Long Live Grim Fandango

This article was funded with support from Longreads members.

In 1987, Tim Schafer sat in a lecture hall at University of California, Berkeley. Professor and anthropologist Alan Dundes spoke about a ritual found in Mexican culture, where family members welcome the dead back into their homes. Stories of The Day of the Dead, or El Dia de los Muertos, fascinated Schafer, then a budding writer and computer programmer. A decade later, he wrote a videogame—ambitious, over-budget, late—inspired by these tales. Grim Fandango was the last of a dying breed, a PC adventure game beset by constantly advancing hardware and an audience raised on faster, louder, flashier alternatives. You have likely never played the completed work.

Because, like so many of its characters, Grim Fandango died. It succumbed as any late-’90s computer game on CD-ROM would, its jewel case an inevitable coffin. The game was built for Intel’s 386 processor; one year later, the 486 arrived. Computer games rely on a web of interlocking code that resembles more a cityscape of cards as opposed to a single, measly house. Every passing year, as chips got faster, the game’s architecture eroded and aged until finally this towering game tumbled down. In 2015, the only way to play the original Grim on a modern computer is to download special files modified by a fanbase that put years of effort into keeping the game alive, the work of a patient and overzealous mortician.

There is no wrong way to mourn those lost to us. Some remember. Some let go and wait for their return. But no matter the macquillage, an ugly dead thing remains ugly. Grim Fandango— the long-deceased original—is beautiful and strange and smart, an improbable marriage of disparate cultures and time periods, of plots and puzzles and balloon animals the shape of Robert Frost’s head.

There is an old interview with Schafer from 1997, the year before Grim came out. A reporter is asking him about LucasArt’s next big game, wondering what the next “holy grail for gamers” is. The interviewer surmises a few: “Better graphics, better sound, better interface?” Schafer answers. “We try to do a real story, a complicated story, with real human involvement.”

Today Mr. Schafer describes Grim differently. He’s 47, divorced from the now-defunct LucasArts and a decade into his own studio Double Fine Productions, who, along with Sony, is bringing Grim back to life for modern systems. Grim Fandango Remastered is a celebration of a game gone too soon, a belated wake seventeen years later. For a small contingent, this act of faith is a validation of their love—for the rest of us, it’s a chance to experience a lost masterpiece. “It’s kinda nuts, this game,” he says. “You’re playing it and all of a sudden you’re standing in a sewer with a giant white alligator and you’re wearing an aztec mask.”

Into the sewer, then. It is time to welcome Grim Fandango back into our homes.

***

At the time of its release in 1998, Grim was celebrated for its droll fusion of ‘80s-era capitalism and ‘60s-era beat poetry and ‘30s-era gangster noir, all wrapped in Mexican folklore and dipped in custom hot rod chrome. To a small circle of passionate fans, the game remains the best they’ve ever played; the enthusiast site AdventureGamers.com voted Grim the #1 Adventure Game of all time. Metacritic, the aggregating media review site, scores the game an almost unheard-of 94 out of 100. The early videogame website GameSpot.com awarded the title its coveted “Game of the Year” award in a year stuffed with classics you’ve actually played: The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time; Metal Gear Solid; Pokemon Red & Blue.

Grim is a point-and-click adventure game without the pointing and clicking.

