Layers of Fear can’t transform the tortured artist trope

On January 2nd, George R.R. Martin came clean with his readers about his progress on the sixth book of A Song of Ice and Fire (1996-present): Winds of Winter would not be published before season 6 of Game of Thrones (2011-present) goes to air on HBO. Readers could choose not to watch the show as it is released, but as any basically sociable person with a stable Internet connection knows, dodging Game of Thrones spoilers is a hopeless occupation. Martin explained his disappointment in a long post on his blog with an apology that laid bare some of his anxieties about the creative process, namely that he has little control over the timing of his breakthroughs. Frustrated fans aren’t wrong to feel that this is a cop out, but writers of all stripes can sympathize with his predicament. As Martin puts it most succinctly in his blog, “Sometimes the writing goes well and sometimes it doesn’t.”

Thankfully, Martin has the good sense not to comport himself like God’s wide receiver when it comes to churning out his work. No real writer has time to sit around waiting for inspiration to hit them out of the clear blue sky, and all the good ones have their own processes for getting the job done. While alive, John Updike used to force himself to write 1500 words a day—no excuses. Jonathan Franzen once glued a severed Ethernet cable into his office’s telephone jack so that he wouldn’t have the Internet to distract him while working. Inspiration itself isn’t a myth, but as just about any professional artist will tell you, the surest way to come upon it is to wrestle it out through diligent work.

It’s in the throes of this creative turmoil that Layers of Fear begins with its protagonist. He is a painter (his name withheld throughout the game) who met with some acclaim earlier in life and is now killing himself to complete his masterpiece. As you might expect from a game touted as psychological horror, things are not going well so far.

