Hurt You So

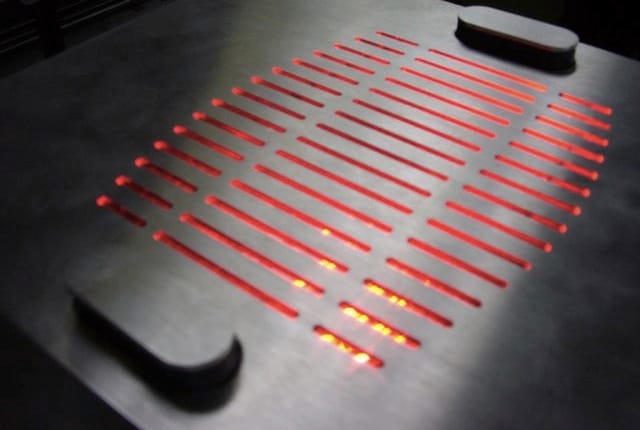

I place my hand on the Pain Execution Unit across two electrodes, the heel on one, fingertips on the other. Below my palm is a burning device and to the left is a small rubber whip. The whip looks like a bit of a joke. Earlier, while examining the Painstation, I’d pulled it out of its socket by mistake and had to hastily replace it.

Across the cabinet, my wife’s much smaller hand hovers above her own Pain Execution Unit. At the direction of the guy monitoring our play, we had both removed our wedding rings. To start the game we press down on the electrode buttons at the same time, as if we’re launching a nuclear missile. From now on, if we release the buttons, it’s game over.

/ / /

Painstation was created by Volker Morawe and Tilman Reiff of the artist collective //////////fur//// art entertainment interfaces. At heart, it’s a version of the classic table-style Pong cabinet, with the twist that when you miss the ball in this game, you get whipped, electrocuted, or burned. Or maybe all three if you’re lucky.

The edition my wife and I played is in the Computerspielemuseum in Berlin, Germany. That is, it’s inside a real-life videogame museum. The cabinet sits innocuously in a brightly lit and over-designed room full of old gaming machines like the Magnavox Odyssey, the Apple II, the Dreamcast.

Painstation is a bit of an odd addition to the place. It’s homemade; peripheral to mainstream videogame culture; and, oh yes, it injures you. But the for many of us who take a deeper-than-usual interest in videogames, Painstation is an iconic piece of game design and manufacture. The Painstation is infamous.

/ / /

Bip… Bip… Bip…

My wife and I twirl the dials controlling our paddles and bounce the ball back and forth. I’m reminded of how dull Pong is. Even though we’re wired up to be hurt in front of a growing audience of shuffling museum patrons, I feel fiercely bored. Fairly quickly I miss the ball on purpose, just to move things along.

A yellow icon appears behind my paddle and also behind my wife’s. The museum guy explains it’s a symbol for a particular form of pain—electrocution. Now, if we miss the ball and it passes over this symbol, we’ll get electrocuted. Every miss adds more of the symbols to both sides. We’re in this together.

Bip… Bip… Bip… In the spirit of science, I try to line up the ball to hit the electrocution symbol behind my paddle. It takes a while. I muse on the inanity of the activity. Playing to lose. Eventually I get what I was asking for.

Bzzzt.

More of a light buzz than a proper electrocution. Less painful than licking a 9V battery. Not that you should do that.

Bip… Bip… Bip…

Pong may well be the most abstract, most “pure” videogame out there. Plato would play Pong. On the other hand, it’s almost absurdly dull. It’s hard to engage with Pong in this day and age beyond indulging in light nostalgia. So bring on the pain.

It really is remarkable to have the chance to play with something that hurts you in a museum setting. To play Painstation, you have to notify the guy in charge of the museum, then answer his litany of questions: Are you pregnant? Use a pacemaker? Unusually low tolerance for pain? Finally, you have to sign a waiver form that he spookily removes from inside the Painstation cabinet.