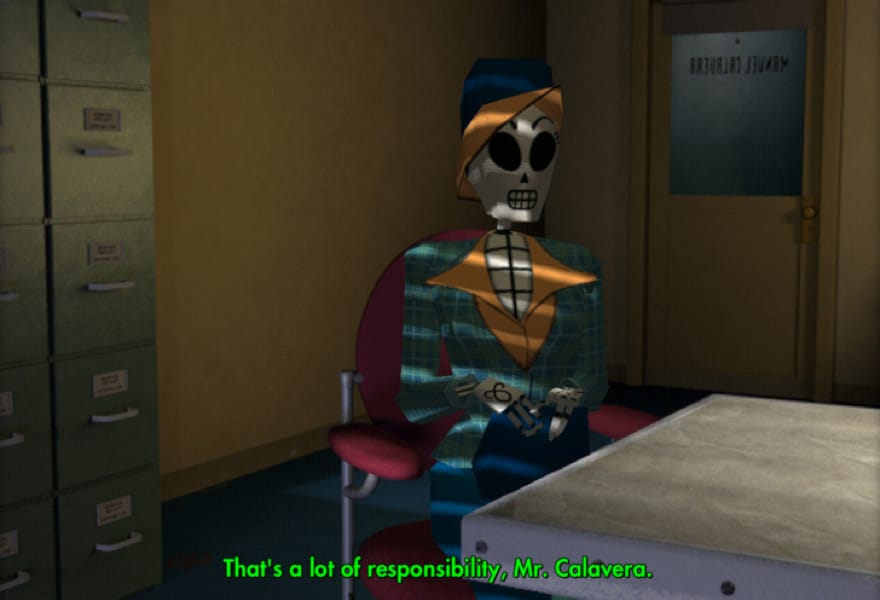

Grim is a point-and-click adventure game without the pointing and clicking. You play as Manny Calavera. He is dead but so are his clients. His job is two-fold: Gather the recently deceased from the Land of the Living and transport them to the Land of the Dead; Try and up-sell them plush travel arrangements they’ve earned through living productive, generous lives. Manny is reaper and travel agent, both. Jerks and hooligans suffer the cramped confines of a stuffy coffin; only the pious get to ride the Number 9 Train.

This is no traditional hellscape. The dead (including Manny himself) are represented as walking calaca or calavera, those Day of the Dead skeleton dolls. You’re chauffeured by a demon auto mechanic styled after Ed “Big Daddy” Roth’s hot rod monsters, the creature’s eyes bugging out and tongue flapping in the wind. Later on, you walk for miles on the netherworld’s ocean floor and fight a submarine-dwelling octopus. And yet within the fantastical malarky there is a heart.

Early in the game you uncover a covert operation to steal tickets from the righteous and sell them to the rich, damning an innocent client to an afterlife she never deserved. Now you’re a target and a schmuck. Time to make amends.

***

Schafer says that for many of his games, the world came first. The motley cruisers of Full Throttle, a 1995 adventure game about bikers (and his directorial debut), stemmed from a friend’s anecdotes from Alaska, where she’d frequented a biker bar; hearing stories of this sub-culture too frequently boiled down into Angels from Hell lead Schafer to believe this was material worth plumbing. Psychonauts, a surreal platforming game for the Xbox and Playstation 2, slid out of a long-percolating idea that began in a “Psychology of Dreams” course Schafer had taken in college. What would happen if we could travel through someone else’s subconscious? (Instead of Mario’s Ice and Fire worlds, the main character Razputin Aquato visits different characters’ brains, their neuroses constructing inhabitable levels such as The Milkman Conspiracy or Milla’s Dance Party.)

The Day of the Dead intrigued Schafer as a spiritual ceremony that, through the influence of Mexico’s Bureau of Tourism, became an image to stamp on calendars and travel brochures. The DayGlo sugar skulls and rampant commercialization of what was once a quiet, family-led time of remembrance did not sour his regard for the event. “[When Day of the Dead] became more of an industry, that made it more appealing to me,” he said, adding that the festival became “more based on the immediate needs of people who are alive.” This, plus the implications of a corrupt underworld, sowed the seeds for what would become Grim Fandango.

When Schafer and his team pitched their new game to LucasArts in the summer of 1996, most everyone at the table loved the idea. Then a lone detractor raised his concern. “One person was like, ‘Um… isn’t it a bummer that everyone’s dead?’” Schafer remembers. The Grim team countered that, no, that wouldn’t be a problem at all. In truth they had no idea.

Today, Schafer understands the squeamishness. “Some people are put off by death and don’t want to think about it or talk about it,” he says. Death is depressing to many, or it scares them; a game with a dead guy on its cover was a risk. I suggest it was smart to tell the story using animated calaca dolls instead of, you know, rotting corpses.

