamese developer Dong Nguyen came out in the summer of 2013; by January 2014, hundreds of cloned versions of the game were available, each with a slight variation: Frenchy Bird wore a beret and flew through Paris; Flappy Pig’s porcine protag barely gets off the ground. The limited success of these imitation games proves that, as with humor, timing is often everything. And even the freshest material grows stale with repetition.