The impossibility of Life is Strange’s conclusion

In its fifth episode, or roughly its fifteenth hour, Life is Strange reveals itself at last as what it’s covertly always been: a love story. This will come as no surprise to the attentive player. Dontnod Entertainment’s serialized adventure has intimated as much from the beginning. All the shared silences and affectionate looks, the nightly sleepovers and kisses on a dare: this is the stuff of romance. Max Caulfield, aspiring photographer and self-confessed high school hipster, is deeply enamored with her long-estranged friend Chloe Price—and vice versa. Life is Strange is simply the story of them coming to see it.

This journey is not without detours. And indeed, episode five, “Polarized,” opens with a fairly radical deviation: a turn toward the realm of basement lairs and imperious monologues, of murder mysteries and serpentine intrigue. Max has been drugged and kidnapped. Chloe has been shot in the head. The malefactor behind it all, meanwhile, turns out not to be petulant bully Nathan Prescott, as the game persuaded one to long presume, but rather Mark Jefferson, the seemingly benign photography teacher at Max and Nathan’s school. This revelation was the last-second twist that concluded the game’s previous installment. For six weeks we’ve thus been waiting for “Polarized” to pick up where the surprise ending left off.

the prophesized storm is a consequence of our hero’s time-meddling

What proceeds is the sort of confrontation between murderer and prospective murderee that ought to be familiar to fans of crime novels and police procedurals. Max sits restrained in steel chair in a bunker underground. Mr. Jefferson alludes ominously to the plans that lay beyond. He alludes to a great deal, actually. Now that he’s been outed as the villain, Mr. Jefferson is free to address the player with the grave theatricality of a TV serial killer, affecting a nice dulcet whisper as he holds forth on the subject of beauty in death—a pedagogue even in murder. At length Mr. Jefferson drones on. It’s all Max can do to sit back and endure the lecture.

Max of course has a distinct advantage over Jefferson’s former victims: with a bit of concentration she—and with the touch of the left trigger the player—can rewind time. And so with some effort Max manages to plunge backward through the sprawl of her captor’s nefarious machinations. (The challenge for the writers here was to furnish their heroine with a plausible escape route, and the one provided is rather elegant.) It’s none too soon. All told, this Jefferson business lasts twenty-five minutes—nearly a quarter of the episode, much too long to dawdle in the throes of genre-movie cliche. It’s therefore with some relief that the one finds Max returned swiftly thereafter to the brisker rhythms of time travel and the looming demise of Arcadia Bay.