“But look what’s popular now?” Schafer says. “Rotting corpses. All the biggest games and TV shows are rotting corpses. I underestimated the public’s demand for rotting flesh.”

“All the biggest games and TV shows are rotting corpses.”

Later, Schafer tells me via email: “I had one worry about making a game about death: What would we do if someone close to the project died? For some reason, I knew it would happen.”

So he devised a plan. He describes a scene showing spectral lights dancing in a forest; these were pure souls allowed easy passage to the Land of Eternal Rest. The end sequence would include these lights racing off to their reward with text on-screen naming the dearly departed. The idea was scrapped during production and never made it into the final product.

During Grim’s first act, Manny visits the Land of the Living to gather a client’s soul. Those still alive appear as cardboard cut-outs, their faces a fractured collage of eyes and nose and mouth glued together like ransom notes. Move Manny close to one of them and he utters an aside to the player. It is voiced by actor Tony Plana but written by Schafer: “It is the fear of death that makes monsters of us all.”

***

Grim Fandango is not your typical undead-fest filled with violence and guns. Most of your time playing will be spent in conversation with the game’s wry inhabitants. Grim leans hard on the tough charm found in Raymond Chandler but with an acerbic, absurdist intelligence, as if penned by David Mamet. The plot revolves around a spirit of one-upmanship the same way Mamet’s Glengarry Glen Ross (an influence, Schafer says) conjures tension and cruelty out of contemporary business mores: Someone always wants what someone else has.

Though its characters are dead, the music that scores their actions is lively and swinging, full of walking bass lines and soaring brass with the occasional strum of a charanga. Peter McConnell composed Grim’s score and has worked with Schafer for nearly two decades, composing dozens of videogames since the late ‘80s. For Remastered, he re-recorded parts of the score with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra. I asked him about working on such a complicated project, but before we discuss sound and ambiance, he refers to the spiritual.

“It’s kind of a miracle, alright.” I assume he’s describing the original being made in the first place. But he is actually referring to the new remastered version, its existence held up by numerous obstacles. Disney, who owns LucasArts, had to sign the same dotted line as Sony and Double Fine. Then there was the sheer Hidden Object Game of finding the original game.

A modern remaster requires more than the CD-ROM from 1998; any game comprises thousands of art assets, hours of recorded sound, a spaghetti tangle of programming code, and to touch up Grim Fandango meant to have access to the marrow of its boney construction, locked away in places given purposefully vague names such as “the vault.” Getting this puzzle game back in players’ hands was to be a puzzle in itself.

According to McConnell, Jory Prum, sound mixer for the newly orchestral score, cobbled together some Rube Goldbergian machine of wire and hard drives to enable access to the old material. Rob Cowles, former LucasArts marketer, rescued much of the archival data Double Fine is now using to remake the game. That’s McConnell’s term—”rescued”—not mine; even to its creators, Grim feels like something alive and worth saving.

We don’t hear what Manny hears; we, as Manny, hear.

McConnell’s composition imbued the game with this contradictory feeling: a game about the dead that pulses with life. A soundtrack doesn’t always slickly play over the action; instead a warbling jazz horn pumps in from a scratchy radio on someone’s desk. That hoppin’ band playing downstairs is first heard thumping through the floor below, then over an intercom. In a film, such diegetic (or main source) sound creates the impression of being witness to a character’s day; we’re hearing what they’re hearing, too. In a game, this immersion is amplified; we control this character directly. We don’t hear what Manny hears; we, as Manny, hear.

Though we view Manny from a third-person perspective, we have direct agency over his decisions. Press the arrow keys and he walks. Speak with someone and four lines of dialogue show on screen; the player chooses Manny’s very words for him. How you choose to interact with the world determines what happens next. Grim Fandango belies a lot of conventions—from folklore and film noir especially—but stripped down, Schafer and his team built the same machine that’s run smoothly since 1975, when Will Crowther and Don Woods made a computer game called Adventure.

***

If Grim Fandango started in Alan Dunde’s UC Berkeley lecture hall, it continued in a cluttered room inside LucasArts’ Santa Monica offices, where Schafer, lead artist Peter Tsacle, lead animator Eric Ingerson, and lead programmer Bret Mogilefsky would talk about puzzles. “We’d meet every day until we had two puzzles,” Schafer says.

