Keeping the Cold War quiet in CounterSpy

Videogames have been retreading the same old Cold War narrative since the existence of the actual USSR. Sure, they don’t always use the actual names of the countries or their leaders, but the true nature of most all of these red vs. blue conflicts is pretty obvious. Yet even now, when tensions between the US and Russia are higher than they have been in decades, the threat of nuclear warheads has more to do with the incompetency of silo operators than of foreign rockets making their way across oceans. The only way to make a new Cold War videogame story work in 2014 is either to reimagine the reality of the current situation or provide an alternate history of events past.

Dynamighty’s debut game, CounterSpy, opts for the latter, and manages to find an angle that hasn’t been done to death: that of the humanist third party. Where typically the videogame way is to fight for one side or the other (usually for the Americans), your goal in CounterSpy is to sabotage both sides equally until your rogue agency gains full control of both nuclear arsenals with intent to detonate them where they won’t hurt anyone. Of course your CounterSpy agent isn’t that strict of a humanist, since you’ll still manage to kill a couple hundred patrolmen along the way. Presumably it’s one of those “needs of the many…” kinds of deals, though the game never addresses the subject directly. Despite CounterSpy’s original-if-facile premise, the setup is effective enough to adequately set in motion the stealth action sequences to follow.

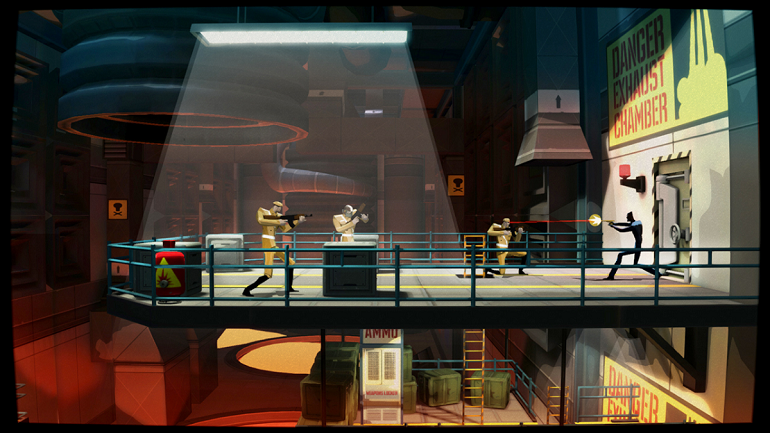

CounterSpy conveys most of what it is through style alone—a side-scrolling Cold War propaganda poster set to James Bond music. Angles are sharp and colors are bold, except where faded for vintage effect in menus. The player character is a shadow, save for his glowing white disks for eyes, cutting a sharp silhouette that either implies he’s using a lot of hair gel or he’s actually wearing some kind of retro-futuristic helmet, a la The Rocketeer. CounterSpy’s whole enterprise presents itself as leftover stage direction from Dr. Strangelove, minus the satire. But as well conceived and executed as CounterSpy’s visuals are, they can seem like a bit of a façade—a collection of influences that never quite bares its soul.

While visual flair is CounterSpy’s obvious standout characteristic, the game also offers a unique take on standard mission progression. One of CounterSpy’s core conceits is that the “Imperialists” and the “Socialists” are both using the same nuclear technology, so uncovering one side’s plans also effectively uncovers the other’s. Additionally, there’s a stealth meta-game represented by each superpower’s persistent DEFCON level, which rises depending on how much of a ruckus you make in-mission. CounterSpy’s environments are built of randomized sets of rooms, making each mission a bit different, even on retries. In fact, the game’s levels feel more like “runs” than discrete setpieces, the goal being to infiltrate the facility, grab as much as possible, and get out without alerting too many guards. You don’t repeat levels, you simply make a new run, which is a freeing notion especially for players who would otherwise be inclined to find everything in every level, even at their own peril. It’s a smart way to structure a stealth game, retaining a tightly looped arcade feel while still fitting the more prolonged way people play console games.

Yet certain hiccups in CounterSpy’s game design betray this balance. Like a dapper spy with a drinking problem, it’s much messier than its slick facade lets on. The only ways to lower the DEFCON level are to either pay a certain amount at the start of a mission to lower it one value or by holding up commanding officers. Basically, if you enter a mission at DEFCON 5, there’s a lot more room for error than if it was 2. I found myself stuck before the game’s final mission with both superpowers at DEFCON 1, forcing me to grind through regular missions to earn enough money and hold up enough officers to provide an adequate buffer. It’s at this point that CounterSpy asks for a lot of precision from the player that the game isn’t fully prepared to support.

It offers a smattering of stealth tools and actions, but strangely excludes other genre standbys that help maintain a sense of tidiness. You can’t move incapacitated bodies, meaning that there’s no way to meticulously clean out a room of more than 3 troops without engaging in a full-blown firefight. Additionally, if guards are alerted, you can’t simply hide until they lose interest because if left unattended they’ll radio to raise the DEFCON level and defeat the entire purpose of your repeat runs. When the stakes are low, the incongruity between CounterSpy’s stealth and action components matters little, but at DEFCON 1, you’re looking at mutual assured destruction. It’s a bit ironic that a game about escalating international tensions stumbles when it comes to its own escalating action.