“I never thought I’d talk to my principal about menstruation,” Sophie Houser, one of the two high schoolers who created Tampon Run at the Girls Who Code summer program, admits. “Or even my teachers. Like, all people really—I feel so comfortable now just saying, let’s talk about it.”

“Yeah,” Andy Gonzales agrees. “I told my comp-sci teacher about [Tampon Run] ’cause he had given us a talk on the gender gap in the tech industry. And the next day apparently someone left a tampon on his desk after he told people about the game. And he was like ‘Oh cool! A tampon. I get to throw this at someone.'”

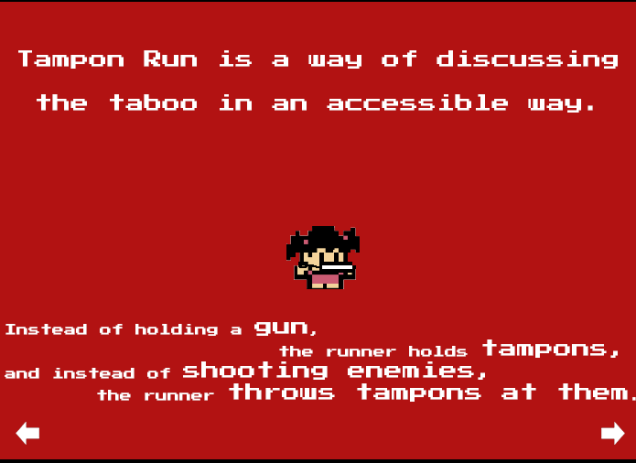

Tampon Run, if you missed its coverage on everything from Jezebel to Time, is a simple platformer with ambitious goals. Your spunky, pixelated avatar runs across the screen to the right familiarly, defeating as many enemies as possible while conserving ammo. But your weapon? A stash of absorbent, white cylinders.

And yes, Andy’s comp-sci teacher was dead-on. Throwing tampons at people feels very, very cool.

Like many good ideas, Tampon Run began as an outrageous suggestion that struck a chord. Both Andy and Sophie were adamant about using their coding skills gained from the program to promote social change. “So I jokingly said, ‘Maybe we can make a game where someone throws tampons at people’s faces,'” Sophie laughs. “And as soon as I said it we actually realized there was something there. Because Andy and I started talking and realized we’d both experienced the menstrual taboo.”

After researching online about their observations about the phenomenon, the girls realized that the menstrual taboo was “something bigger than our own experiences. It went on around the whole world.” Sophie mentions finding out about rituals still practiced today that isolate menstruating women, rendering them a total outcast of their community simply for undergoing a natural bodily function.

In their own experience, both girls (like most girls) remember slowly noticing how said natural bodily function gets regularly treated like an unmentionable horror in social situations. Sophie noticed when periods were just about the only thing she couldn’t bring up in her close group of guy friends, who otherwise delighted in talking about anything and everyhing with some kind of a gross factor (i.e. poop, peeing, general gross human things). Andy recalled a day in middle school when she walked down the hallway only to discover a huge crowd of scandalized people looking down at an unused, unwrapped tampon on the floor. “I just threw it out,” she concludes, a little indignant. “Because I was just so confused why everyone was making such a big deal about it.”

“I was just so confused why everyone was making such a big deal about it.”

That mixture of both confusion and uncertainty followed them both into the development of Tampon Run. Andy went into it as no stranger to making games with a feminist angle, since the first one she ever made was a project for English class “where all you had to do was control Odysseus as he walked through a 30 second platformer and sweet talked his way through all the ladies.” The project was meant as a critique “because all the women’s roles were to either sleep with Odysseus, or be evil, or both.”

But both she and Sophie, though certain about the importance of their idea, experienced some hesitation when confronted with the deep roots of society’s oldest taboos. The teacher supervising their brainstorming session at Girls Who Code, for example, even paused at the idea first. Because, though excited by the concept, he questioned whether the girls would be allowed to pick such a risque subject. But after receiving an enthusiastic approval from higher-ups, they went through with the idea.

The more Sophie and Andy researched and discussed about the taboo, the more they realized how ridiculous it all was. Yet, despite that, both felt an ill-defined uncertainty during its development. Andy found herself incapable of bringing up the premise of her game to her own parents. “And I couldn’t tell if that was just because I wanted to surprise them or if I was scared to tell them,” she confesses. Her parents praised the parts of the game they saw out of context, only discovering its true subject matter at the final presentation. But when they did finally see her work, “they were really supportive! Which was awesome.” Similarly, Sophie says her mom showed some initial trepidation, before feeling nothing but pride after seeing the final product and witnessing the game’s poignancy for herself.

