It’s time for us to stop calling games "indie"

“It ain’t what they call you, it’s what you answer to.” ? W.C. Fields

In 2007, when I was a reporter at the Wall Street Journal, I (and most likely others) noticed something odd that was happening in the world of games. A crop of very small teams were starting to get much wider distribution and, ultimately, sales through digital platforms, albeit through an unlikely source: videogame consoles. The insurmountable obstacles surrounding commercial releases were suddenly being lowered and gamemakers like Jonathan Blow and the Behemoth started making serious bank, but in the guise of very personal and thinly assembled titles. These were magically called “indie games.”

My argument in the Journal was simply that the means of production that were enabling titles like Braid to exist and thrive were the same that fueled the New Hollywood movement that birthed Spielberg, Coppola, Lumet, Kubrick, and others. Microsoft and Sony were taking modest risks and dedicating marketing real estate to untested game makers who would then introduce new ideas to an otherwise samey and fatigued game-playing audience. “This [indie] gaming culture is launching its own stars who are both challenging the industry’s traditions and working with larger publishers,” I wrote back in 2008.

After the article was published, I received an email from two young (and recently married!) filmmakers named James Swirsky and Lisanne Pajot. We met at an early Kickstarter get-together and they followed up, stating that my article was a signpost for them as documentary filmmakers that a new “scene” that was emerging. A couple months later, they filmed me as a talking head for a small little title called Indie Game: The Movie.

Since then, there’s no doubt that “indie games” are a desirable asset in the world of game making. Pajot and Swirsky’s movie was a smash hit, titles like the Apple design award winner Badland touted “100% independent” in their credits, submissions for the Independent Games Festival and Indiecade ballooned, and multi-national corporations like Microsoft and Sony now vie for the strange title of BFF to the this game community (loosely defined), even allowing them onstage for their presentations at E3.

On the one hand, there is clearly something heady in the air in games these days. “Indie” is whispered as if an enchantment over crowd-funded projects, big and small, in hopes of another Double Fine Adventure moment. Prima facie, this is all clearly wonderful, and the influx of game makers from big studios to the stark blue ocean of self-sustainability will leave a lasting impact on the world of games. Whether this is a bubble, I cannot say, but there is certainly an excitement around the act of making new games. Given the new details that the average game designer is making less than $50,000, a sizeable segment of the profession is finally making good on both the “starving” and “artist” part of creativity’s past, present, and future.

On the other hand, this Cambrian explosion has spread the term woefully thin and it’s this current reality I’m interested in interrogating. I’m in as good a position as anyone to say this. And if you’ve been following Kill Screen you’ll note that this isn’t a “new” problem for us.

So let’s just say it. The term “indie game” no longer makes any sense. Let me explain why.

It’s impossible to define indie games.

In an earlier Game/Show, I explored this idea thoroughly. The biggest problem is that there’s no easy way to define what indie even means in a games context. To every potential categorization, there exists dozens of meaningful counters. When the winner of grand prize at the Independent Games Festival is unclear what indie means, it might be time to jump ship. Yet the term persists according to this faulty logic.

Indie means small teams:

Telltale has over 200 people. Valve has over 300. Both are “independently-owned.”

Indie means personal:

This perhaps comes the closest, but one asks, personal to whom? The player? The designer? The critic? And how personal? Autobiographical or just really, really deep, man?

Indie means non-commercial:

Microsoft sells enterprise software to Fortune 500 companies and Sony is so sprawling that its most successful unit is selling insurance. Yet both are vying to be the voice of indies. There’s nothing wrong with dealing with the big kids, but if slice your games up by corporate affiliation as some do, then signing with them and having your game featured on the front page is the exact opposite of anti-commerce.

Indie means raw and unpolished:

So I guess No Man’s Sky is out, eh? I mean, look at the damn thing.

Indie is a new phenomenon:

Spacewar! was a completely DIY effort in the 60s. And cue NYU’s Bennett Foddy who astutely pointed out:

Lemmings, a game made in 1991 by a self-funded team of 4, sold 15m copies—most at full price. Please stop saying indie games started in 2008

— Bennett (@bfod) May 23, 2014

Ok I think we’re done here.

The term has a useful history elsewhere, just not for games.

If Rolling Stone was the handmaiden of rock n’ roll, Pitchfork has defined independent music, and indie rock specifically, better than anyone else. And if you asked Mark Richardson, editor-in-chief at Pitchfork, what the quintessential indie band is, he’d tell you Built to Spill. I know this because I asked him.

Formed in 1992, the Boise-based Built to Spill scored a hit two years later with There’s Nothing Wrong With Love and were the darlings of the college alternative circuit. But then things got tricky. Faced with the demands of touring and personal life, lead singer Doug Martsch pushed the band to sign with Warner Brothers, one of the music industry’s “Big Four” and the diametric opposite to their former home Seattle’s Up Records. Martsch and Co. hired REM’s lawyer, who had ushered the Athens four-piece during a similar move to Warner, and carved out creative control for the band.