An adventure game, then, is something of a misnomer. Because more than swashbuckling derring-do or dangerous questing through uncertain lands, an adventure game is defined by a specific kind of puzzle. Crowther’s and Woods’ Adventure, along with early computer games like Zork, solidified the template, consisting of rooms to enter, objects to find and use, and obstacles to overcome. These worlds were rendered through nothing but text. The only way a player can move forward is to solve a problem devised by the game’s creators. A simple puzzle: There is a locked door. Somewhere, a key is hidden. Find the key, unlock the door, and forge verily ahead.

Through the years, both the environment and your interactions therein grew in complexity. Roberta Williams’s King’s Quest series for Sierra brought rich visuals (for the time) to the genre’s until-then imagined landscapes. Maniac Mansion, designed by Ron Gilbert and Gary Winnick, added a thick skein of humor and the absurd. Half of the dialogue for that game’s sequel, Day of the Tentacle, was written by a young Schafer.

Playing Grim Fandango is as much about laughing along with its creators as it is finding solutions. This is not a “funny” game; there are no rim-shots or obvious parodies for comedic effect, as in Grand Theft Auto’s self-aware pastiche. The humor comes from an honest assessment of its world.

“Humor was always important,” Schafer tells me. “We had a big family, five kids. So the dinner table was the place to try out jokes.”

Schafer’s game writing is a continuation of that mealtime standup. Grim’s first act continues with you walking around your workplace, The Department of Death, and talking to co-workers. Upon entering the office of Domino, a fellow salesman who seems to land all the best clients and is blowing off steam by hitting a speed bag, Manny gets in a jab of his own: “Is it hard to kiss up to the boss so much when you got no lips?” While talking to your boss’s secretary, she refers to her time as a living person as “my fat days.”

These aren’t punchlines so much as observations on a world filled with skeletons. Though the plot hews closely to and is inspired by both classic and modern noir—The Big Sleep, Gilda, Chinatown—the intersection with Dia de Los Muertos makes certain the standard genre fare doesn’t stay standard.

“There’s this really rote formula for when people think about [film noir,]” Schafer says. “I loved Double Indemnity, which is a movie about an insurance salesman. Your hero doesn’t have to be a private dick. He can be just some guy who gets caught up in a shadowy underworld.”

And when the lingering stories from Mexican folklore mashed into all those Bogart films Schafer had been watching—the criminal underworld would be a literal underworld!—Grim started coming together.

One such puzzle exemplifies the moebius-strip development ethos of Schafer and his team. There’s still a lock, and a door, and a room beyond. But the world and its characters inform the riddles. Midway through the game, you’re captured by a group of underground freedom fighters. They’ll only let you go if you give them access to your building, but office security works through teeth-scans—a sly nod toward grisly deaths requiring dental work to identify the body. What to do?

The world and its characters inform the riddles.

The key equals a mouthguard (you recall Domino hitting the speed bag in his office) filled with packing foam (the dead are fragile and require travel accoutrements similar to Amazon shipments). Find one, fill it with the other, and hand over the pearly substitute; you are now free to go. The interim between problem and solution is where the player’s adventure lies: between the ears. This, incidentally, is one of the more straightforward puzzles in the game.

The genre can have a reputation for leaning too much on obtuse, arbitrary combinations. (Read a walkthrough for how to obtain the Babel Fish in 1984’s videogame adaptation of “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy” for one example of designed cruelty.) But such solutions stem not only from the desire to test the player’s aptitude. We often make up rules to govern our own IRL existence that, on their face, make little sense.

“When I was young,” Schafer tells me, “I remember checking this closet to see if there were monsters in it when I was a kid. I had to bang it three times before going to bed. For like a year, I would bang that doorknob three times before going to bed.” Schafer, like most of us, was a born puzzle-maker. He just didn’t grow out of the habit.

