How Crossy Road updates the timeless appeal of Frogger

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel.

Frogger, originally released by Konami in 1981, has since become not only a classic videogame, perpetually re-released on newer formats, but also a cultural icon, being referenced on popular TV shows, movies, and music. In an era where alien invasion and abstract consumption ruled the day, Frogger’s simple, grounded theme proved accessible and compelling; what works well as a joke set-up worked even better as a quarter-muncher.

Crossy Road came out on iOS less than four weeks ago; already, over nine million people have downloaded it. In all likelihood, Crossy Road will not linger in the minds of our collective consciousness thirty-three years later, as Frogger has. But right now, the free game by an Australian studio named Hipster Whale is spreading across the globe with a speed and pervasiveness its forebear could only dream of. Both feature animals navigating busy intersections. But aside from immediate, easy comparisons, they are surprisingly different experiences. By comparing this 21st century Frogger to Konami’s three-decades-old original, we can plainly see how technology has altered the way we consume and share entertainment.

Even Frogger predicted the “pay-to-win” mentality that exists in popular mobile games.

I spoke with Matt Hall, one half of Hipster Whale along with Andy Sum, from his home office just outside Ballarat, Australia. He can see rabbits and kangaroos and sheep from his window. No native animals have made it into their game, though. Yet.

“It’s Australia Day at the end of January,” Hall says, “[so] we’ll do an Aussie Pack.” Like other mobile studios, they plan to update their game to keep up with the seasons, and even add cultural happenings that are impossible to predict. This is one way they’ve rebuilt Frogger’s appeal. Digital games downloaded onto personal hardware can be nudged and tweaked throughout their life; an arcade game was largely static, a heavy hunk of plastic and circuitry that required physical alterations to the motherboard in order to update a game, at great cost to the owner.

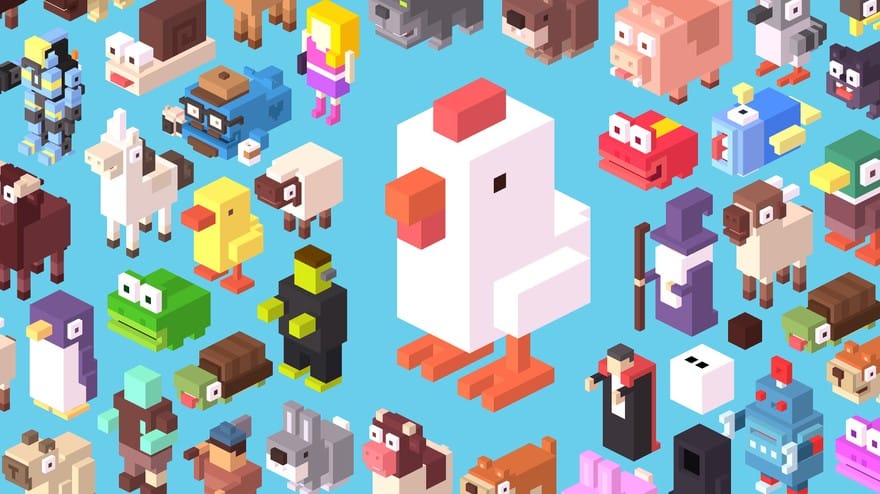

Crossy Road already incorporates characters based on popular internet memes or personalities, such as PewDie Pug (after YouTuber PewDiePie) and Doge, the nonsense-spewing Shiba Inu. Crossy Road can remain flexible, then, evolving in a way Frogger never could. And yet perhaps the largest differentiator between arcade classic and modern mobile hit is in the latter’s willingness to ape physical, tangible goods.

“My daughter has lots of Skylanders,” Hall says, referring to Activision’s line of figurines that can be used to unlock new content in a tie-in videogame. “She loves the game, and we’ve played it together a lot over the years, and that formed a big influence [for Crossy Road].” The only cost to the player in Crossy Road is to buy a new playable animal character for $0.99. Each adds charm and surprising interactions to the experience, going so far as to having “relationships” with each other the more you unlock.

Hall was never comfortable with games that force players to buy gems or coins to speed up a clock or allow passage after a spike in difficulty. Even Frogger, in its neophytian prescience, predicted the kind of “pay-to-win” mentality that exists in popular mobile games; back then, you had to spend a quarter to have another go. Hall wants to keep you playing, not keep you paying.

“As a parent, I feel totally comfortable buy[ing] this character for you,” he says, alluding to Skylanders’ influence on Crossy Road’s gamut of road-crossers. “You’re going to get at least three or four enjoyable hours out of it, and then it’s [still] there. You don’t have to worry about it being lost. You’re going to understand value.”

But why is the simple act of crossing a street so engaging? Why, when digital realms exist that transcend our own galaxy and take us on apocalyptic road-trips, is the road itself sometimes enough? Co-developer Andy Sum thinks its not just about the journey, but how long you’ve traveled.

“I wanted to make sure that the score remained really pure,” Sum says. He mentions a player just tweeted at him this morning with a score, comparable to steps taken, of over 1000. Sum’s own record is in the 500s. “Crossing a road itself … I’m not sure what’s too fun about that.”