In Defense of the 3D Platformer

Let me say it up front: the new Ratchet and Clank remake is magnificent. It also feels extremely strange, as though it hails from a parallel universe that isn’t quite our own. In this universe, the 3D platformer is ascendant. Good games are defined by everything it has in abundance: by the quality of their move upgrades; the length of their long jumps; the theming of their worlds; the cackling of their villains. Every game is legally required to have a fire level. Every game conveys the same set of values—duty, honor, the heroism of the ordinary, the sacrifice of the sidekick—beneath a surface of fart jokes and cartoon violence. Anthropomorphic mascots dominate the gaming industry and continue to exert outsize cultural influence, appearing in campaign ads and grocery store circulars; instead of a Carrie, a Miranda, a George, or a Kramer, people identify as “a Mario,” a Sonic, a Spyro, maybe a Jak. Banjo-Eightie has received universal acclaim. Super Mario Universe has broken new ground as the first MMO populated exclusively by Marios, scrambling around 3D levels of immeasurable texture and scale, many of which are shaped like Mario himself. We live in an age of unabashed totemism, and we receive a new Ratchet and Clank—bombastically orchestrated, aesthetically indulgent, functionally the same—with gratitude but no small measure of expectation. It is exactly what we wanted. It is the way of things.

I’m describing the universe I desperately wanted to live in and thought I would live in when I was a Nintendo 64-obsessed kid, polishing off Cloud Cuckooland—the last level of Banjo-Tooie—and dreaming of how videogames would evolve, having seen how they’d evolved already. Super Mario 128 was right around the corner, as I learned from rumors spread on the GameFAQs forums. I had no idea what it would be like. But with a distinctly childlike smugness I was confident that it would be more. It would have double the hats. Double the levels. At least double the graphics. And then Super Mario 256 would come along, doubling everything again.

We don’t live in that universe. It’s 2016, and the 3D platformer is no longer the pinnacle of game design I thought it was when I was 10 ; instead, the genre has been dead for over a decade. I’m not talking about 3D platforming as a basic mechanic, which lives on (in limited ways) all over the place. I’m talking about the 3D platformer as a discrete genre, with its hub worlds and iconic mascots and backflip upgrades and companion duos. The years between roughly 2002 and now are littered with evidence of its demise, and you can almost imagine a Wreck-It Ralph-like support group full of former mascots who have tried other careers since the bursting of an early 2000s bubble. Crash Bandicoot hasn’t been heard from since 2001; Jak and Daxter didn’t make it to PS3, bowing out in favor of Naughty Dog’s other—and decidedly more generic—creation, Uncharted. Spyro joined Skylanders, which is a bit like a C-suite executive becoming a door-to-door knife salesman. Sonic has descended into a pitiful spiral of narcissistic self-reinvention, like a less lovable Jenna Maroney. Banjo-Kazooie returned only in Nuts and Bolts, which might be the most depressing (and depressed) game of all time; I’ve never seen a genre hybrid more bitterly aware of the market need for it to be a genre hybrid.

The years between 2002 and now are littered with evidence of the 3D platformer’s demise

Mario continues his lone crusade, of course, kept alive by Nintendo’s panache and the sheer fact of being Mario, but a game like Super Mario 3D World (2013) is very different from a game like Super Mario 64 (1996): it’s the essence of a 2D platformer translated into 3D space, with none of the emphasis on exploration, topological intricacy, or collection for collection’s sake. Even Super Mario Galaxy (2007) was a step toward that model, and the new Ratchet and Clank is similar. Levels appear vast, complicated, and open in all directions, but within them you’re almost always funneled along linear paths, shooting endless enemies that come in shooter-like waves. Unlike other platformer series, Ratchet and Clank stayed alive throughout the 2000s and 2010s, continuing to iterate, greeting the future (hence Ratchet and Clank Future) with open arms. What kept it alive, however, is a canny instinct for adaptation, and a willingness—even in the first game—to diverge from the design philosophy that inspired it in the first place. You will jump a lot in this new Ratchet and Clank, as you did in the original Ratchet and Clank. But it’s still fundamentally a 3rd person shooter with “platformer elements.”

The sum of these stories is a larger story that feels pretty unique, all things considered. Videogames are an aggressively nostalgic medium, always looking backward before they look forward, yet something about the 3D platformer defies the cycle of reappropriation that makes old things new again. Other defunct genres are lovingly exhumed all the time, their mechanics—even if austere, even if unforgiving—mined for expressive potential we might not have recognized at the time: the isometric RPG in Pillars of Eternity; the roguelike in The Binding of Isaac; the FMV CD-ROM game in Her Story; the point-and-click adventure in countless indie reimaginings. In its old age, the 2D platformer has gone through an astonishing creative renaissance, its central mechanic—one of the oldest and purest things you can do in a game—becoming a vessel of pathos and philosophical rumination. Like novels, there are games of ideas. Many of those games are 2D platformers. Almost none are 3D.

