Lady of the Shard questions the role faith should play in our lives

Lady of the Shard is the latest webcomic from Gigi. D.G., the creator of anthropomorphic bunny comic Cucumber Quest. It’s about faith, starcrossed lovers, and the different ways in which the devout relate to the holy. Following the story of an unnamed space acolyte who lives on a floating temple in the middle of a distant solar system, it explores how her life changes as she discovers a burgeoning attraction to the Goddess she serves. Like many classic love stories, the two are kept apart by class divides, though in this case, they are less economic and more metaphysical. As they connect, the would-be couple uncovers not only each other’s pasts, but also that of an entire universe, revealing a story that uses the dynamics of relationships to question what role deities should play in the lives of their children.

Christianity comes in many forms, some more forgiving than others. While some sects might weigh a person’s good deeds against their sins to see whether or not they are worthy of God’s love, others simply require that all a follower do is believe and repent. I was raised in the second camp. At first, it seemed a comforting prospect, the idea that I didn’t have to earn salvation. But with grace comes guilt.

I was taught that I was inherently sinful. That I, as well as anyone else who ever has or ever will live, did not and would never deserve God’s love. That we were evil and nothing, and without God’s pity, hell was our natural state of being. I was taught that if I wanted to survive, I needed to prostrate myself before him. The success of myself or my family meant little compared to the words I recited nightly to an omnipotent being who apparently still needed the comfort of a child to feel secure. In my church, praise was all we ever existed for, and to have pride in oneself was to go against our purpose. I was sold the image of a loving creator, but I found myself in debt for the crime of being born.

