Artist, jeweler, metalsmith, and art conservator Lauren Eckert shows us what it means to look at craftsmanship through a contemporary lens. Drawing from inspiration from the objects in video games, religious iconography, and classic science fiction VFX, Lauren’s work gives metals and jewelry a life on screen—and similarly, digital objects a physical life. Whether through wearable pieces or digital triptychs, Lauren’s projects make a space where past and future, alchemy and technology, collide.

We speak here about the magical process of anodizing metals, the material culture of the video games she grew up with, and her role as budding art conservator.

How did you come to the material culture of games as a medium?

I had been into science fiction in the arts for a long time. When I was little, my first video gaming console was the Gameboy Advance. I would play Pokémon and Zelda. I was really into horror movies, for a while, I still am really at heart. I liked all the special effects that John Carpenter would use—silicone, plastics, tiny models. Those were materials we were working on in school. I liked horror movies with real special effects.

I went to Tyler School of Art, and there’s a strong CAD-CAM program there. I liked how technology-focused the program was. They had a substantial 3D printing lab. That shiny technology was beautiful to me because. I went to school, and I got really into 3D printing and technology. I also learned how to work with metal and different plastics and the art form. Small sculptures were really attractive to me because I could use almost any material I wanted. I went to Peter’s School of Craft. I learned more about the historical background of craft. From there, I’ve just been more interacting with content for the contemporary craft field at large, which has led me to where I am today; my work in art conservation.

Tell me a little about your first experiences with metal and jewelry and bringing that into the virtual space, and vice versa.

My professor would 3D print these forms for his jewelry because you could not make them by hand. That was the appeal of 3D printing, in small sculpture and jewelry: you could make things that were so complicated because the computer would do all the work for you. You just have to tell it what to do. You could still use digital tools and have the presence of your artistic style in hand with that. What sold me was we 3D printing wax and then casting it with traditional metal casting equipment. Molten metal becoming something that I saw on a computer was so cool. That sealed the deal for me.

What is the importance of the physical process of anodizing?

Anodizing is when you run an electrical current through titanium, and it creates the chemical reaction creates an oxide layer on the metal, which is a bright color, depending on how much electricity you run through it. It’s a process that you can use to make your materials colorful. I had been doing these illustrations, and I’d taken inspiration from these saturated colors. I jumped at the opportunity to use it in my 3D work.

Sometimes, it can be difficult to get like metal see a lot of different colors. Sometimes you have to use patinas that are strong chemicals. It can be hazardous from a studio perspective if you’re doing it a lot. You don’t want to expose yourself to all these different chemicals all the time. With the anodizing process, you don’t need any crazy chemicals. From a studio safety perspective, anodizing was helpful. It’s really easy to replicate it with the same consistency because it’s a scientific process, so you can standardize all the different elements so that you can make the same thing over and over again. You have like a little power box—an anodizing machine that provides electricity. Then you put your piece in water so that the water will carry the electricity evenly over the entire surface. The part that I’m touching gets colored is connected to the power source. When you touch the metal, it completes the circuit. When I remove my hand, that’s when it stops because the circuit is no longer completed. The anodizing process goes through a whole spectrum of colors because the oxide layer becomes thicker and thicker, refracting light in different ways. So if you stop at any point in the process, that’s the color you’ll get.

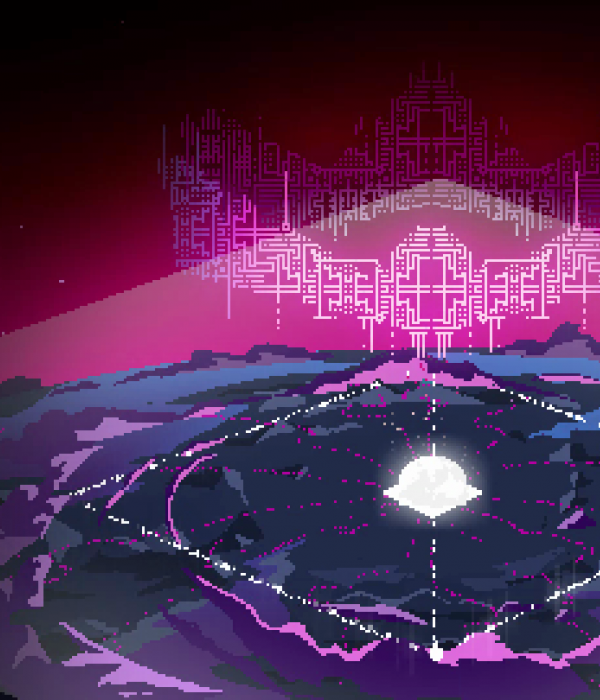

The Planes of Mystic and Material Memories is a digital collage. How does a piece like this get interpreted into metalwork and jewelry?