The menstrual taboo is complex parasocial territory for young girls to navigate. Though the terrain has certainly improved in recent history, boundaries remain uncomfortably unapproachable, especially in first experiences. On one hand, Sophie remembers feeling that initial excitement, since “at the time, it feels like, wow, I’m part of this kind of girls club. And I still feel that way. Like, I have my period and that’s something women can all talk about and relate to.”

Andy also remembered it as a mostly positive experience too, where “I felt like I had gone through a rite of passage. I swaggered into school, like ‘I’m on my period—that’s awesome.’ But I didn’t tell people because I just didn’t feel comfortable. But it kind of felt like now you’re really a woman, or really part of this community in body, mind, and soul.”

Most girls can remember this rush of mixed emotions: I’m a woman, I’m healthy—and I should probably keep quiet about it. I for one couldn’t figure out whether to be more horrified by my mom’s exuberant celebration, or my own sense of pride for having gotten it before my best friend did. The pride, I think, came from believing myself more grown up. The horror, I know, came from an implicit understanding that this rite of passage was one that should remain a silent victory. (A silent victory I liked to remind my best friend about in private.)

Improving the menstrual taboo is not about girls loving or exhibiting their periods for all the world to luxuriate in. It’s about not having to shove tampons up your sleeve, Assassins Creed-style, before excusing yourself for the bathroom. It’s about being able to tell your boss you have cramps, not the flu, and that’s why you can’t come into goddamn work today. It’s about having a conversation about menstrual blood that doesn’t treat it like some unholy combination of feces, urine, and semen.

Sophie and Andy seem most proud of the subtle effects their game is having on the way people around them talk about periods. One of Sophie’s aforementioned guy friends approached her after playing the game, only to agree that he’d been incapable of talking about it before and “I don’t know why, that’s so weird.” While recently working on homework for her comp-sci class, Andy heard some peers cracking good-natured tampon jokes in a way she’d never heard before. “Even if you compare the way we talked about menstruation back then to the way we talk about it now,” Andy says, referring to her and Sophie’s journey with Tampon Run, “it is so much more comfortable. There’s been a huge difference in my personal ability to discuss menstruation.”

Part of what attracted them to coding and videogames as a medium in the first place was just how far they imagined their conversation starter could reach. “Videogames are just so accessible. Anyone can play a game and it’s a fun way of interacting with a serious issue,” Sophie says. Because while some might be unwilling to discuss an uncomfortable topic head on, a great way to get past that is to “blend it with satire, until people are willing to take the serious issue in much more.”

It’s about not having to shove tampons up your sleeve, Assassins Creed style, before excusing yourself for the bathroom.

The power of coding, whether in gaming or otherwise, has stuck with both of them throughout the experience. “I loved feeling like I made a change in the world through coding,” Sophie says. As her first serious dip into programming, she discovered how empowering it felt to “start out with nothing, and then after so many frustrations, your thing works and it’s on the screen and you know that was all you behind it. It was all your code that made that happen.” Andy emphasizes just how much those frustrations were part of it for her too, though “I know the more frustrated I feel, it’ll only be that much more rewarding when I finally get it to work—if I get it to work.”

Though their efforts to make social impact through tech may not strictly continue into gaming, both Sophie and Andy are examples of just how far an industry-wide discussion on gender issues can go. Andy specifically referenced Anita Sarkisian’s tropes vs. women videos as an inspiration. And my conversation with these two teenage spitfires echoed a hypothesis I put forward at the end of my article exploring the menstrual taboo in games. Slowly but surely, things seem to be changing. And they’ll keep changing, as long as people keep talking about them. The new generation has all kinds of tools at their disposal to help facilitate all kinds conversations that society has been long overdo.

Perhaps the most convincing evidence of change in this particular battle is the fact that the only hatemail Tampon Run has received (as of yet) was an email that labeled its creators misogynist. The complaint was sent by a group called All Men for Feminism. But predominantly, the emails flooding Tampon Run‘s inbox from people all over the world express nothing but gratitude for the game—a thanks to Sophie and Andy for one hell of an adorably-packaged and impactful conversation starter.

I think the subject line of the girls’ absolute favorite piece of feedback summarizes it best: “‘I’m a big old hairy dude and I loved the heck out of your game.'”