Martsch later admitted that there was something else motivating the decision: health insurance for him and his loved ones. “It was a hard decision to go with them—but it probably would have been harder if I wouldn’t have had a family,” he said in 1997. “If that was the case, and I was going to tour a lot and just work, then being on an independent label would have been fine.”

It’s hard to ignore the personal motivations for Martsch to make that transition and you’d have to be callous to fault him, but regardless, as a music critic, Richardson says, after signing to Warner, “No one would have said Built to Spill stopped being an indie rock band.” It’s an admittedly “slippery distinction,” but Richardson is pulling from a longer history of the medium that defines indie along both aesthetic and political dimensions.

By aesthetic, it’s a function of lineage. It’s about your sound but only in relation to references are. Richardson argues Mumford & Sons wouldn’t qualify as indie although they share a similar palette as the Decemberists. “If the band they’re channeling is Boston, they’re not going to be as indie. But if it’s Jonathan Richman and the Modern Lovers, that’s a different story.” This is, of course, splitting hairs, which is sort of the point. Richardson is outlining a particular point of view codified by his editorial institution. It’s what makes Pitchfork, well, Pitchfork.

On neither axis—aesthetic or political—do indie games, as currently widely conceived, share even a semblance of consistency.

By political, it’s more straightforward. The Big Four controlled distribution and college radio sprung up in the 80s to highlight acts that were off-the-radar. “The kind of music you’d call indie only existed on independent labels,” Richardson says. With few exceptions such as the Flaming Lips, the sound dictated the scale. That reality is echoed in other mediums like film and theater, where larger entrenched powers actively prevent the distribution of new and challenging work.

On neither axis—aesthetic or political—do indie games, as currently widely conceived, share even a semblance of consistency. They do not look the same; they do not act the same; and their designers don’t even share the same points of view. Per Richardson’s assessment, the lineage is all over the place ranging from huge traditional shooters to obscure, chippy leftovers.

Be honest. Fez is nothing like The Unfinished Swan is nothing like Among the Sleep is nothing like Star Citizen, yet all would fall under the moniker “indie.” At the very least, indie rock had guitars. Indie games, conversely, have nothing of the kind.

Politically, from the very beginning, videogames have had a strong commercial heritage, from their conception on equipment funded by DARPA through the console wars of the 90s to this year’s E3 that featured indie games on the showfloor. Moreover, games made by small teams were commercially successful almost immediately. They recamped during the videogame crash of 1983, but per Foddy’s point earlier about Lemmings, the suggestion that small teams making big things is new is preposterous. (If you want to know what a political framing of indie games could look like, see Paolo Pedercini’s talk from 2012. He’s clearly the only person who’s thought this through.)

By contrast, independent film, developed outside the studio system, didn’t apex until Steven Soderbergh’s Sex, Lies and Videotape in 1989. The New Hollywood movement was distinctly different from indie because it worked through traditional channels. Games have always had a blend of publisher-financed and self-distributed titles, lest we forget that shareware bought Doom creators John Romero and John Carmack matching red and yellow Ferraris. Atari was born of Nolan Bushnell’s boundless ambition.

Like it or not, indie in games cannot be divorced from indie elsewhere. In fact, the homage was almost required in an attempt to frame something that was apparently new (but really wasn’t). And chronically, game designers struggle to take creative or philosophical cues from anything other than other games. Indie has baggage; it has a weight, that must be reckoned, but without an accurate assessment of how other mediums have carved out space for the term, indie as a term, floats adrift, unmoored, and meaningless on the ocean of games.

Indie is best left to marketing, not criticism.

This year at the videogame convention E3, we heard something curious: “Well, if you’re gonna go indie, you gotta go full indie.”

Nevermind this idea that indie is something palpably quantifiable (70% indie vs. the full stack), whose temperature can be taken like Thanksgiving turkey and that the man uttering this ridiculous statement was wearing a t-shirt for The Order. No, the problem is simple.

Every week, we get emails from game designers pitching the same angle. Sam worked at a big development studio. He gets fed up with “the mainstream.” Sam quits his well-paying job. He’s going “indie.” The pitch is that indie is a magical shorthand for designers for “good,” which couldn’t be further from the truth. As a small business owner who made a similar transition from the Wall Street Journal, the narrative resonates with me, of course. But my sympathy ends there if only because Sam and I are no different from anyone else who wants to start something new. The incongruity is that “going indie” is regarded as some strange act of bravery; outside of games, it’s simply known as “making shit.”

And these press releases position indie as some discernible boundary between being and not being. And more often than not, it is something in direct juxtaposition to “the industry.” That’s the rationale fueling the no less than three different counter-E3 events we attended this year. But why whisper when everyone else is screaming? Especially when defining oneself simply by not being something else is imprecise, as designer Michael Brough was quick to note: “Really, it’s kind of paradoxical to talk about a scene defined by independence—how someone’s doing doesn’t have much direct bearing on how anyone else is.” Paradoxical, indeed.