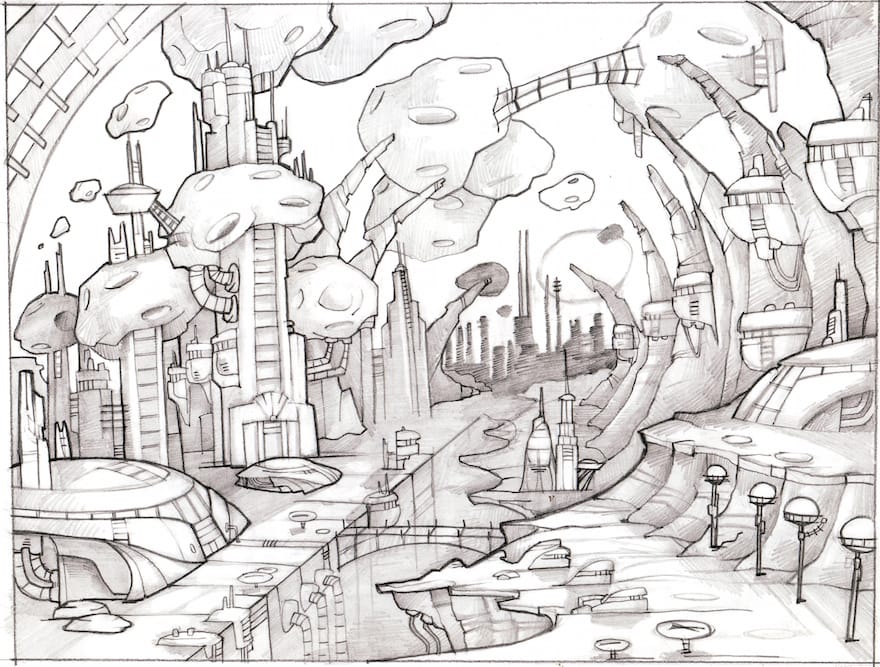

Concept art by Insomniac Games

To be sure, there are upcoming games, mostly Kickstarted, that advertise themselves as returns to the form: Yooka-Laylee and A Hat in Time, both spiritual successors to Banjo, as well as the notional Psychonauts 2. I don’t think I’m alone in feeling a rabid desire for everything they vow to bring back: vast worlds stuffed with a “plethora of delicious collectibles,” many of which possess googly eyes; bosses who “communicate via a collage of burp and fart noises”; a new generation of sublimely simple melodies by Grant Kirkhope (Banjo-Kazooie) and David Wise (Donkey Kong Country). But all of these are attempts at re-creation, driven to make again rather than make anew. In this way they are unlike the Ratchet remake in their attitude toward the source material; they want to preserve the genre in its sanctity rather than throw out the shit that feels dated. But they’re not dissimilar from the Ratchet remake in their overall orientation toward the genre’s pastness. Their explicit preservationism only underscores the idea that the genre is a relic of the past with no place in the present. It’s either an endangered species or something long since extinct—a dinosaur to be resurrected through careful DNA analysis.

If, as Darwin maintained, ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny, it’s hard not to see the 3D platformer through the lens of both—as an evolutionary predecessor and a form of infancy. On the one hand, it’s the ur-species behind every successive species of 3D action game. You can see its traces in everything: in the architectural intricacy and spoke-to-wheel level design of Dark Souls; in the endless collectables scattered across the map in Assassin’s Creed and other open-world games; in the basic grammar of moving the camera around with a second stick. Imagining Yooka-Laylee sharing digital shelf space with Uncharted 4, Dark Souls III, and Assassin’s Creed Whatever is sort of like imagining a primordial amphibian waddling into an ecosystem full of its descendants, all brandishing teeth and claws and complex eyes. On the other hand, the genre is attached to childhood, both aesthetically and conceptually. It’s the closest thing we’ve ever gotten to a playable cartoon, as the new Ratchet—a game based on a new movie based on the original game—makes abundantly clear. But it’s also about exploration and adventure within a distinctly constrained field of possibility: as confined yet limitless, as limitless in its confinement, as a LEGO set, a childhood bedroom, a theme park, a toy box.

In other words, it’s hard to take the 3D platformer seriously as a genre unto itself because it’s hard to see it as anything but a stepping-stone to other things. Its identity is enmeshed with a sense of becoming: games becoming bigger and better; children becoming adults; games maturing into genre specificity; humans maturing into the uncertainty of adulthood, where there is no abiding sense of finitude, no world-logic as neat and trim as the contours of Cloud Cuckooland, a place of insanity organized neatly—like so many platformer levels—around a central mountain hub. The 3D platformer is defined at every level by the possibility of completion. Adulthood is about incompleteness, as are many contemporary games: the endless grind of Destiny; the 18,446,744,073,709,551,616 planets of No Man’s Sky; the irresolvability of Her Story; the emotional paths of Firewatch, branching and intertwining. Childhood is about collection.

