The legacy of Metal Gear’s virtual worlds

Volume is a game that wears its influences on its sleeve, and none seem to loom as large over the project as the spectre of Metal Gear Solid. In talking about Volume, the developer, Mike Bithell, has been upfront with his admiration for the series, particularly the first two installments. Talking to Eurogamer early in his game’s development, he said that he was drawn to Metal Gear‘s “cleverness”:

“As stealth moved on it became so much more visually complex and detailed. Those games are great, but it just lost the purity for me, of knowing exactly if an AI can see me. I wanted to try and make a game that went back to those things I liked.”

It’s a bit of an ironic complaint; if any game series has lead the games industry in its charge toward complexity, it’s Hideo Kojima’s frequently byzantine adventures, with their increasing insistence on visual and environmental fidelity and their tendency toward mechanical and narrative maximalism. If Bithell’s—and Volume‘s—nostalgia gestures toward anything, it’s one of the aspects of MGS that got lost in the transition from 2 to 3: the VR missions. The fixed camera angles and the guard’s clear vision cones are canonical MGS, but the digitized environments, their mood and aesthetic and layout, is all VR.

///

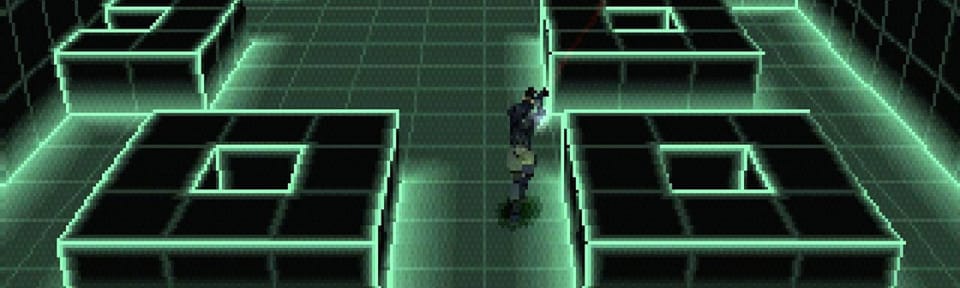

The VR missions play a liminal but important role in the first two MGS games. First introduced as part of the Metal Gear Solid: Integral special edition release in 1999, these bonus missions let the player navigate Solid Snake through an additional regimen of stealth- and combat-based challenges, ratcheting up in difficulty as they went. In these first outings, VR resembles the blocky vector graphics of the ’80s, one light cycle away from Tron. They’re all crisscrossing lines of light, sharp corners, and backgrounds in all black. VR is almost an oppressive space in this outing, somewhat eerie in its suspension from black nothingness. Imagine crawling through cyberspace in the middle of the night.

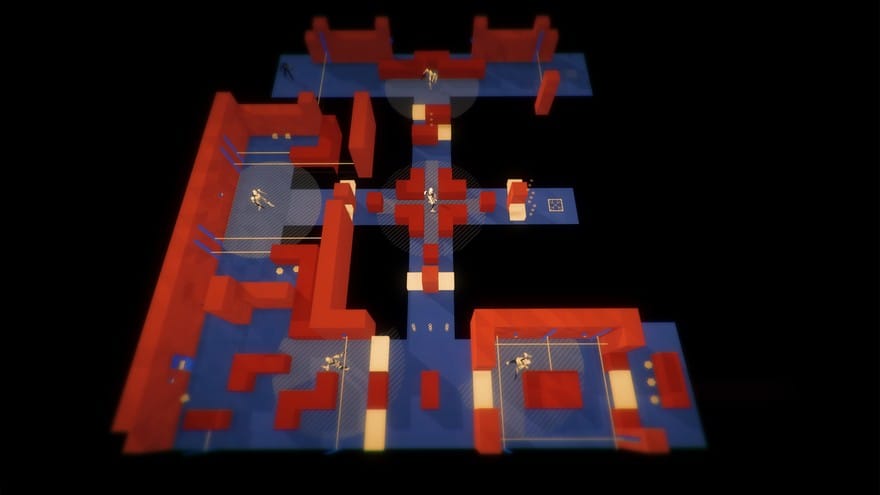

A more complete and aesthetically distinctive version of the missions returned with the Substance re-release of Metal Gear Solid 2 in 2002. These missions showcase a more distinctive VR aesthetic—the blocky vector art is replaced by almost organic curves and chemistry-inspired latticeworks, with gentle blues and oranges replacing the greens and blacks. They’re still, essentially, blocks of terrain suspended in blank space, but the space is brighter, and pockmarked with twisting packets of data, analytics and unreadable lines of code, like clouds in the morning sky.