I was looking at a lot of medieval art and stained glass. I am a big fan of Hieronymus Bosch, so I wanted to make a triptych. I also wanted to use it as an opportunity to do some world-building. I wanted there to be a lot of density of information. The middle panel is this gateway, it has these keys, and then there’s an actual arch. The three-pronged object is a reference to a dowsing rod, a divination tool that people would use to find water sources. The middle panel is about searching and finding this gateway to this dimension where I’m doing all my world-building. I’m imagining all my objects in my body of work, all coming from this strange, timeless dimension. That’s the middle panel, and then the left and the right panels are the different facets of this world. The left panel has more natural imagery; creatures, the mystic plane. The right panel has more material things like objects and gems and bottles of vessels and candles. That’s the more tangible side of this world. The mystic and the material are two sides of the same coin. They’re opposites, but they go together, especially if you’re thinking about something magical like alchemy.

We typically think of craft as not a screen-based medium. When you were first working with jewelry and technology, did you get any pushback?

That perspective does exist in the field where it’s like, Okay, well, this is like a traditional medium based in the tangible. All these technological things are taking away from the tradition of the medium. I don’t think it has to be a dichotomy; there can be a little bit of both to make something greater than the sum of its parts.

Can we talk about the origins of your piece, Synthetic Relic?

I’m still using the computer to make these types of objects. I will lay out all my metal fabrication on a 2D plane so that when I cut and saw it all out, it’s easier for me to fabricate. But so the process starts digitally but ends up being tangible in the end. Conceptually, I was thinking about how pendulums are a divination tool and the magical side of it. I was thinking about something that you might arrive at during some journey. The illustrations on the piece are celestial. I was thinking about that otherworldly dimension. The claw references the medieval fantasy world. I use anodizing for it to make the different colors. I’m trying to connect my like, tangible, like fabricated metal pieces, to my more virtual illustrations taking inspiration from this 8-bit style.

I called the whole series synthetic relic because I wanted it to be like something a little bit from the past. And then which is like the relic part, and then something a little bit from the future. So a lot of my work, looking to imagined futures from different science fictions. Imagining these futures like that action is happening in the past. And then I was also thinking about, as an art conservator, how we carry the past into the future.

That connects to my other pieces in that these pieces all come from this world where it’s a little bit, it’s a little bit timeless. My work is like a time portal. The objects I make I hope are something you would like to arrive at and maybe be like an event in a story. I imagine somebody taking it off like a wall—maybe that causes something to happen, like Indiana Jones when he takes the thing off the pedestal and then all of a sudden, the temple starts to collapse.

There’s been a deeper interest amongst game designers in the use of 8-bit. And some of that’s a function of games that people grew up with. What does the pixel represent for you?

I was attracted to it because of the nostalgia. Because the information is dense with pixels, that is concise. It allowed me to make these little symbols that I like to use. I like how hieroglyphics would work, how you can communicate a lot of information. I have a maximalist approach to color. So I was trying to carry that over to my metal. The density of information works when you’re trying to make something out of fabrication because then you don’t have to try and make it.

Game makers are often creating digital objects, and they want those digital objects to have a tactility. For folks making video games right now, do you think they’re actively thinking about objects in this anthropological way? These objects in the game have inherent meaning. And they’re not necessarily constrained by the real, so this meaning exists in real-world objects to like people have, like sentimental attachments to objects.

In Pokémon, the Pokéball everywhere because it’s what catches the Pokemon. Sometimes these objects also function as symbols. Objects carry meaning, and so the object can function as a shorthand; it communicates a lot without words. That is why things become very popular for a franchise or a game. It means more than just the images, the colors, the pixels.

You’re studying to be an art conservator. How are you finding that balance between like, conservation, which is a past-facing practice, and with the work you currently deal with regarding looking at speculative futures?

In the actual day-to-day, my artwork is the processes are technical and scientific. That anodizing process was scientific because you have to do all the, you have to make sure you’re anodizing bath is the same. Art conservators have to know a lot of chemistry so that the day-to-day is really similar between my art practice and then becoming an art conservator learning all the science. Conceptually and thematically, art conservators are researching the past. The purpose of all that is to make the object last into the future; you’re trying to make these objects last longer than you’re participating in something that isn’t so immediate in the past and the future. So you’re doing all this work for the future. That relates to my art practice of thinking about the future from the point of the past as well.

I’m acutely aware that physical objects will live on past whatever happens with ZBrush, Rhino, or any digital programs. A huge issue in digital conservation, where so much of it’s tied to these commercially available tools. There is something beautiful about thinking about creating something either digital or physical that will live on past our lives? That’s what I like about science fiction is you’re thinking about the future. The current moment can seem immediate sometimes. When you think about all these traditions, you’re thinking about the past. It makes you a part of something greater than your current moment.

Some of your work references stained glass. What interests you about religious, spiritual, and alchemical research and motifs?

Stained glass is inherently beautiful. I like all the religious themes that people use to use glass; one way people use stained glass in churches is when the light comes through, it is like heavenly references. It makes visible people’s connection with God because it uses the light to make it more ethereal and illuminates these stories. I’m attracted to the rich storytelling that people use stained glass and all the imagery. Religious art is appealing to me because people would make religious art and be patrons of religious art because they wanted to be a part of something greater than themselves.

Credits

Edited and condensed for clarity. Interview conducted in April, 2021. Photography by David Evan McDowell.