And yet, admittedly, hawking indie as reflex has been useful for cutting through the noise. Or at least it was. On Steam, for example, there is an indie tab. It has indie games. That’s great. I check it out all the time. And then Steam released more games in the first five months of this year than in the entirety of 2013. Suddenly, that small curated space has become a catch-all.

But the cost is higher than just mindshare. If we continue to conflate all games made under the dubious conditions that define indie and place them in a single category, then we deny them the ability to be distinct works. Labeling cheapens the discipline by suggesting that somehow the motivations that separate Super Smash Brothers from BariBariBall, Metal Gear Solid from Superhot, Candy Crush Saga and Twodots, are somehow insurmountable. It gives those who group indie games as melodramatic platforms a convenient and approximate filtering system for ignoring anything in this massive expanse of games.

Games, of course, are not alone. Filmmakers struggle with the same problems of voice and the sole moniker “indie” carries a similar burden. “I worry that people click on the indie tab in iTunes and the audience actually needs help though,” Michael Raisler, executive producer for Beasts of the Southern Wild and creative director of Cinereach, told me. “They have a hard time finding stuff. I worry that audiences can’t find the content they fall in love with.”

“I tend to avoid ‘indie,’” Raisler says. “We make movies and we finance them. It’s independent, sure, but I don’t know what benefit we get.” If an Oscar-nominated producer worries that his films are lost to the noise and finds little use for the term, then how useful can “indie” possible be for games hoping to stand out on the infinite shores of digital distribution?

But the point is why do we, as critics and writers, actually care? If gamemakers find using indie helps them move more units, awesome. But we need not be bound by the same language.

New times demand new language

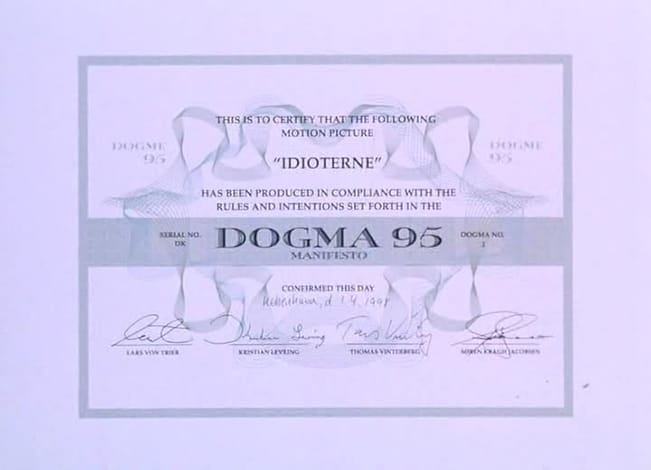

In 1995, two young Danish directors named Lars Von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg took the stage at Le cinéma vers son deuxième siècle, a celebration of film’s first century in Paris, and announced an audacious movement: Dogme 95. Taking inspiration from a François Truffaut’ 1954 essay in Cahiers du cinéma, Von Trier and Vinterberg issued a manifesto via tiny red pamphlets that were distributed to the audience. “In a business of extremely high budgets, we figured we should balance the dynamic as much as possible,” they later said. Dogme 95 was an experiment and attempt to simplify filmmaking and reduce it to it finest form.

It also had a lot of rules. Dogme films were always in color. No special lighting. Handheld cameras. No props. No murders. No credit for the director. Needless to say, Dogme is something more talked about than actually executed.

And in other disciplines, you find similar attempts to codify and outline something. Literature had the New Puritans; reporting had New Journalism; music is awash in micro-genres like witch-house and cloud-rap; UI is split between flat and skeumorphic, and modern art has microbially divided and subdivided too many times to list. But none of these shifts were just called “indie X.” It would be insufficient. The impulse, then, for gamemakers to want to participate in something bigger than themselves is totally reasonable. And that time came and now it has gone.

Earlier this year, we did a series called “The Future of Genre” as a first attempt at creating and cataloguing some of the myriad directions that contemporary games find themselves. Post-WASD. New Soulsian. Instant Death. As Clayton explained in the introduction, the problem with a binary approach (indie/not indie) is that “it focuses on games as objects of industry, and not of art.”

In the next decade, things are going to get really messy. New tools like Unity and new devices like the Oculus Rift are going to flood the game world with interlopers looking to dabble in interactivity. Local game scenes are likely to calcify. The gap between game scenes in New York and LA is already widening as the divide between those cities in architecture, music, design, photography, film, and just about everything else had previously. And older mediums like theatre, architecture, and animation are finally elbowing their way through the throng en route to ludic pastures.

But for each new entrant, there’s a little less room for some of the old heavies. The bus is getting crowded and it’s time to let some passengers off.

Good-bye indie. It’s been a good ride.

///