Literature games and the future of book publishing

It was called “the end of days” for literature. Bold doomsaying letters across headlines predicted that with the financial crisis of 2007-2008, the era of books would meet its untimely end, and the larger publishing world would be rendered obsolete. But traditional books didn’t die—they simply fled into the digital world and returned with new forms, the technologically-savvy ebook and digital story app. The need to diversify the medium that arose during this era is, in part, what may have kept sales of books rising through the apocalyptic flames. It pushed against any stubbornness in the publishing world and proved that both page and screen could work in tandem to tell, and sell, stories. There is a similar effort coming from the other side of this dichotomy, in the form of videogames that are experimenting with becoming more literary in nature. The parallels here prompt the question of whether it is imminent that the two increasingly amorphous mediums—books and videogames—may intersect to present a whole new manner of storytelling.

There are those who believe that intersection is already happening. Publishing company Madefire hypothesizes that the innovation of non-visual storytelling that we are most familiar with, such as books, is inevitable—visual, digital stories present a new way to further explore how we can most effectively or most interestingly tell a story. I was curious to test Madefire’s claim. Through the Madefire app, I bought a comic book version of a Japanese retelling of The Brothers Grimm’s Snow White, and sincerely enjoyed the interactivity of the comic. The app panned across and zoomed in on dialogue, like a moving camera that ensured that I focused on the narrative without moving a panel ahead. It felt almost cinematic, or as if it were a magical comic book straight out of Hogwarts. With a tap of my finger, another panel emerged; Snow White is shown walking across my phone screen through falling snow as more text is revealed. The unfolding panels and moving characters are reminiscent of the Emote Lite 2D animation technology boasted by D3 Publisher’s otome games (narrative-based visual novels specifically targeted towards women), where characters are seen on the screen similarly moving their mouths and making subtle gestures. Throw a few dialogue choices and branching story lines into the Madefire digital books, and yeah, you’d have a range of decent otome games.

a reading experience that felt akin to watching a cutscene in a video game

Sure, the Madefire app is meant to tell stories, to bring books to life, but if you were to ask me whether it felt more like an digital book app or more like a visual novel (considered a videogame despite the misleading name) I’m not sure I could decide. The digital comic book version of Snow White, like any traditional book, gave me no dialogue choices and hardly any autonomy—I couldn’t even speed up the pace at which the text and panels moved like you can in most otome games and visual novels. But there were aspects of this digital book medium presented by Madefire that felt very visual novel-esque, in ways no book or ebook I’ve known could be, resulting in a reading experience that felt akin to watching a cutscene in a videogame.

Tapas Media is another company seeking to blur the line between books and games as storytelling mediums through a free mobile app system. Tapas is unique because it uses the concept of “free-to-play” games but applies it to mobile reading. For example, for every chapter (which Tapas calls “episodes”) of a book you read, you can obtain and use in-app gift boxes, or peer-to-peer rewarded sharing. In other words, you can read a free book, and in doing so, unlock episodes of other books—you can also purchase virtual “keys” to unlock certain books. As their website touts, the Tapas app is “Candy Crush Saga meets mobile content”—insofar as Candy Crush was aimed at “casual gamers,” Tapas’s books are aimed at “casual readers.” There are little to no illustrations or moving images in a Tapas story, unless you choose to read a comic, but the mechanics of obtaining more stories are certainly game-like, and purposefully so.

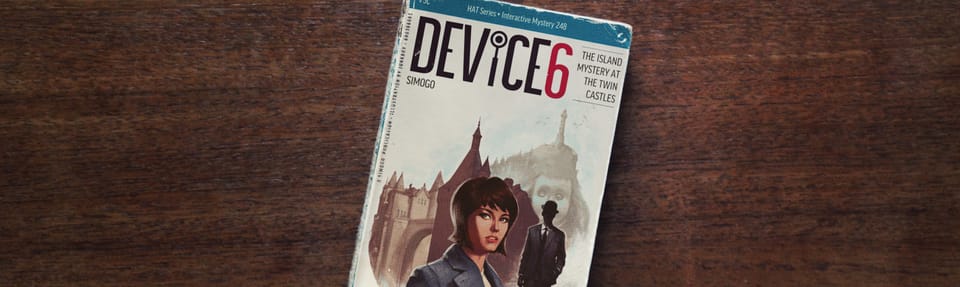

Madefire and Tapas both present examples of publishers breaking into the digital realm. But unlike Madefire and Tapas, newly emerged company Simogo isn’t a book publisher; it’s a Swedish game studio that makes games that read a lot like literature. Sort of. Simogo specializes in games without a genre—as Simogo states on its website, “we’re not overly concerned about whether or not [our products] are even games.” As such, Simogo has created apps like Device 6 (2013), described as “a surreal thriller in which the written word is your map, as well as your narrator.” At its core, Device 6 is an app that seeks to tell a story, but also allow the reader to interact with aspects of the story.