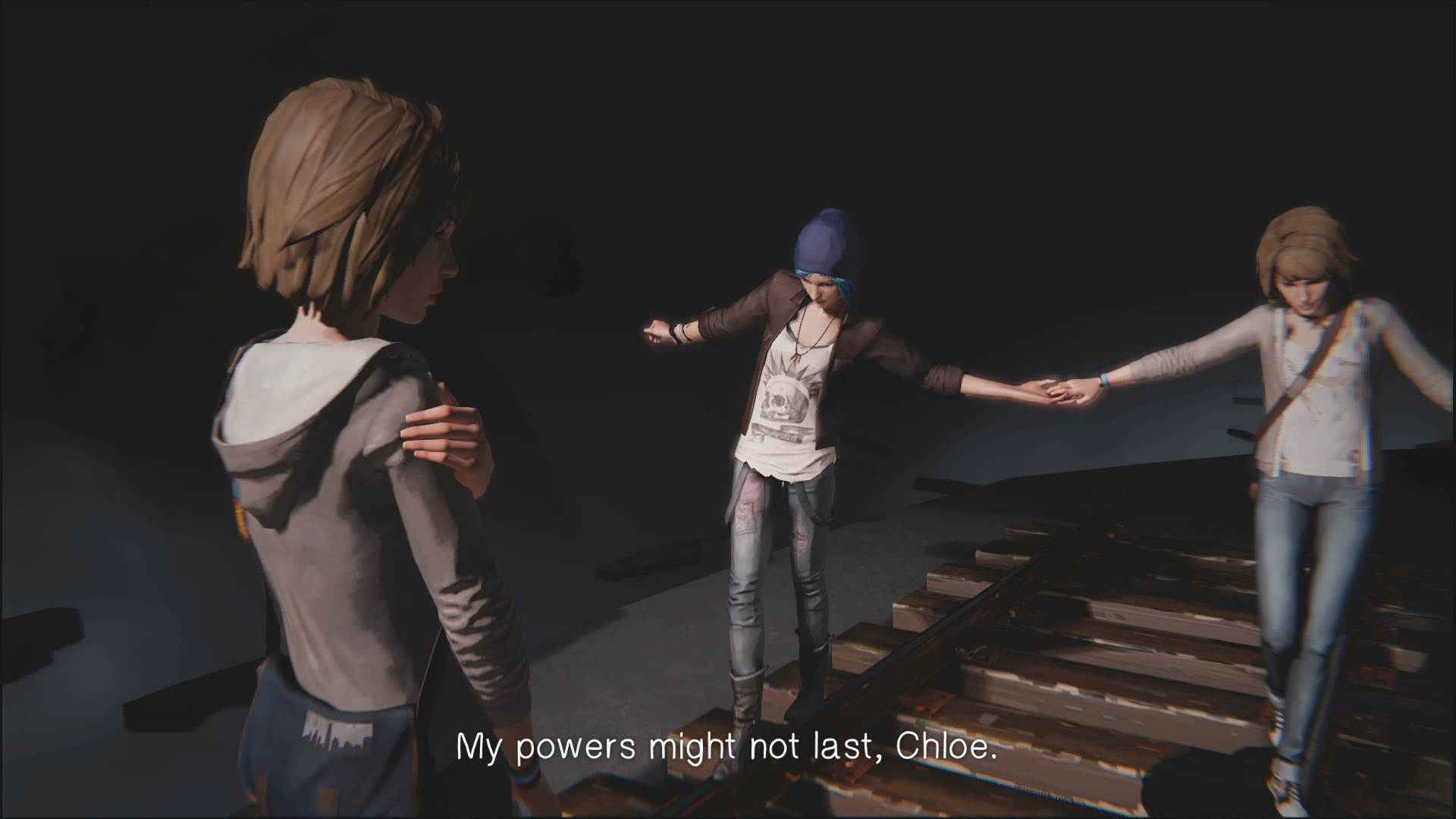

From the game’s beginning, the town has been in apparently cosmic peril, mere days away from doom wrought by squal and tornado. It’s been clear enough since episode one that the responsibility for this destruction is Max’s—Max, with her cosmic gifts. One gathers that the prophesized storm is a consequence of our hero’s time-meddling, the hurricane to her butterfly’s wings. So what’s to be done about it? Certainly the chronological hopscotching and leapfrogging of this episode’s second act isn’t helping any. Upon fleeing through an errant photograph from Mr. Jefferson’s deadly hideaway, Max finds herself ensnared in a thatch of alternate timelines, each stumbled into more calamitous than the last. Though for the player this stuttering romp is quite delightful: it’s the first occasion we’ve had to really indulge Max’s powers. The more drastic a leap through time seems, the more astonishing it is to experience.

The rigmarole culminates in a return, by way of a polaroid snapped toward the end of episode four, to the parking lot outside Blackwell Academy, where a pre-murder Chloe is set to march angrily into the Vortex party to meet her fateful end. And in the few seconds she has in the past Max must convince Chloe against it—to hole up with her alone, away from the threat of Mr. Jefferson, until Max can make it safely to the present. It’s at this point in the game that romance shimmers conspicuously into view. Chloe Price has been restored once more to life. Max is overwhelmed: overwhelmed by relief, by fear—and by love. The intensity of feeling in Max and Chloe’s reunion here is nothing short of extraordinary; indeed, it seems to me among the most moving things I’ve ever seen in a videogame. I can hardly overstate how fully the relationship has been realized: the grief in Max’s eyes as she recovers from the near-loss, the intensity and desperation in her voice as she pleads with Chloe to stay. The connection is resounding. It felt as true to me in this moment as relationships I’ve had for real.

