The insidious influence of blockbuster cinema on videogames

The idea of a “blockbuster” is a tricky one to pin down. The word itself originally referred to bombs used in World War II that were powerful enough to wipe out entire city blocks, and its metaphorical usage in that sense—talking about something that makes a significant impact on the population—was what most people had in mind a few decades later when it began to be used to describe runaway successes like Jaws and Star Wars. But since then, the word’s meaning has expanded even more to mean not just a major cinematic success, but also a movie made in the same style and tone as those successes.

The goal of a blockbuster is, simply, to overwhelm the viewer.

In the introduction to the 2003 essay anthology Movie Blockbusters, editor Julian Schnabel writes: “If ‘night’ is the key term structuring the discussion of film noir, the blockbuster appears most frequently understood through repeated association with an alternative key term—namely, ‘size.’ Size is the central notion through which the blockbuster’s generic identity comes to be identified.” In other words, “blockbuster” becomes all about attitude and scope, which is why Avatar and The Lone Ranger, despite receiving very different welcomes from the moviegoing public, can both be rightly classified as blockbusters. The goal of a blockbuster is, simply, to overwhelm the viewer. The concept isn’t about return on investment; it’s about the investment itself, about the size and scale with which filmmakers hope to dazzle the audience. There’s no such thing as too much.

Yet not all blockbusters are created equal. If the first modern blockbusters were able to pair size with focus, then today’s examples are victims of creeping bloat. The genre started out promising save-the-world stakes while also trotting nicely along through linear, cleanly managed plots: Raiders of the Lost Ark, Back to the Future, Ghostbusters.

Today’s blockbusters, though, are about size above all else. In place of a guiding directorial hand or vision—say, the kind of sensibility that could make something like Die Hard stand out from the pack—the films are subservient to the idea of overblown spectacle, and the filmmakers themselves are slaves to that whim. Think of the bludgeoning work of Zach Snyder, who broke out with the plastic, mindless spectacle of 300 and whose Man of Steel isn’t so much an action movie as a grim machine meant to pummel the viewer into submission. (The final half hour or so is almost nothing but CGI flying men knocking over CGI buildings with CGI tanks and ships, an orgiastic and totally numbing experience.) Michael Bay is the undisputed king of this kind of thing: he has made more than 10 hours just of Transformers movies, smashing giant metal blurs into each other at high speeds with no purpose or end in sight. And there’s the Marvel Cinematic Universe, each entry becoming more and more homogenized, devoted only to massive, choppily edited fight scenes strung together by thin characters and filler dialogue. I’m sure something happened in Iron Man 3, but I couldn’t tell you what it was.

Blockbusters are now all about delivering more: more music, more mayhem, more action, more characters, more sound, more explosions. They are altars to the god of sensory overload. Instead of captivating viewers by allowing them to witness action and vicariously feel suspense, blockbusters now seek to replicate that action impressionistically, thrusting the viewer into a hazy experience of what it might feel like to be in the film instead of just watching it.

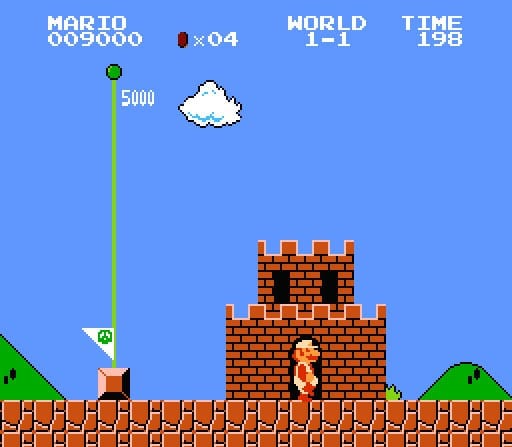

This, unsurprisingly, has led to some wildly varied movies, but it’s also done some interesting things to videogames, too, whose growth has roughly paralleled the development and expansion of the modern blockbuster. The adventure stories that heralded the birth of the modern home videogame—Super Mario Bros., The Legend of Zelda—were relatively straightforward action titles requiring the player to linearly progress the plot from A to B to C and so on, until things wrapped up. Super Mario Bros. was even literal about this: you can only move forward, not back. Once you cross the edge of the screen and begin to usher in the world beyond it, you cannot return to the place you left. There’s a pleasing emotional balance here with the blockbusters of the era: Kill the giant marshmallow man, save the princess.

Yet as blockbuster films began to become exercises in specific types of size and tone, videogames followed suit in their own way, offering an increasing number of tangents within games that replicated the multiple plotlines and feeling of space and size found on the big screen. For instance, a movie’s pacing is out of the hands of the viewer, so videogames couldn’t borrow anything like editing or special effects from cinematic blockbusters, but they could import the sense of leaving the viewer overstuffed. In blockbuster movies, you get tons of characters; in blockbuster games, you get tons of things for your character to do.

