Games are escapism, some say. They allow us to travel to far-off worlds, to forget our mundane existence tied down by rush hour traffic and routine trips to the market. With the advance of air travel as a safe and commonplace mode of transportation, companies like Spirit and Delta offer a literal escape: Pay your money, get on this humongous floating can of metal, and thou shalt be whisked far from here.

What used to be a single payment, though, has fragmented into an alarming confluence of charges and fees. Now, to fly away to your destination of choice, you not only pack your luggage but purchase the right to bring it along. You pay for the privilege of getting to where you want to go. Sound familiar?

With EA’s announcement early this year that all future titles will offer the potential for microtransactions, the world of big budget publishers has finally succumbed to the primary money-making gambit of smartphones and Facebook. Traditional platforms have made in-roads down this path before; whether it’s armor for your horse or a funky cap for your avatar, players have been able to spend small increments of money for additional features not already in the game.

The major difference was always initial investment: “freemium” phone games cost nothing up front, with the option to move through the game more easily with meager add-ons; full console or PC games will set you back fifty or sixty dollars, and players expect the whole experience unlocked from the start.

Such expectations have been whittled away over the past five years, with downloadable content offering new missions, characters or items becoming common-place, sometimes even released on launch day. Some players eagerly eat up the extra content. Many, however, are not amused, fearing an endless cycle of nickel-and-diming that interrupts immersion of play and ultimately empties their wallet.

Many, however, are not amused, fearing an endless cycle of nickel-and-diming that interrupts immersion of play and ultimately empties their wallet.

Lest they forget, this is a long held tradition in gaming: The Arcade was never a prix fixe meal but a pay-as-you-play buffet, with constant obstacles (“Continue?”) broken down with a dropped piece of silver.

But at home this was never so. Not too long ago, we bought a game for XX dollars and played what we found. Around that same time, a plane ticket nabbed you not only fast transit but innumerable, and expected, perks: free baggage, free meal, free pillows. These weren’t “free,” of course; the traveler already paid for them in the cost of a ticket. Just as a player would pay for all parts of a game in the initial investment.

With microtransactions and DLC fast becoming the norm, the future of gaming looks an awful lot like the present-day reality of long-distance travellers, asked to pay extra charges for previously included benefits.

Zynga’s newest entry to the endless runner genre, Running with Friends, uses Pamplona’s famous bull-avoidance festival as a cheeky and sensical setting. If you want to keep moving, though, you’ll need to pay coins, an in-game currency you buy with real money. By the time you’ve evaded a satisfying number of steers, you might have bought a ticket to Barcelona instead.

By the time you’ve evaded a satisfying number of steers, you might have bought a ticket to Barcelona instead.

At least the game is free up front. The real slippery slope, and the one airline companies like United and Delta are losing business over, is when your asking price is high to begin with.

Though EA CFO Blake Jorgensen back-tracked, saying his statement applied only to future mobile games, it’s not hard to imagine a time when every $60 retail title is but a starting point. EA’s own Dead Space 3 gives you an option to buy new weaponry using real money. Activision’s Call of Duty: Black Ops 2 introduced microtransactions to the popular shooter in the form of “Personalization Packs.” Most additions are cosmetic, but some unlock simple features with real utility — two bucks buys you an Extra Slots package that opens up ten new create-a-class slots. Sounds a lot like Delta’s Economy Comfort seats, which allow you more legroom for a price

Writer Alain de Botton spent a week living in London’s Heathrow airport. One of the more worrying aspects of his time there did not center on security, or rushing mobs of travelers, or the questionable hygiene of restaurant workers; his critical eye focused on Duty Free shops. There is “an incongruity between shopping and flying,” he writes, “connected in some sense to the desire to maintain dignity in the face of death.”

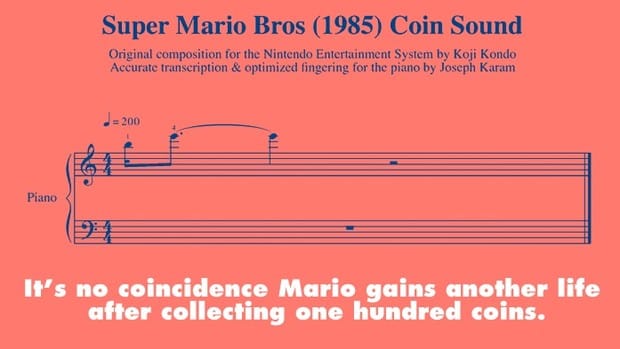

Even with today’s wall-to-wall safety measures in effect, air travelers instinctively acknowledge the chance, ever so slight, that this could be their last moment on Earth. Beyond the security gates of Heathrow’s Terminal 5 lay over one hundred stores, a higher density than the average mall, a place specifically created for buying stuff. An airport should be a place of transport, the argument goes, not another port of call for needless consuming. But we do so for that dopamine drip of the cash-register’s cha-ching. It’s no coincidence Mario gains another life after collecting one hundred coins.

Now the act of playing merges with a continuing need for commerce.

This taps into why microtransactions rub many so poorly. It takes what was once a playground and turns it into just another department store. Before the term “freemium,” you bought the game and played, pure and simple. Now the act of playing merges with a continuing need for commerce; the twain do not blend well.

The comparison doesn’t end with our ease at being nickel-and-dimed. Micheline Maynard, a writer for the New York Times, reported that almost half of all planes operated by major U.S. airlines are leased, not owned. This allows for more acquisitions at a flexible cost, providing for less financial risk to the operators with the caveat of less control. As digital downloads take the place of physical purchases, a growing percentage of our games are not wholly-owned by the players, but rather borrowed.

Buy a physical copy of God of War: Ascension and do with it what you want: play, sell, trade, lend. But download it over PlayStation Network and you are merely granted a license to play the software. From part one of Sony’s System Software License Agreement: “You do not have any ownership rights or interests in the System Software.” With the popularity of Steam and mobile platforms, along with next-gen consoles’ still cloudy philosophies on used games and online requirements, players may be forced to pay for access, in the form of subscriptions or activations that allow the very opportunity to play.

As the games industry turns more to services in an effort to nudge its way in front of our entertainment-devouring eyeballs, it’s no surprise the pricing model is shifting to reflect the realities of other service industries like air travel. And nobody knows exactly where we’re headed. Might the low-cost and hack-friendly Ouya be the JetBlue to PlayStation 4’s Concorde, whose super-fast (and super-expensive) planes were retired in 2003? Will a need for consistent broadband access to play certain Xbox One games mirror our insatiable need for fuel?

There’s a silver lining in all of this somewhere, as clouds are want to have. Unfortunately, it may be far from you, the traveler to distant worlds, but in the money-stuffed pockets of others.

Hero image via Kuster & Wildhaber Photography. Airplane photo via Olastuen. Arcade cabinet photo via StudioTempura.