an effort to remind players that Life is Strange is principally a game

The moment is over as quickly as it starts. Then we’re off again into the recesses of Max’s chrono-mad mind: a dream sequence whisks us along her subconscious, with opportune stops for gaming along the way. A dark jaunt through a labyrinth of interlocking dormitories is a riff on the hotel scene that winds up Silent Hill 2 (an audacious reference, and not an ineffective one); a reprise of the game’s introductory stroll through the halls of Blackwell, this time in reverse, nicely evokes Twin Peaks (a reference point cited many times throughout the game). And you may perhaps detect a bit of Arkham Knight’s first-person Joker finale in the maze-roaming set piece that caps this nightmare off.

“Polarized” is otherwise so linearly story-driven that the puzzle play of its dream sequence feels a little out of place. Or, less charitably, it feels like an effort to remind players that Life is Strange is principally a game: winding through the hallways of Max’s mind as spectral boogeymen with flashlights attempt to ferret you out is the sort of mechanical busywork you only do if you wish to assuage concerns about passivity. I suspect Dontnod is at least aware of the problem, even if they feel beholden to it. The only other time the integrity of Life of Strange seemed compromised for the sake of convention was when it contrived a pointless scavenger hunt for cans in the middle of its second episode. The cans resurface in the dream, scattered around for your collecting pleasure. “This again?” Max complains. (You’re welcome, mercifully, to leave the section without gathering any of them.) This sense of humor does much to alleviate the sense that the game is forestalling its own end.