{"@context":"http:\/\/schema.org\/","@id":"https:\/\/killscreen.com\/previously\/articles\/literature-games-future-book-publishing\/#arve-youtube-hdnjxql6muk","type":"VideoObject","embedURL":"https:\/\/www.youtube-nocookie.com\/embed\/hdnjXQL6Muk?feature=oembed&iv_load_policy=3&modestbranding=1&rel=0&autohide=1&playsinline=0&autoplay=0"}

For example, as the main character Anna finds a “curious lock-like device,” the reader scrolls through the text to find a moving picture of said device and can click it, even play with it. When Anna is walking down a hall, the very sentence describing her movement shifts across the screen in the direction she is walking. It’s the text of the story itself that draws the reader forward, literally: the app takes advantage of your phone’s accelerometer and follows the text no matter what angle the phone is held at. And instead of branching decision trees like in a game, the text itself divides into branches, leading to different outcomes of the story. I could choose, for instance, for Anna to stay walking on the ground floor by merely reading forward, or I could begin reading a path that forces Anna to walk downstairs, where the sentence splits off and meanders literally downward. The text is the story, and also the space, the setting, and the geography.

As Madefire and these other companies are surely aware, some videogames present an excellent medium for not only storytelling, but also for the retelling of books. In particular, narratological games present a scenario where a story reader can balance the line between complicit observer and active participant of the narrative. Unlike books, such games provide player autonomy within the scope of a broader story, allowing interactivity with a set environment and its characters. The player, like the protagonist, becomes involved in the storytelling process and perhaps even the storymaking process, too. Such games like Device 6 are becoming a new kind of literature, a synthesis of the narratological and even the mechanics-based ludological parts of games, which together create a system of outcomes in a story, thus making a story more dynamic.

a reader can balance the line between complicit observer and active participant of the narrative

Scholar Jonathan Ostenson posits of the evolution of games: “There’s a place for a purposeful study of videogames… because they represent some of the most important storytelling in the 21st century. This new medium… represents our society’s efforts to push the boundaries of storytelling in meaningful ways,” which shows that at least some videogames can share the literary quality of a book. In his view, the intersection of videogames and books, as the two mediums further evolve, is almost a natural one—the seeds of which have been sowed—resulting in the digitalization and increased interactivity of books, as well as games with lush worlds and characters robust as any other literature. And maybe he’s onto something: The Witcher videogame series is one popular example of a game studio taking a story originally told through the medium of books and relaying it through the lens of a videogame. The games are based on a series of Polish novels written by Andrzej Sapkowski, and allow fans an unprecedented level of interactivity, moving the fantasy from paper to screen. Another example can be found in the game 80 Days (2015) by inkle Ltd., which is based on the classic 1873 Jules Verne novel, Around the World in 80 Days. And conversely, Dungeons & Dragons, the role-playing tabletop game, began as a kind of analog story, albeit with some game mechanics, but later became the foundation for several videogames, such as the Baldur’s Gate and Neverwinter Nights series. Book authors themselves have made the switch between mediums, such as Sam Maggs of The Fangirl’s Guide to the Galaxy: A Handbook for Girl Geeks (2015) fame, who is now one of BioWare’s newest game writers.

That some videogames are now giving the option of two separate play styles—story-driven or tactics-focused—could perhaps be further indicative of the potential meeting of mediums. This is the case for the latest installment in the Fire Emblem series, released earlier this year. Nintendo offered two versions of the same game, each presenting a different side of the same story: Birthright, which is story-focused, and Conquest, which is tactics-driven and is generally more difficult. Giving players the choice to play games that allow a focus on storyline is significant because it acknowledges that maybe some games or modes can, for all intents and purposes, be read rather than played. Indeed, it appears the only significant difference between a book and a videogame is their level of interactivity. It’s this difference that divides the digital novel from the otome game, for example, despite both often involving heavy amounts of text. Digital novels are comprised of primarily text, but require no interaction with the story, whereas otome games are also comprised of significant amounts of text, but require interactivity to change the outcome of the story.

Writer Maxwell Neely-Cohen suggests that the “literary world and the videogame world could greatly benefit each other,” and further that “even a conversation, let alone the beginning of real collaborations and dialogues, would help each contend with their respective shortcomings,” such as the lack of diverse representation across both mediums. To this point, Neely-Cohen further writes that “publishers [c]ould collaborate with indie game developers,” much like a comic book writer collaborates with an artist, and that “literary magazines and libraries [c]ould sponsor gamejams,” increasing accessibility and inclusivity by providing their unique writing resources and beta readers to game writers. Some book publishers are already dipping their toes into the depths of the music industry, creating soundtracks for books. A logical next step could be that videogames become a medium for book publishing, as publishing companies like Madefire appear to be doing already. Either way, the rise of ebook sales in both unit and dollar terms means the digitalization of stories is, at least for now, inevitable, and how that will affect videogames is something to watch out for.

Header via simogo.com