The major idea behind Painstation is that it should lead us to care about our play again, “detrivialize” it. The artists behind the game have said they feel the system makes play more “realistic” and pushes it toward “real interaction” between players: not just signs and symbols on a screen, but electricity buzzing up your arm. The theory is that you don’t just have virtual agency as you bounce the ball on your paddle, but also a kind of real agency: if you make your opponent miss the ball, they get hurt. You, in a sense, have hurt them.

/ / /

Bip… Bzzzt… Bip…

Our experience becomes a kind of “pain tasting” experience. We’re interested to find out what each pain is like, not so much tolerating it as swilling it around our nervous systems like connoisseurs.

We’re playing Painstation at its lowest intensity setting—there are three—so the electrocution (yellow) is almost refreshing, like a chardonnay; and the burning (red) is a pleasantly warm merlot. But the whip (blue) is a problem. Remember this if you’re playing Painstation. Turns out that that stupid-looking whip fucking hurts. Think of choking down gasoline.

Not just signs and symbols on a screen, but electricity buzzing up your arm.

The first few times, it seems almost cute as it pops energetically out of its little slot in the side of the machine and whacks the back of my hand a few times. But then gets me a fourth time. A fifth time. A sixth time. I remark over the machine to my wife, “I do not want to be hit by the whip again.” She nods. The whip hits me again. “I really don’t want to be hit by the whip again.” Again, she agrees. And yet the whip, more than any other pain option, seemed destined for us. It hurts, and we laugh about it. You’ve got to laugh or you’d cry.

Bip… Bip… Whack whack whack whack whack…

/ / /

In Painstation, the standard play of Pong is altered via “power-ups” that are applied to the game with ever-increasing frequency. They raise the speed of the ball, make multiple balls appear at once, and much more. The result is that even a Pong champion wouldn’t be able to avoid having pain dished out. The gameplay swiftly moves beyond any semblance of a skillful activity toward a more-or-less constant stream of punishment.

What would be the point, really, of excelling at the Pong component of Painstation? The ball would ricochet off your paddle over and over, your opponent at the opposite end would be getting zapped, whipped, and burnt, and there you’d stand. Somehow not playing at all. And therein lies the contradiction. Despite their intention to create a game with consequences, you can very literally feel the artists’ conviction that if you’re not getting hurt, you’re not in the game. Painstation becomes a different game altogether, one played at the meta-level of physical tolerance.

In other words, forget Pong; it’s just the interface. The point is to stand there and take it. It’s play at the bleeding edge—no longer the nips of play theorist Johan Huizinga’s play-fighting dogs, but the whips of a machine made to hurt you.

/ / /

My wife and I play on bravely for a while longer, but the whippings only seem to intensify. At a certain point she can’t take it any more and pulls her hand off the electrodes. Her “Wimp-Out” meter drains away. I win!

Kind of. A truly massive welt runs all the way across the back her hand, an angry combination of the colors red and “bruise.” Distracted by staring at the whirling visuals of the game, neither of us had really bothered to check up on our actual physical condition. My hand was red, but hers was a truly horrible sight.

We walk shakily away, somehow a little angry about the whole experience. The museum is annoying. The Painstation is stupid and it hurts. My wife’s delicate hand has been mauled by the stupidly enthusiastic little whip.

/ / /

In this joint fury and licking of wounds might be the seed of what Painstation is really about. The artists cheerfully present the game as a reintroduction of the physical into the virtual, or as a way to create real consequences during play; but while that might seem intellectually accurate, it doesn’t feel that way.

Rather, the true message of the game is one of togetherness. You press your hands down on the electrodes in unison, the pain symbols always occur symmetrically, and the game is swiftly a blur of punishment on both sides. You play as one.

Painstation may not enhance a sense of agency during play—but it might just enhance relationships. Whether it’s drunk tough guys repeatedly punching each other to see who can “take it,” and then indulging in a manly embrace; or my wife and I suffering for our intellectual curiosity, being hurt together is one way of coming closer.

Photographs via //////////fur////