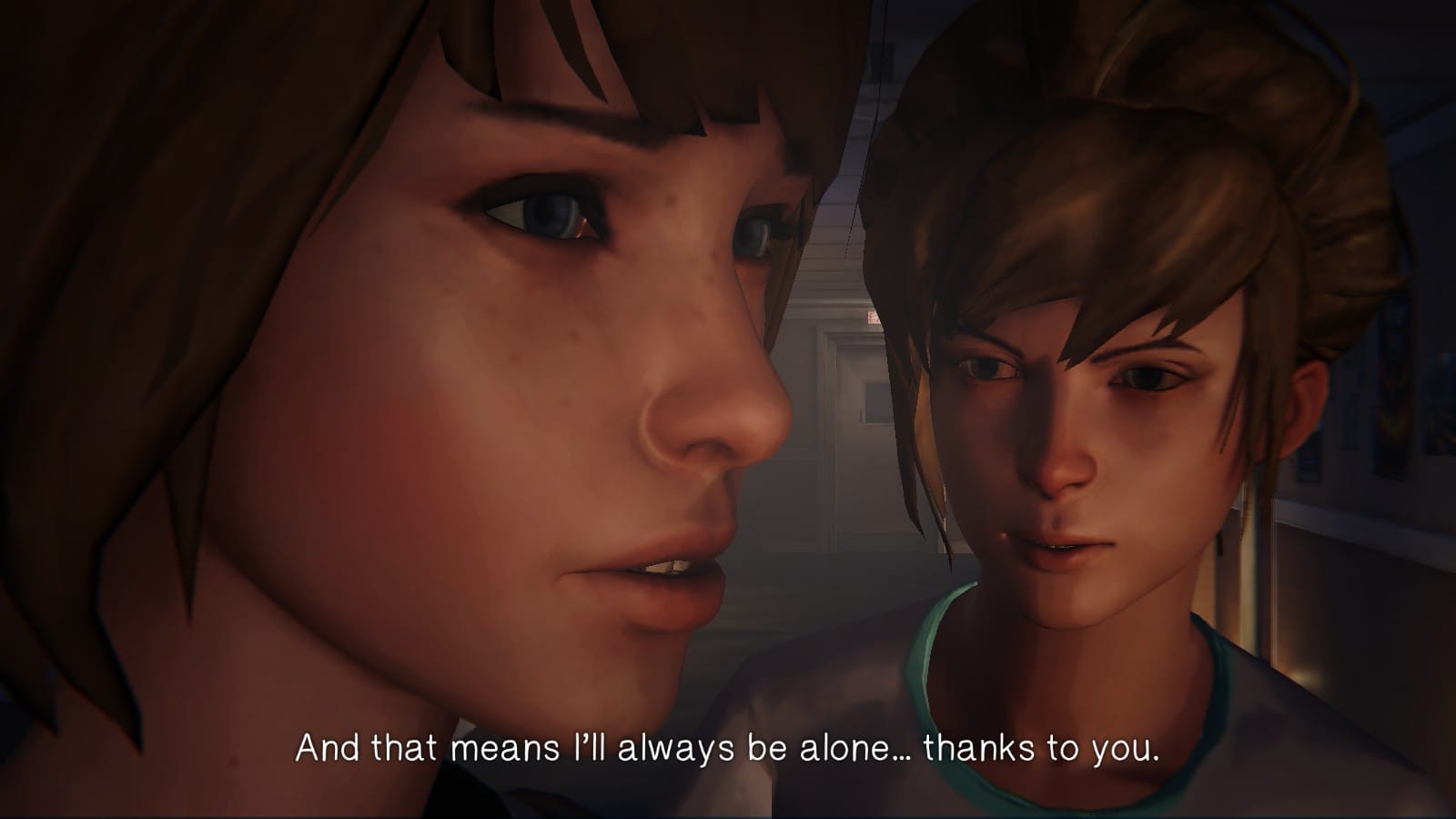

As a whole, the dream reflects the path Max has so far taken, with its curves and bends, its loops and meanderings. And what emerges in the path’s retracing is how central to it all Chloe has been. A kind of highlight reel reminds us of their time together, and its most momentous occasions, revisited in succession, begin to resemble a keen and impassioned—if mainly platonic—romance. I take it to mean that Max is apprehending her true feelings for Chloe as we are. Coming forth from her reverie, Max is brought back to the present and into Chloe’s arms, left to watch Arcadia Bay’s sudden obliteration. And then a final choice is yours to make.

Much has been made already of the ending of Life is Strange and in particular its unpleasant climax. You can do one of two things. You can return to the first juncture at which Max reversed time and stand by as Nathan Prescott shoots Chloe, thereby stopping the butterfly effect before it starts. Or you can accept the fate of your hometown at the hands of the storm and run away with Chloe safe and sound. What many players find objectionable, I gather, is that they want to save Chloe but feel it’s somehow unjustifiable to sacrifice the town. Or perhaps it’s that this choice commits the player to a certain moral ambiguity. In the cutscene that follows, Max and Chloe are found simply driving out of the ruined city in silence—not exactly what you’d call a satisfying denouement.

no less than love itself is the alternative

But for me the difficulty of this final choice, as well as the frustration provoked by either decision, expanded the game’s emotional richness. Over the course of its five episodes Life is Strange has been patiently establishing two irreconcilable arguments. The first is that Max loves Chloe. The second is that Chloe needs to die. Throughout the game Chloe has been repeatedly under threat, spared narrowly, even implausibly, by the time-shifting ingenuity of the young woman who most wants her alive. It takes a supernatural force to intervene time and again with destiny’s apparent design. But at what cost comes even well-intentioned interference?

What we were being trained to understand through the rigors of Chloe’s imperilment is that all of the attendant pain—all of this destruction, this chaos, this death wrought by the butterfly’s storm—is the price of Chloe living. (That surname is not incidental.) Thus the final choice is not whether Chloe ought to live or die. It’s whether you believe that Chloe living is worth it. How could any decision fail to be frustrating? Choosing Chloe is, in a sense, wrong—morally wrong, cosmically wrong. It’s supposed to be. What the game wants you to appreciate is how difficult it is be morally and cosmically right when no less than love itself is the alternative.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.