Imagine crawling through cyberspace in the middle of the night

As the final and most complete expression of Metal Gear‘s VR aesthetics, the missions in Substance a welcome change of pace from the core narrative game. The claustrophobic corridors and slasher-film camera angles of the tanker and Big Shell are replaced by smooth lines and open spaces, mimicking the basic design of these levels without the attendant tension. And the bright colors—the enemies are rendered in a fluorescent orange, disappearing into flakes and fading away when “killed”—make everything feel a bit sillier and more playful. It’s Metal Gear‘s “Stealth Espionage Action” as an arcade game, divorced from all the intensity and stakes of the surreal military thrillers that usually contain it. VR is free of cutscenes and codec calls, stripping away everything but the stealth challenges themselves, offering a tighter, more singular experience than the main games themselves.

That paradoxical relationship—where the VR missions offer arguably a purer, more straightforward articulation of Metal Gear Solid than Metal Gear Solid—is further highlighted by the fact that the VR missions actually play a strange side role in the fiction of Kojima’s universe. VR functions as a training apparatus for Metal Gear‘s soldiers, most importantly teaching MGS2‘s protagonist, Raiden, how to fight and move like Solid Snake himself. The psychological and philosophical implications of VR are considered at length in MGS2‘s plot—Snake himself sneers at one point, almost winking at the audience as he says, “War as a videogame. What better way to train the ultimate soldier?” Later, as MGS2 famously descends into elliptical madness, it’s implied that too much time in VR might have fragmented Raiden’s perception of reality irrecoverably.

It’s funny, then, that the actual VR missions the player has access to are so deliberately and clearly marked as unreal. If anything, one could imagine these missions, with their bright-orange sentries, occasional giant soldiers, and floating lines of code, reinforcing the boundaries between the real and unreal rather than breaking them down. And for the player getting these games as they come out, VR isn’t the training crucible it is for Raiden. They’re additional challenges, dexterity tests with more mechanical meat than the game proper.

These contradictions—more “pure” but less central, reality-shaking yet decidedly unreal—mark VR as an outlier in Metal Gear‘s self-conception, an aspect the games themselves can’t quite make sense of including. And yet the names given to the editions that include them—Integral, Substance—also suggest that they’re the central part of the package. If anything, the VR missions encapsulate the early Metal Gear Solid games’ contested relationship to their own gameplay. The way gameplay can exist outside of narrative context, the possibility for carefully controlled stealth segments to explode into violent shenanigans: Metal Gear adores and abhors these things.

Metal Gear, after all, wants to go higher places

Metal Gear, after all, wants to go higher places. When asked what the first three games are about, Hideo Kojima famously doesn’t gesture toward anything mechanical. He gestures toward themes. “Gene, meme, and scene” is the motto-ized version of Kojima’s intended goals for the early series. For such a film-inspired gamemaker, then, a more abstracted presentation of gameplay, without plot, must be terrifying. This emergence is essential to the identity of the series, and represents some of its most laudable parts, but you can sense a distinct vulnerability in the way it’s presented without contextualization in the VR missions. These are what you love, it says. And we want you to enjoy them. But please don’t think that’s all we are.

///

It’s that move toward abstraction, though, that might be the real legacy of the VR missions. Metal Gear Solid‘s VR missions were made simplified not for the sake of hardware limitations, but for artistic interest, as a means of foregrounding the stealth mechanics and deliberately showcasing the artificiality of them. It prefigures the move in games toward deliberately lo-fi aesthetics and non-representational spaces, both for the aforementioned reasons and because maybe blocks and pixels have stories to tell, too.

It’s a trick Volume borrows, attempting to inject a very human Robin Hood tale into Metal Gear‘s world of floating code and vectorized henchmen. And while it’s not the legacy people typically think about when reflecting on Metal Gear, maybe not even the one Bithell is consciously pulling from, it’s an important one. After all, like Snake said—what better way?