The Importance of Being in Jest

“Well, I never! Talk about bad taste!”

That line is uttered by an outraged woman in a golden ball gown. Onstage in the theater is a tenor dressed in an S.S. uniform, surrounded by several enthusiastic brown-shirted tap dancers with red Swastika bands on their arms. At this point in Mel Brooks’ The Producers the play Springtime for Hitler is enjoying its opening night. Offended patrons are filing out. Suddenly, a goofy, fatuous-looking Hitler appears onstage. His singing style and mannerisms are too outlandish to take seriously. His military decorations are bedazzling. The climate in the audience immediately changes from indignation to relief. Laughing—feeling as though they’re in on a joke—they sit down and enjoy the show.

Satire is a funny thing. Or, that is to say, it could be. It can be lighthearted and playful, focused on poking fun at social absurdities or idiosyncrasies (Horatian satire); or it can be acerbic, drawing attention to vice, corruption, hypocrisy, and immorality—typically that of people already in positions of authority or influence (Juvenalian satire).

There have been a few interesting, if relatively unknown, examples of satire in videogames. But part of our problem in identifying and interpreting satire may, generally, be the fault of games themselves. Comedy is notoriously tricky in videogames: Ron Gilbert once noted the difficulty in ensuring things like delivery and timing in an interactive medium. Concepts like irony, subversion, parody, and hyperbole have to somehow be conveyed through gameplay to mean much to the player. As a result, it seems that instead of becoming unified with design, satire is used—as in the Tentacle Bento fiasco—as a way to avoid rather than engage with criticism.

When games want to be critical, they usually aspire to be dramatic.

How do we know when something like Tentacle Bento isn’t satire, despite the exhortations of its fans and creator John Cadice? One aspect that distinguishes the card game—in which players take the role of a giant alien tentacle monster bent on sexually assaulting teenage girls—from satire is that it does not contain any discernible criticism of a vice or a foible. Instead, what it offers is a tongue-in-cheek homage to one particularly distasteful hentai trope—but this isn’t really about Tentacle Bento. This isn’t satire; it’s just exaggerated reference humor.

Satire is rarely discussed as an artistic aim in videogames, because we’re still fixated on representing evocative and earnest dramatic tensions. It has been done staggeringly poorly, and has been confounded or even ignored altogether by players one way or the other.

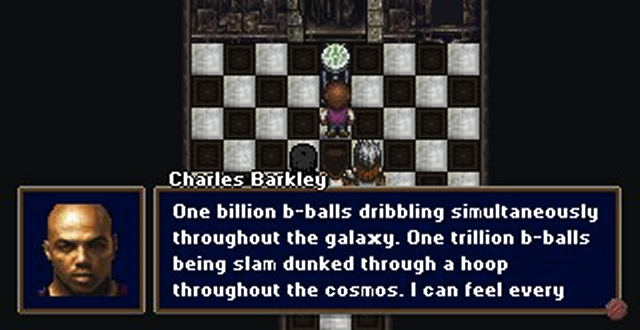

But satire has also been done well in videogames. The prime example in my mind is Tale of Games’ Barkley, Shut Up & Jam: Gaiden, Chapter 1 of the Hoopz Barkley SaGa. This game juxtaposes Western icons, figures, and concepts (mainly basketball) with a Japanese role-playing game design. On its face, the game is a tonally absurd sendup of Eastern and Western game-design conventions. But Barkley, Shut Up & Jam is also an ongoing discussion about cultural values. Each save point is represented by a truck pump that plagues the player with pages upon pages of forum screed, written in the voice of native Westerners that fetishize Japanese media (and what they perceive as Japanese culture). The beauty of these ludicrous text dumps is that a number are real—lifted from actual forum posts, their spelling and grammatical errors left intact.

What makes the satire in Shut Up & Jam so effective is that every enemy, every attack, every object, and every choice is subverted or exploited for the purposes of a recurring theme. Compare this with something like Ron Gilbert’s DeathSpank, which appears to be a sendup of an action RPG, parodying the genre’s overwrought gravity with overwhelmingly flippant writing. DeathSpank is firmly Horatian and may even be interpreted as a tongue-in-cheek love letter to the genre. Where DeathSpank falls flat is in its balancing of humor with gameplay. Genre conventions like fetch-questing may be questioned with a line of dialogue, but are never quite exaggerated or subverted. As a result, a lot of the jokes feel tacked on and do nothing to alleviate what amounts to a pacing problem deep in the design of the game.

Vidiot Game is a videogame’s shot at punk rock, espousing the Dadaist philosophy of poking fun at things we culturally value and understand already. The character-select screen includes different classes—but their stats don’t seem to matter. A magical genie asks me impossible-to-answer questions at intermittent points. Gameplay is comprised of simple, repetitive yet engrossingly odd mini-games, which may result in a completely useless victory. The screen flickers at an increasingly erratic rate the more I play. Vidiot Game possesses all the things I expect from a videogame: the illusion of agency, consequence, reward, a rule set—even glitches. But these are all designed to reinforce a kind of cosmic meaninglessness in the act of playing. The game eviscerates game conventions as a form of tyranny, and yet I’m the “Vidiot” who keeps coming back for a reward that doesn’t matter and a system that doesn’t really ever change.

Serious Sam is arguably a lighthearted lampoon of its more “serious” first-person shooter brethren. It ironically offers a game that is nothing but over-the-top, bellicose fun—but in the end, that’s all it is. While the “satire” in Serious Sam takes to task some formal and aesthetic mainstays of the genre, it doesn’t go on to say much else.

And that seems to comprise a lot of our problem when it comes to deciphering—and creating—a strong body of satirical games, which must unify gameplay and satire. Videogame culture continues to struggle with criticism and self-reflexivity, both of which tend to inform good satire. Games like Fat Princess, Eat Lead, and Serious Sam make use of satirical devices but don’t say much about videogame subculture or culture at large. Satire’s task is to raise a level of doubt or self-awareness in the player. But when games want to be critical, they usually aspire to be dramatic—as with Alan Wake or Heavy Rain.

No one in attendance at Springtime for Hitler, including the director, expected something so obliviously offensive to become a self-parody. The audience saw a horrible tyrant being depicted as an ostentatious buffoon, so that’s how they allowed themselves to be scandalized—because the broken taboo served the purpose of a humorous criticism.

What if, like that fictional audience, we perceive satire where there isn’t one? When we describe something like Tentacle Bento as satire, this is not a reason not to take its content or messages seriously—quite the opposite. We do not get to dismiss something problematic or incendiary as “just satire,” because satire is meant to question our failures and our errors, and unsettle and discomfit us out of our complacency—a place where we have dug a groove so profound we need help just to stand up.