How Roxanne Harris performs jazz with code

The middle child sandwiched between two brothers, Roxanne Harris first discovered her voice through video games. Those Super Smash Bros—99-stock battles that stretched for hours—weren't just sibling bonding. (I can attest to this!) They were Harris developing what she calls a parallel personality, one that existed as much in virtual space as physical reality. Some might have discovered this duality online, but games provided a perfect foil for exploring computer-mediated personality. "I kind of almost saw my personality in the virtual world before it fully developed," Harris says of those early gaming sessions in Queens.

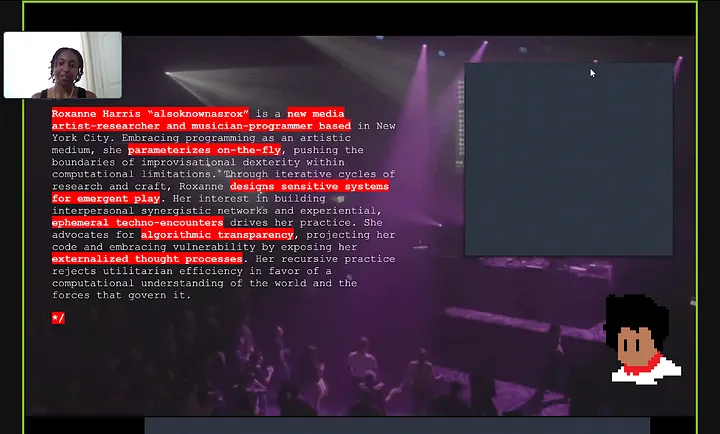

Now, the Yale-trained computer scientist and jazz saxophonist has found a way to merge those worlds through live coding, transforming lines of Ruby script into improvisational performances that blur the boundaries between musician, programmer, and instrument.

Growing up as the daughter of Jamaican immigrants, she initially dreamed of becoming a video game designer—not in the casual way every kid who plays games imagines making them, but with serious intent. She wanted to contribute to the complex ecosystems that required "many hands in many areas of expertise," from concept artists to sound designers. That multidisciplinary fascination would eventually lead her down an unexpected path.

Harris entered Yale as a computer science and mathematics major, coming off what she describes as a "pretty serious high school career" as an alto saxophonist. She was part of the first iteration of Jazz at Lincoln Center's high school academy, having played saxophone since second or third grade. At Yale, she initially kept these interests separate—parking her musical practice while focusing on the "career-heavy" quantitative disciplines. But something was not right.

"I was missing that creative aspect," she recalls. The turning point came during her junior year when she encountered the algorithmic composition tool Super Collider in a computer music class. This was her first exposure to scripting music, though still in an academic context—students would write compositions, run them, and submit them like traditional coding assignments. The idea of editing and manipulating code live, using it as performance material, hadn't yet occurred to her.

Then came quarantine. With her joint thesis proposal redirected (she'd wanted to combine computer science and music), Harris spent the summer diving deeper into computer music, eventually discovering live coding videos online. "The idea of editing and changing and melding the code live, using the code as material"—this was the revelation. For her senior thesis, she documented her learning process while building extension libraries for Sonic Pi, ultimately creating an EP of compositions that merged her technical and musical backgrounds.

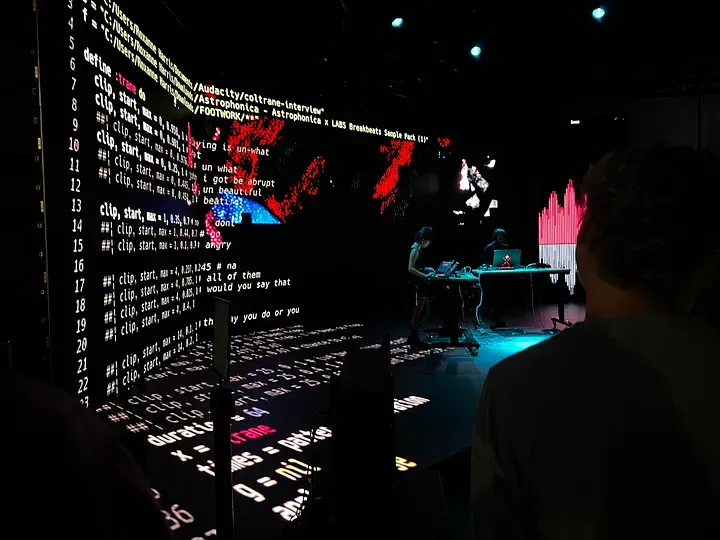

Live coding music has a longer history in algorithmic performance dating back to Brian Eno, but its incarnation as "algoraves" is a 21st-century invention. Live coding shows off the software to the audience while music and/or visuals are improvised. Harris's training provided an entry point for her creation in this context. "Saxophone in my head is like a stream of sound happening, very improvisational," she explains. "I feel like I translated that approach to my live coding practice." Where a pianist might manage ten different voices simultaneously, Harris imagines having ten saxophones, each improvising within a larger arrangement. The computer becomes her ensemble.

