The impossible architecture of Castlevania: Symphony of the Night

This article is part of PS1 Week, a full week celebrating the original PlayStation. To see the other articles, go here.

///

Even in his early 20s, Giovanni Battista Piranesi could sense his dream of being an architect slipping like little drops of mercury through his nervous fingers. Eventually he would be given a single, small commission, the restoration of the Santa Maria del Priorato, but for the remainder of his time on the planet he was unable to secure work as an architect, so he fell back on an unprosperous career of architectural printmaking.

Some say this tormented him. It has been speculated—and speculation is all we have to go on since his autobiography was lost in England in the mid-1800s—that his most famous set of prints, “The Prisons,” or “Le Carceri d’Invenzione” (The Imaginary Prisons), were born out of a personal crisis: he was the most prolific architectural mind of his time, and no one would let him build a building. Others say the original idea for the 14 etchings, later expanded to 16, were conceived during a confused and apparently horrific fever dream. Whatever the case they were nightmares meticulously realized.

Whatever the case they were nightmares meticulously realized.

In Piranesi’s day, there really wasn’t an outlet for doing what he did with “The Prisons,” which is, to state things clearly, mapping out with a draftsman’s precision chaotic spaces that would require an astronomical budget to build and would probably collapse before they were completed. For this reason he can be thought of as a huge influence on many kinds of works of fantasy. Kafka, surrealism and Romantic poetry are often named. But I think also games.

In games, we find ourselves visiting unfeasible spaces on a regular basis. These are spaces not constrained by physical laws—the minarets in Monument Valley, for instance, built on euclidean geometry, or Fez’s cubes whose four sides somehow fall short of forming four-sided objects, or the floating megastructures of Destiny, which have a lineage to the colossal ships in Jodorowsky’s Dune. As the architecture critic Geoff Manaugh once told me, “Game designers have an exhilarating freedom to experiment with space.” In this regard, Piranesi was a major influence on game design, even if the majority of people making games don’t know it. And nowhere is this clearer than in Castlevania: Symphony of the Night.

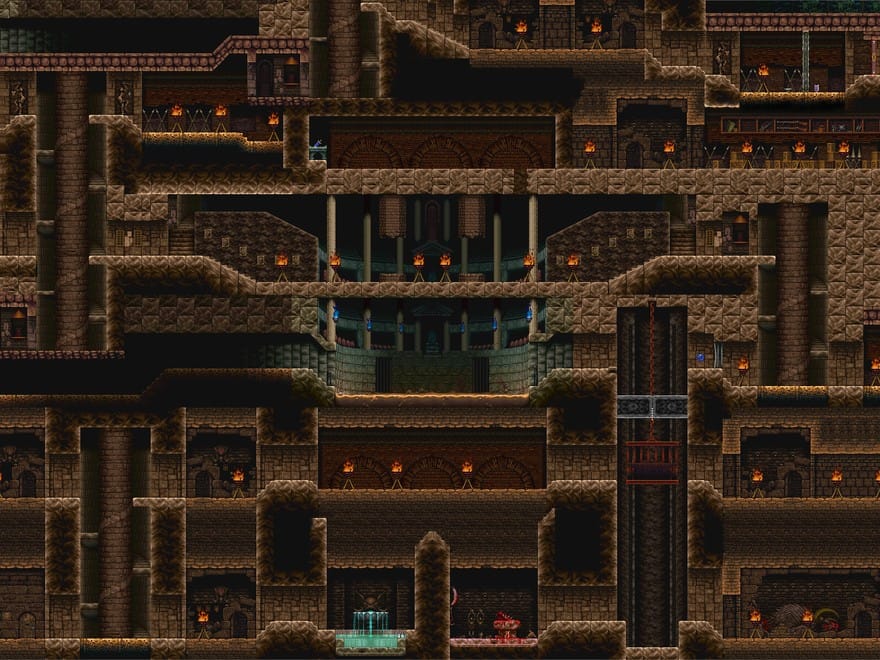

There are a lot of similarities between Piranesi’s metaphysical prisons, as they have been called, and the most celebrated and storied of the Castlevania games. Some of them are more superficial than others. “The Prisons” are often cited as a pivot point from the excesses of gothic architecture to the simpler neoclassical movement. Symphony of the Night, on the other hand, doesn’t look gothic or neoclassical. Rather it looks like the ideas of Gothic and Neoclassicism as repurposed for regrettable skull tattoos and Actual Pain tank tops. The castle is draped in a strange fabric of baroque mainstays and Roman pomp. This is not a complaint but a compliment to the artists. The art style feels contemporary and holds up great, just as “The Prisons” and its population of miserable inmates remain timeless after 250 years.