Its identity is enmeshed with a sense of becoming

I found myself collecting everything in the new Ratchet and Clank. Every gold bolt, every card, every weapon, every upgrade. I found myself in the familiar thrall of menu screens with precise, whole-number fractions: 1/3, 3/5, 28/28, 62%. I found myself returning to every planet systematically, “Map-O-Matic” in hand, to find nooks and crannies with crystals I had missed. Memories of Banjo-Kazooie came rushing back, memories of Kazooie squawking like a rusty see-saw as I ran him up treacherous slopes. In a return of one of my oldest habits, I staved off the final boss until I was satisfied I’d done everything else you could do. Beating him was like setting a capstone, ticking off a final checkbox. I returned to a way of approaching videogames in general that I’ve long since abandoned, as games themselves have increasingly traded the pleasures of delimitation for illusions of infinitude. I also ended up wondering if a return to collection is necessarily a return to childhood—whether it could be a form of escape that isn’t regression, a form of play that isn’t denial.

There are many circles in Ratchet and Clank. Levels are almost always circular in some way, their paths ending close to where you parked your ship. The game’s aesthetic is a chaotic retro-futurist assemblage of rounded spires, glass domes, and elevator tubes; every planet sort of looks like a cross between Tomorrowland and the Taj Mahal. The power of the PS4 is evident above all in the high-poly contours of things, now fully round where they were once jaggy. Things that aren’t circular are hexagonal—bolts, UI elements, segments on the weapon upgrade chart. Things that aren’t hexagonal are inevitably, somehow, circular. In a way, the whole game is circular in its return to the first Ratchet and Clank, even if it retains elements from later entries. And the genre to which it returns is infinitely circular, too: Spiral Mountain, Grunty’s Lair, Whomp’s Fortress, Tall Tall Mountain—all wheels within wheels, as though the ethos of the 3D platformer as a whole were a kind of circular self-containment.

image via the Blanton Museum

That circularity makes me think of the mandala as described by Carl Jung in Mandala Symbolism (1972)—the circles within circles drawn in sand by Tibetan monks; the circles one draws to stave off the chaos of reality, to feel a sense of centeredness, completion, totality. Mandala simply means “circle” in Sanskrit, but Jung sees it as an archetype of wholeness, a symbol of the self fully centered, appearing in the ancient texts of countless world cultures. Children are born with a seemingly innate desire to look at circles. But adults also, according to Jung, find an important kind of peace and pleasure in their shape–the “premonition of a centre of personality,” a vision of the self organized into a whole. He describes how drawing mandalas over and over again, tracing them, constitutes a therapeutic practice:

The severe pattern imposed by a circular image of this kind compensates the disorder and confusion of the psychic state—namely, through the construction of a central point to which everything is related, or by a concentric arrangement of the disordered multiplicity and of contradictory and irreconcilable elements. This is evidently an attempt at self healing on the part of Nature, which does not spring from conscious reflection but from an instinctive impulse.

An old teacher of mine once warned against the temptation to turn everything into “Jungian soup”; one of the things that makes archetypes archetypes is that it’s easy to see them everywhere. Nonetheless, I think it’s possible to see something mandala-like in the 3D platformer’s basic design, ethos, and rhythm: in the way it’s about nothing more than recursivity and completion; in the way it’s about tracing paths, filling in nooks and crannies, finding resolution at the top of the mountain. Playing a 2D platformer is inevitably about reaching an endpoint, even if—as in Metroid—you can move left, up, and down. Playing a 3D platformer is inevitably about reaching the center, even if—as in Ratchet and Clank—the emphasis is on shooting rather than platforming itself. With every collectable, you fill in a part of a predetermined tapestry; with every repeat traversal of the same concentric place, you add a grain of sand to something designed, something total.

Every time I talk to someone about Banjo-Kazooie, they speak of it as the vessel of a lost form of satisfaction. I always feel the same way. They remember how it brokered peace between warring siblings; they return to it later, at 26 or 32, to find comfort in its honeycombed finitude. They’re partly motivated by nostalgia, of course, a rose-colored attachment to the stuff of childhood. But I think they’re also motivated by a quality intrinsic and unique to the genre—a quality sort of lost when the genre died out, even if “100% completion” is still something you can achieve in games of various kinds; a quality we’ll hopefully get to experience again when we play the new generation of remakes, even if we see them through older eyes. I used to think of videogames themselves as a kind of ever-multiplying tesseract or Sierpinski triangle, one basic form multiplying itself with each successive sequel, the organization of the whole captured synecdochically by the structure of a single genre, a single game. That wasn’t how things worked even then; genre is an evolutionary tree, not a geometric shape, and in a lot of ways we’re lucky the 3D platformer branched off into other forms rather than fractalizing into infinity. But there’s value in the basicness of its shape, traced by the player in a therapeutic haze. I think it’s nothing less or more than the value of shapes themselves.