A movie wants to overwhelm you with images, but a game wants to overwhelm you with activity.

Blockbusters are all about size, which in film equates to visual scale and in games is often represented as “options.” A movie wants to overwhelm you with images, but a game wants to overwhelm you with activity: open-world environments, customizable avatars, side quests, collectibles, achievements, mini-games, and so on. Anything to keep you busy. You can spend as much time as you want playing checkers in Assassin’s Creed or casino games in Mass Effect 3. You can pass actual real-world days of your life just golfing or watching fake television shows in Grand Theft Auto V. You can ride your horse from one end of Red Dead Redemption to the other, doing nothing but shooting birds and collecting flowers and saving the same town again and again from a gang of thieves who never seem to get the message. You can, in other words, avoid plot and consequence as long as you’d like and just play around with the window dressing, which is exactly the same state of self-pleasing distraction that filmmakers want you to enter when you watch a robot that turns into a truck ride another robot that turns into a dinosaur.

The simulated “bigness” that takes root in the mind of the person playing the game is only one part of the picture, though. As the cineplex’s blockbusters start to run together narratively—often seeming to assemble stories and plots from pre-fabricated pieces, right down to the effects—so too do the games that fight for our time and attention start to feel interchangeable. Smart plotting so often feels like an afterthought in blockbuster movies because the films are constructed around major set pieces or fight scenes. It’s not that blockbuster movies can’t be well-written; rather, it’s that the writing is often at odds with the regularly meted out action scenes that got people into the theater in the first place.

Videogames have wound up following a similar path: smart humor, self-aware dialogue, and deep characterization abound, but all those things exist alongside button-mashing fights and quests for MacGuffins. They can whip from smart to dumb and back again so fast it can feel dizzying. Just as a big movie can bounce you from a great scene to a bumpy one, so too can games send you rocketing from a compelling confrontation to dry bits of exposition. Blockbuster gaming even takes movie dialogue problems to an extreme the movies themselves can never match by having the game’s supporting, non-playable characters repeat the same odd blurbs to the player over and over: play Skyrim long enough, and you won’t be able to go 10 minutes without hearing a sidekick complain again about “[taking] an arrow to the knee.” As a result, games can start to feel pasted together from a lot of little scenes that don’t necessarily connect or make sense together.

There’s something more insidious about the trend, though. Blockbuster movies have any number of quirks, but one of the weirdest is that their size (aesthetically and culturally) can make them feel like pop culture obligations. Avatar is the highest-grossing film of all time in the U.S., but most people would be hard-pressed to find someone who claimed it as their favorite film. Seeing it was just one of those experiences everyone wanted to have for a few weird weeks in 2009. It was lush and impressive, but also formulaic and a little laughable. It wasn’t that good, but it was big. That’s the greatest trick blockbusters ever pulled: convincing the world that they were fun and entertaining simply by virtue of being big and looking fun and entertaining.

As a result, videogames learned some of the wrong lessons of success. By overwhelming the player with sensation and choice and size, games can create the illusion of being a lot more fun than they actually might be. Some of this is confirmation bias—if you spend 30 or 60 or 100 hours doing something, and that something calls itself a “game,” you’re going to want to justify the investment—but it’s also because we’ve raised ourselves on years of movies whose size sometimes outstrips their entertainment value, so we feel comfortable repeating the process on our game consoles. A videogame like Dark Souls 2 is a perfect example of the way games have closed the gap between themselves and movie blockbusters: it offers epic quests built on a complicated mythology, it inspires serious devotion from its fans, and it’s mostly just exhausting. The point of the game is not to enjoy playing it but merely to say you made it through. It sprawls massively before us, bending our will to its own. It exists simply to exist.

That doesn’t mean all is lost, though, for movies or videogames. Size is not antithetical to brains or energy, and plenty of blockbusters live up to the size of their forebears while staying trim, smart, and entertaining. The best movie blockbusters are those that stay focused on the story at their core: Indy’s quest for the Ark, a young Kirk’s pursuit of Nero, the inexorable battle between Batman and the Joker. They keep their size in check, in a way. By the same token, the best videogame blockbusters are those that allow for excursion and choice but always connect those tangents back to the main story, and further, those games that push you gently but firmly along a path from origin to climax. Tomb Raider is a prime example of this type of game: big, action-driven, ably balancing key set pieces with exploration and options, but always making sure that the peripherals of the experience relate to the central narrative. Lara Croft shipwrecks with her friends and has to rescue them and escape, period. That’s the whole story. It’s a big game, but it never feels big. And that’s the paradoxical truth at the heart of all great blockbusters: to really go big, sometimes you have to think small.