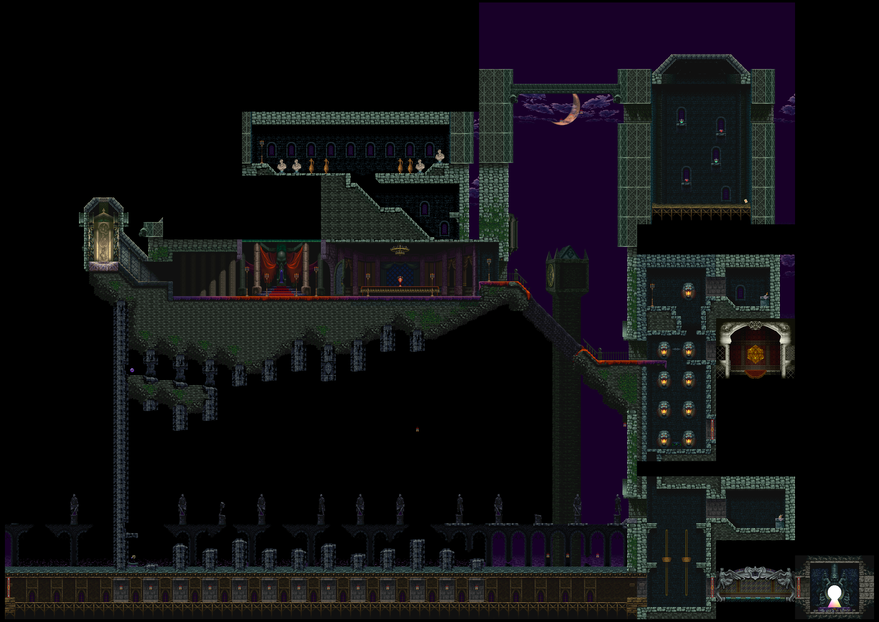

But more important than outward appearances is how Symphony of the Night captures the feeling you get when flipping through a book of Piranesi’s prints. This is the feeling of handling something that is too big to properly hold. The original size of the prints are 16 by 21 inches, and the layout of the castle is vast. It looks like this. (56K warning, if those still exist.) There is a pervading sense that these structures are too large for any conceivable use. The vaults in “The Prisons” have no ceiling and stretch on seemingly forever. Likewise, Dracula’s castle is immense, even for a castle of decadent scale. Not even vampires have time to leaf through a library with five stories’ worth of books. And what’s with all these stairwells?

And what’s with all these stairwells?

Another big intersection point is this: These are labyrinthine ruins that in no way could exist outside the stage they are depicted on. I am far from the first to point out that “The Prisons” are rickety structures that could not stand, but the same holds true for Castlevania’s house of the damned. As you jump and slash your way through the castle, you begin to notice unusual things. Why is it that decor like furniture and paintings is repeated over and over indefinitely, while things that should be symmetrical—say, the wings of the house—are not? The parapets stand in unnatural arrangements. There are towers where the castle lacks a necessary foundation, floating in midair. The entire architectural body is sitting on top of an underground river. The whole thing is suggestive of an architect gone mad.

The first suspect, obviously, is the man in charge. Symphony of the Night was created in 1997 under the direction of Koji Igarashi, a talented young designer with long, wavy, raven hair. Was Igarashi aware of Piranesi at the time? I doubt it. Last year, during an hour-long session at Game Developer Conference that I walked out of after ten minutes (I ended up watching it on GDC Vault for research), Igarashi revealed that the design of the castle was mostly pragmatic. Avid Japanese fans would buy games on the release date, beat them in a few hours, and sell them back to the game shop. This would eat into the company’s profits, since they only made money from selling new games. To combat this, he said, they decided to elongate the game with one huge level you traversed a number of times. This was not a tortured artist on stage, but a weary businessman.

To be fair, even tortured artists have to eat. In his later years, Piranesi used his talents to hawk antiques, illustrating catalogues that sold Roman urns and candelabras, items he had a vested interest in. But Piranesi obsessed over the Prisons throughout his life, coming back to them again and again, reworking them with a heavier hand, making them darker and denser, increasing the number of mysterious torture devices in the foreground. From the prints themselves you get the impression that they were not so much composed but unleashed during fits of nervousness, as hinted at by the hasty line work, which looks as if the etchings were scratched onto the metal in a kind of panic.

This is not true of Igarashi, his creation, his staff. If the man had an artistic vision, he has absolutely nothing to say about it and is taking it with him to his grave. Of course the castle was not the product of one man, but eight more of them, who are listed in the credits simply as designers. It’s impossible to say for sure how the castle was designed, but you can safely assume it was a collaboration of ideas, with one designer responsible for the map, another for the interior of the rooms, yet another for how you progressed through sections of the castle, and yet another for the monsters you found within. There is scant information on these individuals aside from their credits in other games. They were salarymen who left no trace.

So how then can we make sense of the disorder of the architecture in Symphony of the Night, this beast of a technical blueprint which overachieves at being a place to move through and takes on a twisted, surreal life? Maybe more credit is due to the castle itself. The requirement of housing a good game for the player to inhabit seems to have bent the structure and altered its shape. The castle survives in a form that you can halfway identify as a building, with ramparts and balconies and other castle-like things, but also as a well-oiled machine where there is always a foothold within jumping distance and a lantern to slash with a heart inside.

Some of the strangeness is due to the format itself. As one of the last truly great 2D games, Symphony of the Night arrived on the threshold of an era where anatomically correct structures were the new wave. The PlayStation, after all, was made to push polygons. The castle seems vaguely aware of this, aspiring to mimic a genuine place as much as it can. Like all those flat, side-scrolling worlds in games before it, however, it still scrapes by on the logic of cave paintings. There is no true north or south, no forced perspective with vanishing points; only up, down, left, and right.

The layout of “The Prisons” are equally hard to make sense of. It’s clear that Piranesi intended for them to be a one-to-one match with the ruins he saw in his head. Later in life, when he composed two additional etchings, he placed them in positions 2 and 5, instead of sticking them at the back where you think they’d fit. But in everyday use, as the art critic Philip Hofer points out, the prints were often removed from the book and hung on the wall in whatever arrangement the owner saw fit. The Prisons could exist in any direction, which was also the most unexpected turn in Symphony of the Night. After you had scratched and clawed your way through the game, apparently reaching the end, the designers flipped the entire castle upside down and had you play through it again. Then the real shit began.