The new generation of arcades

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel.

Nostalgic arcade games offer larger-than-life experiences on big-screen TVs, encouraging new generations of gamers to come together and play. The clang of quarters dropping into Frogger (1981) or Tetris (1984) cabinets is a fleeing memory for many, but the joy of playing original arcade games like Pac-Man (1980), Donkey Kong (1981) and Space Invaders (1978) is far from dead. Instead, the combination of creative independent developers and technologies that easily bring these indie games to big-screen TVs is sparking an arcade game renaissance that’s spreading across living rooms and festivals around the world.

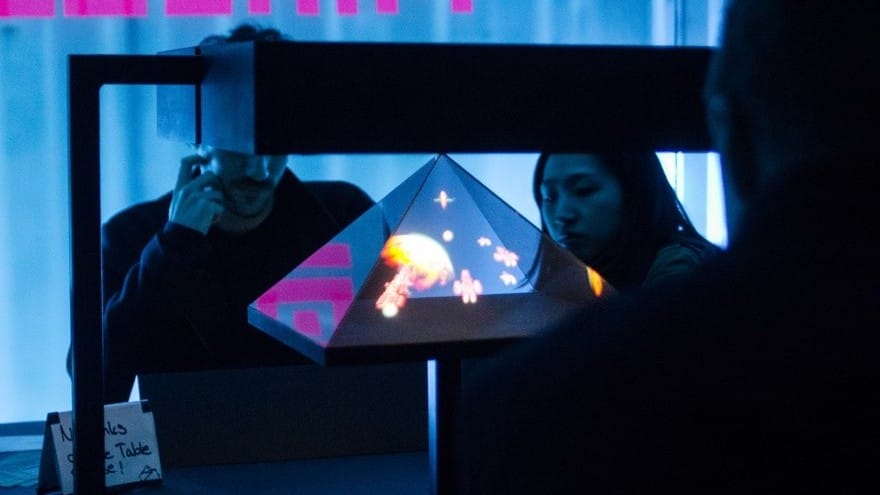

“A lot of people don’t know about indie games and the alternative scene,” said Thorsten Wiedemann, co-founder and artistic director of A MAZE Berlin. The yearly festival combines boisterous bar scenes with arthouse indie games, which are created by creative individuals or small teams often with very little budget. These gatherings often blend new games and technologies with a retro atmosphere that harkens back several decades when young people flocked to public arcade halls to play early digital videogames like Joust (1982) and Centipede (1980). This year, A MAZE Berlin took place over two days and nights in Friedrichshain, a district famous for its outdoor beer gardens, street artists and club scene. More than 1,200 young people flocked to the party celebrating a diverse and creative set of games.

A Maze Berlin 2016 by Jens Keiner

Unlike old arcade halls, games came to life on large TV and projection screens, illuminating throngs of street artists, painters, actors and musicians. At the event, Wiedemann used a variety of computers connected to 40-inch screens to build his exhibit. “I like to make the games bigger to turn it into that ‘wow!’ experience. You get excited when you walk through that door.” Wiedemann is part of a posse reinvigorating arcade culture. It’s something people enjoy sharing in public but also intimate places, like at home, where devices like the portable Intel Compute Stick can turn any HDMI-equipped TV into an arcade extravaganza. Off-the-wall game experiments also reign supreme in other parts of the world. Wiedmann’s friends at the gaming collective Babycastles regularly throw extravagant events in Manhattan. A couple of years ago, they projected Ms. Pac-Man across all four walls (and even the ceiling) of a room in the Museum of Modern Art.

Similarly, the London-based party organizers The Wild Rumpus bill themselves as “part arcade, part night club,” blending videogames with EDM-thumping raves. Ushering arcades into the millennial era, creativity and accessibility define this new kind of social gaming. But the true attraction of those old cabinet arcade days remains: to come together and play. From living rooms to bars, indie designers contribute to new arcade culture by creating mesmerizing visuals and alluring experiences that anyone can enjoy almost anywhere. Increasingly these indie developers are taking advantage of the increasingly simple and portable computer technology to bring back arcade experiences. Pocket-sized “mini-computers” like Intel’s second generation Compute Stick stream lightweight indie titles to big TV screens with an HDMI port. Gamers can now play arcade games once limited to old, bulky cabinets on large, high-definition screens at home, a friend’s house or a public gathering.

creativity and accessibility define this new kind of social gaming

According to the novelist Michael Kimball, who published the memoir Galaga with Boss Fight Books in 2014, arcades help establish a community and culture around gaming. “I grew up in a time in America when most people didn’t have access to videogames and then all of a sudden nearly everybody had access if they had a quarter,” Kimball said, remembering the birth of arcades in the late 1970s and early ‘80s. In the mid-2000s, independent game designers began carrying their wares to trade shows and galleries, and impromptu arcades began to spread. Traveling with a heavy cabinet game wasn’t easy. It often required a truck and a team of technicians to move and configure it. Aside from big screen TVs, new portable technologies removes much of the heavy lifting once required to set up an arcade.

Games like Circa Infinity (2015), originally developed for PCs and mobile phones, thrive on the big screen thanks to mind-melting aesthetics and mechanics. A deceptively simple game about navigating through endless circles, this interactable optical illusion captivates players and spectators alike. “Even if you don’t know what’s going on, the game is fun to watch,” said Kenny Sun, the one-man team behind Circa Infinity, explaining why its design attracts voyeurs as much as players. “It’s fun to figure out what’s going on since there’s so much visual stimulus.” Portability also allows Sun to easily take his game to festivals in Seattle, Portland, San Francisco and Austin.

A Maze Berlin 2016 by Jens Keiner

Mark Essen, one of the creators behind the classic couch co-operative game Nidhogg (2014), also saw the new arcade—from public events to house parties—as an opportunity while designing his most recent title, Flywrench (2015). “I wanted Flywrench to be the kind of approachable game that someone could watch you play and understand what you’re experiencing,” he said. As a result, the game builds on accessible mechanics similar to that of Flappy Bird (2013) or the freeware classic Helicopter Game (2004). “It’s very streamlined,” he said. “There’s no inventory. Nothing going on outside of what you see on the screen.” With the list of lightweight indie games growing by the day and designers gravitating toward more accessible and social experiences, the arcade of today appears to be more than just a resurrection. It’s a gaming metamorphosis.

Feature photo credit: Jens Keiner