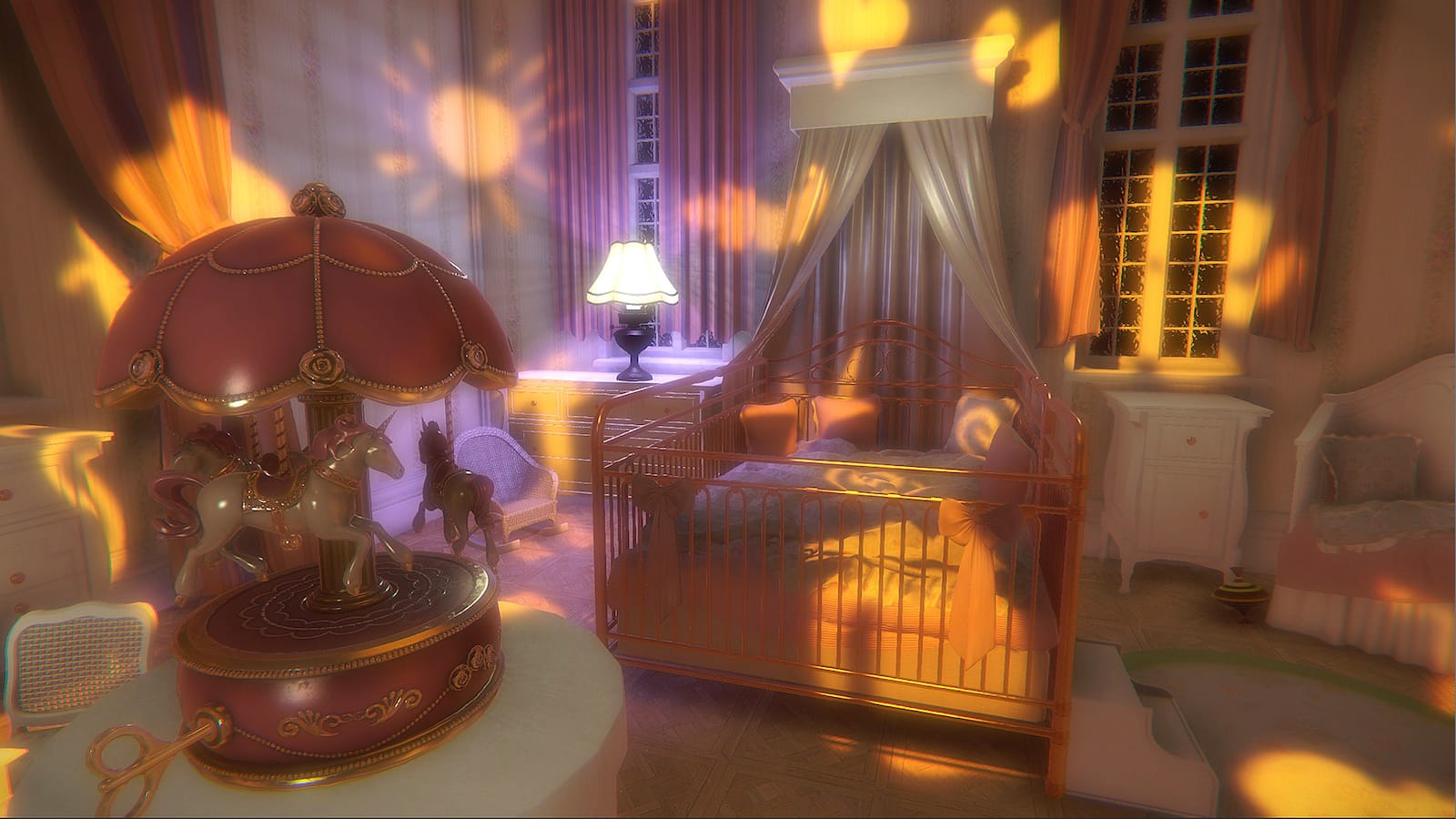

As the game begins, you stagger over the threshold of your impressive Victorian home, coming in late out of a wet, gloomy night. You’re presumably drunk—you soon discover that drinking is about the only thing the protagonist does consistently well these days—and your vision bobs and sways with your body as you look around. The house is fairly neat and furnished handsomely. It’s dimly lit, but little is amiss as you initially explore, finding notes and scraps that begin to ground your fuzzy, drunken mind back in the real world.

YOUR VISION BOBS AND SWAYS WITH YOUR BODY AS YOU LOOK AROUND

The walls of the stairway are hung with paintings almost to excess, but then, as you head up to the second floor, you realize that they comprise a kind of anthology for the painter’s morbid tastes. Most of the works have an unsettling undercurrent, if they’re not openly creepy. Francisco Goya’s Portrait of Tio Paquete (ca. 1820) peers oppressively over your shoulder as you turn the corner on the landing, and Rembrandt’s Stormy Landscape (ca. 1638) rumbles overhead. This trend continues throughout the game with each work reflecting some aspect of the protagonist’s inner life, whether it’s a fascination with violence, old world gentility, the pain of loss, or just plain moodiness.

Before you begin trying to navigate the endless labyrinth of halls and rooms that make up this haunted house, you’re given a quick glimpse of the protagonist’s own art. The studio itself is a spare room, dominated by a large easel near the center. A few trunks are stationed by the walls, some filled with the bottles of liquor that fuel the painter’s manic midnight vigils. The trail of notes you follow to his studio begin to show just how withdrawn the protagonist has become. He stays up most nights, working without eating or sleeping for days at a time, without any regard for the wellbeing of his family.

In short, this guy is a classic Tortured Artist, a caricature about as subtle as a Banksy stencil at Disneyland. He’s neurotic, self-obsessed, misogynistic, and thoroughly convinced of his own superiority. And most annoying of all, this guy is an absolute zeppelin of hot air. He has almost nothing interesting to say, and the ultimate object of his obsession (to say nothing of the grotesque way he intends to satisfy it) is painfully shallow.

However, after two playthroughs, I still wonder what exactly Bloober Team intended to say with this character. On the one hand, they could be delivering a send up of the tortured artist trope—a welcome one, because characters with this magnitude of self-seriousness desperately need to be taken down a peg. This painter seems loathsome by design, and his self-imposed isolation is almost cast as a dangerous withdrawal from family and society. On the other hand, the painter is the character with whom you are asked to identify most directly. For all his craziness, the game wants you to admire his ambition and dedication to his craft, to feel sorry for his loss, and to understand how he found himself on his path to madness. But that is a step I can’t take. In the end, he’s just a hateful, selfish jerk.

You spend the entire game stumbling in this artist’s shoes, searching through room after room for information about the house and the small cast of characters that occupies it. The trick of it is, after seeing the whole layout of the house in the prologue, you’re never comforted with that stability again. Old rooms and new ones present themselves on the other side of each successive door with no consistent logic. You’re completely at the whim of whatever forces—supernatural, psychological, or otherwise—are designing this harrowing journey through your own home.

YOU SPEND THE ENTIRE GAME STUMBLING IN THIS ARTIST’S SHOES

As an attempt at defamiliarizing this familiar domestic space, walking through the game feels like a series of exercises in recreating the chill of P.T.’s (2014) single hallway. On the whole, they’re executed with some modest success. The manipulation of environment is most effective when it is most cerebral, as when you look up to see that the walls of your office extend to dizzying heights, or when a basement room full of discarded furniture is suddenly relieved of gravity.

Moments like these make Layers of Fear worth playing. Yet as beautifully disorienting as the game can be, it ultimately has little interesting to say about artists and less to say about art. Stomaching the jump scares and heavily recycled horror imagery will earn you a handful of mesmerizing vistas, but Layers of Fear fails to challenge or transform its central trope.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.