Before each show, she constructs what she calls a "playground"—a curated set of tools and functions, like “toys spread out in preschool.” These might include custom rhythm generators, algorithmic shuffling functions, or what she terms "deterministic randomness"—patterns that appear random to the audience but follow precise computational logic.

Initially, this improvisational piece was a bit hard to wrap around as a non-technical performance. I’m so accustomed to the idea that programmers do something independently, release it to the public, and then respond. But in live coding, that process is plastic and dialogic. Harris prepares, performs, and then adjusts the performance. The distance between what’s happening on-screen and what’s happening on Harris’ keyboard has collapsed entirely. “There are a couple of principal concerns,” she says. “But I spend a lot of time thinking about how to make myself comfortable onstage.”

And unlike posting her work to GitHub for posterity, much of what happens passes into memory. "I can't remember the last performance," she says, trying to recall anything pre-planned. "The vast majority of my performances are just completely improvised."

This approach reflects a more profound philosophy about human-computer collaboration. "We're computers too," Harris insists, comparing her practice to how she imagines John Coltrane's mind worked—generating complex patterns through internal algorithms. The live coding makes this process visible, stripping away the abstraction that typically separates audience from performer in electronic music. Unlike a DJ hidden behind a laptop or an electronic musician triggering pre-programmed sequences, Harris's screen projections reveal every moment of creative decision-making.

This transparency has two sides. Obscuring the process allows for secrecy, but it can also obscure brilliance. By showing the previously unviewable down cards, the “hole cam” allowed poker viewers to see the mind and strategy of world-class gambling minds. The DMC World DJ championships showcased the magic of turntablism and opened the door to seeing how DJs manipulate sound with technique. Harris points out that virtuosity is well understood in the live coding community as well.

On the other side, exposing your process is free soloing. "It's algorithmic vulnerability," she says, acknowledging the risks. “When there’s a syntax error, everything is going to stop.” Or worse, it just won’t feel right. The audience might think it's "the coolest thing ever" or dismiss it entirely, wondering why she doesn't just use FL Studio or Ableton. Some viewers, catching glimpses of familiar code structures, might even question the difficulty. But this transparency is precisely the point. Where traditional electronic music hardware abstracts functionality into buttons and knobs, Harris builds her instruments from scratch in real-time, showing the mathematical transformations that sculpt sound.

Practice session with music from Tyler, The Creator

The social dynamics of her performances fascinate her. At Wonderville, the Brooklyn arcade bar that serves as New York's live coding hub, she performs alongside vintage arcade cabinets—a fitting venue for someone whose artistic journey began with video games. I’ve spent some time at Wonderville and it’s absolutely overwhelming with every corner packed with games. But it’s the sensory overload that really captures Harris’ work an unholy fusions: games, music, and performance existing simultaneously, each medium informing the others.

Harris's setup varies but centers on Sonic Pi and Max/MSP, sometimes incorporating her saxophone for a "tangible somatic" element amid the digital abstractions. She thinks carefully about connectivity—how different software environments can communicate, how she can build bridges between platforms to use each for its strengths. This modular approach means she can show up to a session with just a laptop and build whatever backing tracks other musicians need on the fly. That flexibility is "something that in most contexts, you pretty much can't do," she notes.

Enjoy this profile? Consider supporting Killscreen for the year for more essays, interviews, and profiles on the future of interdisciplinary play.

The future Harris envisions pushes even further into real-time synthesis. She's experimenting with Unity, creating patches that let Sonic Pi control visual environments. The goal isn't just audiovisual performance but something approaching total improvisational control—music, visuals, and interactive elements all responding to her code in real-time, all vulnerable to the syntax errors and happy accidents that make each performance unique.

"At the end of the day, I want to make good music," Harris says. "This is just how I'm choosing to do it." But her choice represents something larger: a radical honesty about creative process, a willingness to compute in public, and a belief that code itself can be an expressive medium. In making her thinking visible, Harris doesn't just perform music—she performs the act of creation itself, inviting audiences into the usually hidden dialogue between human intention and machine logic.