Even for an episodic game, Kentucky Route Zero has had its own, peculiar sense of timing. Unhurried, seemingly without direction, but always apparently exactly where it needs to be whenever it finally gets there.

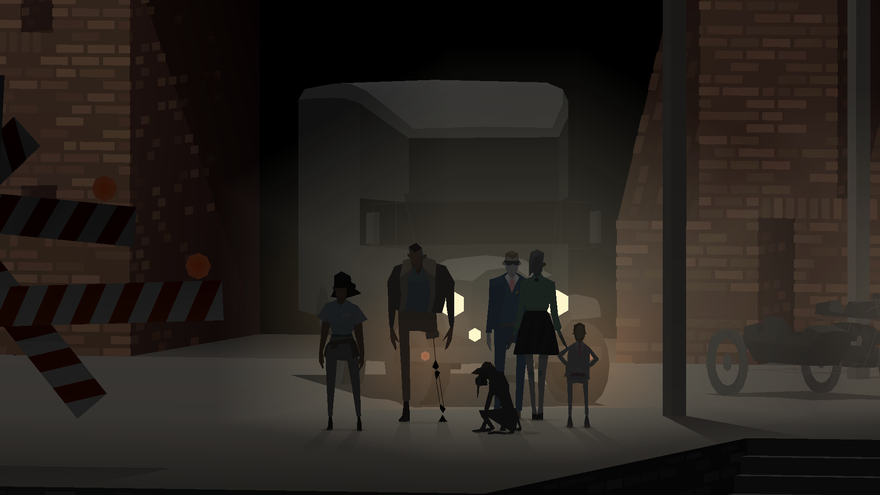

The game’s third Act, quietly released last Tuesday, eleven long, silent months after Act II, somehow both provides long-awaited rewards for those of us who have followed Conway’s meandering exploration of a gloriously impossible Kentucky back road, and actively resists any possible impulse to make up for lost time. Easily as long as the previous two acts combined, Act III stages its high point—a dreamy 80s-retro love song performed by two new characters in a seedy, nearly vacant dive bar—during the first third of its play time, and then slows down, asking Conway and Shannon to act as an incredibly unprepared tech support team, and sending the player through perhaps the most mundane text adventure game ever created.

It’s almost as if the long-delayed game were trying to put off its next interlude, staving off resolution to free itself from the responsibility of continuing—a situation familiar to Conway himself. His obligations to his past are increasingly entangled with the obligations of his companions, facing debts that cannot come due if the night never ends.

Within Kentucky Route Zero’s mythical, mutable world, bureaucracy and debt are often treated as the only stable points of reference. Places and people disappear. The same roads traveled differently lead to different destinations. Only debt is constant, building up little by little, day by day, a warm, friendly, steadying, unrelenting hand on your shoulder. When loved ones are gone, their debt remains, and even as Conway’s own body fails, he is reanimated by a payment plan, embodied in a glowing skeletal leg he cannot recognize as his own. It’s a striking image, given full resonance only when the player meets a factory full of neon, ghostly indentured workers.

As the game progresses, it becomes more apparent that the kaleidoscopic nature of the world is not just an aesthetic choice, a statement about human nature, but that mutability and debt are oppositional, mutually dependent strategies that characters and organizations employ to make sense of their world. While Conway and Shannon are looking for places and experiences not determined by their debts and the debts they have been left with, they also use debt, financial and otherwise, to preserve interpersonal connections. Conway carries his obligations to his employer Lysette—the final delivery for her antique shop which started and will ostensibly end the game—as a way to carry her with him as well. Neither the characters of Kentucky Route Zero nor their environments can be described by their debts, but debt functions as a point of contact, a thing that can be understood in a world that defies understanding. A stifling, constricting, oppressive, alienating thing, but measurable, durable, a tool everyone knows how to use.

Debt functions as a point of contact, a thing that can be understood in a world that defies understanding.

It’s exactly that recapitulation of the individual within the forms and structures of the body corporate that makes Kentucky Route Zero more than just an unequivocal critique of predatory capitalism. I’ve always found it easy to get outraged when reading about mining companies that would pay their workers in scrip, redeemable only in the company store, and never quite enough to pay the expenses of living in company-owned housing. It has, at least for me however, always been an abstract outrage, a thing of history books and museums, real but indirect, particular and removed. The combination of contemporary fiction and myth in Kentucky Route Zero allows it to engage history while escaping simulation. By following Conway’s shuffling footsteps (and directing them, such as Kentucky Route Zero allows), working to help him pay off old debts and taking on new ones despite his best efforts, I am implicated in his obligations. When Conway drinks the measure of whiskey that impresses him into a new, apparently inescapable thrall, I understand both his anger and his resignation.

We all of us owe someone something.

Jake Elliott and Tamas Kemenczy still owe me two more acts for Kentucky Route Zero. I’m not in any particular hurry, though. I’m happy to relish the connection for a little while longer. The timing isn’t right yet. We have a few more hours before dawn, and the debt cannot come due if the night never ends.