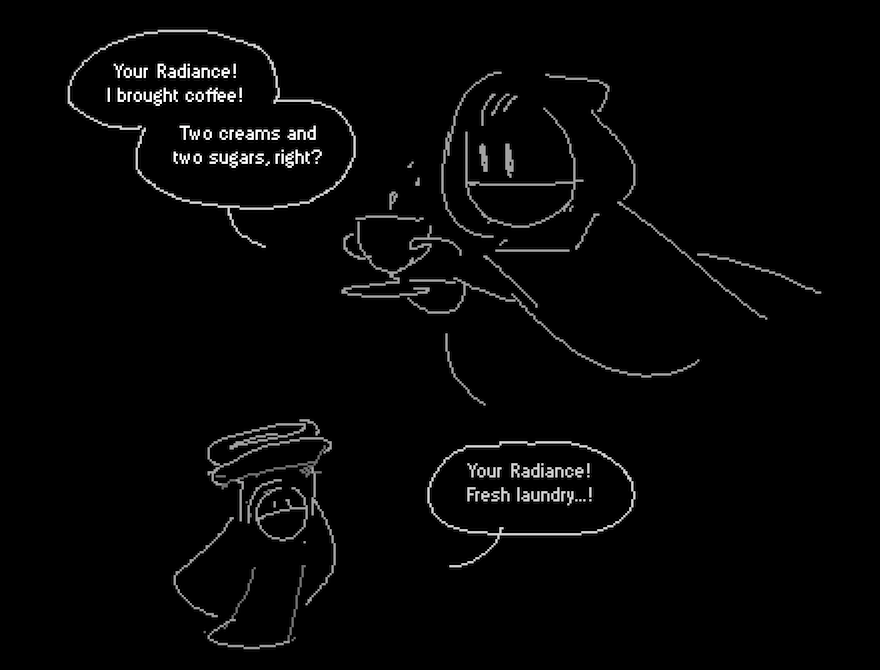

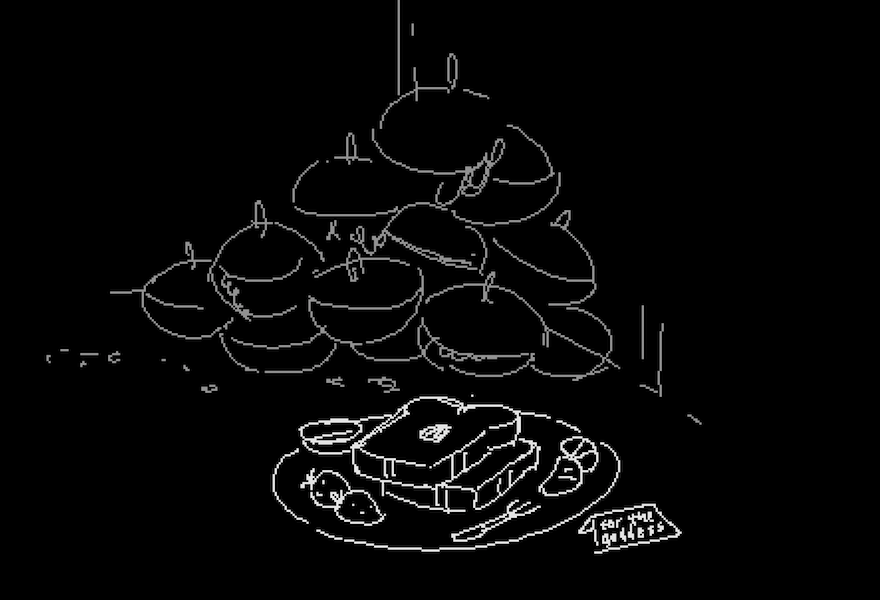

As Lady of the Shard begins, this is the situation our acolyte finds herself in. Her life is one of rituals and obedience, and her little quirks of individuality are punished by her peers. She is afraid to take credit for her work, and constantly plays down her importance in light of her duty and her superiors. She is devout—more so than most—but because her faith manifests itself in an unfamiliar way, she is a misfit. While others see their Goddess as more of an idea or a social custom, she truly loves her, taking the devotion she was taught to an almost romantic level. The problem is that she treats her beloved like a fellow human being, ditching traditional reverence to show her the same kindness and familiarity she would extend to anyone else she liked. In other words, if everyone else leaves the Goddess treasure for their daily offerings, she leaves her pancakes.

I was sold the image of a loving creator, but I found myself in debt

I have never met someone who doesn’t like pancakes. This goes for the Goddess, as well. After a few instances of otherworldly intervention, it becomes apparent that the acolyte, despite her oddities, is favored. The high priestesses hem and haw, before offering her a chance to clean a long-forgotten sacred chamber. In her enthusiasm, she accidentally bumps into an ancient bell, and within a few a short panels, her Goddess heeds her call and joins her in physical form.

What follows is a long-dive into the history of the universe the comic takes place in, complete with twists and turns and battles with other deities. Continuing the trend set forth in the beginning, this is largely done through the lens of relationships, as our acolyte explores different positions of powers in her flirtations with various Gods and even other mortals. Some are healthy, others are abusive. All are, for their divinity, recognizably flawed.

What stuck out to me most, however, were the conversations shared by the acolyte and her Goddess early into their meeting. As the acolyte bows to her and declares her lack of worth, the Goddess tells her to rise. In a comforting voice, she explains that the reason she became interested in the acolyte in the first place was because of how she would speak to her in her prayers like an equal. She would ask her about her concerns, and take into account feelings that others considered the Goddess to be far above. While the acolyte still considered herself lesser than her Goddess, it was her willingness to empathize with her that drew her in. The Goddess almost seems mournful over how small the church has made the acolyte feel.

The two begin to talk about the distant stars, technological metropolises that have wavered in their faith due to their prosperity.

“Is it really OK for the people you rescued to stop paying tribute to you? Isn’t it ungrateful?” asks the Acolyte.

Her Goddess responds.

“A goddess does not demand tribute, Acolyte. If the refugees no longer need me, they are likely enjoying an age of peace. Do you not consider this a good thing?”

This is unconditional love

This selfless giving is entirely different from the type of God I was taught to worship. In a brief moment of contemplation alone, the Goddess wonders about her place in the universe. It is not that she dislikes offerings—everyone enjoys a little recognition now and then—but she concludes that she is better than needing them. She applauds seeing her children independent and prosperous, happy just to see them grow. “The Distant Stars may do as they like,” she declares.

This is unconditional love. It has its risks and its sadness, and as the comic plays out, the Goddess must contend with them. However, in her power, she feels they are well worth taking. It’s the type of sacrifice a parent offers their child, as they leave home and forget to call. It hurts, but there is also pride to be found in their success.

As the comic progresses, it moves beyond the temple as the acolyte and Goddess explore both an atheist society, as well as a society ruled by a different Goddess who demands subservience from her people and constantly reminds them that they are nothing. But despite making strong claims about the dangers of faith as manipulation, Lady of the Shard doesn’t outright condemn any of these cultures. Rather, it explores the types of relationship they offer, and the happiness that follows when those involved care less about power dynamics and more about bringing out the best in each other.

You can read Lady of the Shard over on Gigi D.G.’s itch.io. To see updates on her work, follow her on Twitter.