Inquisitor is a hypertext engine that puts spatiality first

“I think games are uniquely suited to doing interesting things with spatiality, it doesn’t matter what form this takes—pure audio, pure text, pure 2D, pure 3D, or any combination of these, games are just really good at spaces.”

These are the words of Orihaus, a game maker who has made some of the interesting 3D spaces I’ve visited in recent years. Mostly, they are pitch-black alienscapes that writhe with elegant onyx architecture and an outright ominous aura. Games like the “dark striptease” of Obsolete (2012), the “constructivist megastructures” of Aeon, and the “virtual memory palace” of Xaxi (2013). But more recently, Orihaus has turned his attention towards interactive text, and it’s here that he’s expanding on his expression of virtual space in new, much vaster ways.

create impossible and paradoxical worlds

For his game To Burn in Memory (2015), which has you explore a city that never existed, Orihaus created his own interactive fiction engine called Inquisitor, which is “built around putting spaces at the core of hypertext work.” More specifically, Orihaus describes it as being a hybrid of Twine and Paradise—the former is perhaps the most accessible spatial hypertext game engine out there, the latter is more complex, built to create multiplayer worlds of text where players can create and become any object they wish. “The main thing I’ve taken from them is the non-linear world structure/navigation from Paradise, and the ease of use for larger projects from Twine,” he said.

Orihaus also noted that, due to Paradise’s influence, it’s possible for users to create impossible and paradoxical worlds, and also ones that are able to constantly reconfigure themselves so that a text-based roguelike is completely plausible with Inquisitor. This probably sounds a little confusing, and trying to explain how it all works can exacerbate that, which is something that Orihaus is currently tackling as he puts together a tutorial for Inquisitor. I gave the tutorial a go (in its unfinished state) and found it simple enough—once you grasp that a word can contain an entire world inside of it (made of other words and links)—with planets, cities, districts, buildings, whatever you wish—the basics fall into place pretty quickly.

What might be more surprising for people interested in making interactive fiction is that Inquisitor has no editor, “but that’s no issue since the worlds are just plain-text files and don’t require the user to write any code,” Orihaus said. The main tenet that development on Inquisitor follows is that it should allow for game makers to sit down and write with ease on any platform they wish. This is something Orihaus is trying to improve over Twine, whose little input windows he found awkward when working on large projects: “Honestly, I just wrote the engine to read the scripts raw, those I was writing to be converted to Twine.”

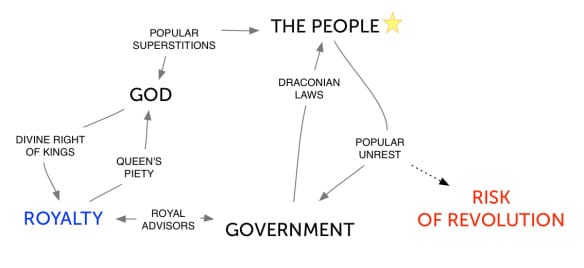

This is something he keeps in mind when adding new features, such as the “salience-based dialogue system” he’s currently working on implementing. The term for this type of dialogue system was coined by interactive fiction author Emily Short, which she describes as “narratives that pick a bit of content out of a large pool depending on which content element is judged to be most applicable at the moment.” While Orihaus was figuring out how to fit this kind of system into Inquisitor, he saw the diagram that Short drew below, and realized that it looked a lot like how his engine lays out world structure.

“And so taking a leaf from Paradise’s book, my implementation so far is to just have a miniature world inside a character’s head that you can navigate through dialogue options, keeping track of a bunch of basic tags that a writer can define (If ‘annoyance’ is too great they will just tell you to get lost or block off certain areas, but if ‘intimidation’ is higher then [they can] override that, for example),” Orihaus said.

He also has plans for a dynamic music system like those found in the later Myst games, “where you have a collection of individual ambient channels that fade in and out based on a number of variables.” But before that all that, Orihaus said that ease of use suggestions from other writers planning to to use the engine are his main priority. “Half the reason I’m putting the engine out there is that I love writers like Porpentine, and if this encourages even one new writer like her to express herself then it’s all worth it,” he said.

Currently, Orihaus is making a game called The Silver Masque using Inquisitor. You can get Inquisitor for yourself on Github. Check out the work-in-progress tutorial here. And follow Orihaus on Twitter for updates.