***

Like Schafer, concept artist Peter Chan began work on Grim Fandango long before the game existed. In 1977 he received a Star Wars magazine that sparked an interest in art; twenty years later, his illustrations gave rise to LucasArts’ most visionary creation. Last year, when Sony announced Grim Fandango Remastered at their Electronic Entertainment Expo press conference, they decorated their stage presentation not with high-res art but Chan’s original pencil drawings.

McConnell, the game’s composer, also looks at Grim as a reflection of his life’s work. In 1996, when not in the composition studio, McConnell played in rock bands and went to clubs in San Francisco’s Mission District: “On a given Friday or Saturday night you could walk around and hear the Red Hot Skillet Lickers playing at Bruno’s. When you got hungry you’d go around the corner to the cantini and there’d be a mariachi band playing.” Such nights were more than inspiration. “The Grim Fandango score was the Mission District,” McConnell tells me. “That was my life.”

A few years before the new millennium seems like high time to consider the afterlife.

Schafer grew up wanting to be a writer in the mode of Kurt Vonnegut. But as typewriters turned to microprocessors, Schafer turned his attentions elsewhere. He snuck into RadioShack to mess around with their TRS-80, an early home computer. His parents finally got him an Atari 400 and later an Atari 800; he and friends dabbled in programming, making animated title screens for made-up games but rarely pushed beyond the instruction to “Press Start.” Games were never a possible vocation in his mind, just a fun thing to do while making other plans. Then he saw a job posting on campus while attending University of California, Berkeley. The ad was for a programmer who could also write. He applied and got the job at Lucasfilm Games, which would become LucasArts. His first work there was helping to port Maniac Mansion to the NES. He then helped program and write dialogue for The Secret of Monkey Island and its sequel, and Day of the Tentacle.

Cue screen-wipe to eight years later: Schafer writes and directs his first game, using Chan’s concept art and McConnell’s score, based on biker gangs called Full Throttle. It’s a risk that pays off; the game’s a huge success. Schafer and his team are feeling confident. They’ve been kicking around an idea for awhile, melding Mexican folklore with film noir. A few years before the new millennium seems like high time to consider the afterlife. Board members want a sure thing, a sequel to what just worked. Schafer writes another thing entirely.

***

Grim Fandango takes place amongst the dead, those who have left the living behind. But in the game, the living are not an ideal the dead aspire towards, but caricatures, those frozen, ransom note horrors. When Manny returns to his world, a festival is bustling downtown. Phones ring. Cars careen down the road. This is the real, living place. What if the dead haven’t left us behind, but gone on without us? What if we are the ones rotting in place?

Grim Fandango is smart enough to not ask that question directly. But there is a sense that Schafer’s games are a response to the world proper sometimes not being enough. If his time on earth lacks a certain panache of prior eras, his games would not. Clues abound: the blatant use of a voice actor who sounds an awful lot like Casablanca’s Peter Lorre; a disparate blend of Art Deco architecture with ancient Aztec temples; cars hopped up on jet-fuel with drivers straight out of “Big Daddy” Roth’s famed pencil illustrations from the 1960s.

Schafer was introduced to Roth by his older brother, Danny. His brother loved the slick chrome and gnarly creatures, and so Schafer, in classic younger brother mode, loved them too. His brother didn’t love videogames, though, teasing little Tim for spending time chasing made-up scores or solving imaginary riddles. I asked Schafer how his brother felt about his influence immortalized in Grim. “He never got to see this one,” he says. On January 27, 1997, midway through Grim’s production, Schafer’s older brother died in a motorcycle accident.

His plan for how to work on a game about death in the midst of tragedy did not hold. The souls-of-light sequence and text dedication was never made. “What I had thought was a great tribute in the abstract just seemed like a weak trivialization compared to the actual loss,” he writes. “The only way to keep working on the project was to compartmentalize.”

Adventure games had always leaned on visual metaphors: an object glows if it can be picked up, or a verb floats on-screen, identifying what action you can perform. Schafer wanted Grim’s User Interface, the means of interaction between player and game, to be as literal and grounded as possible; everything the player saw was in the world. For example: There is no “inventory menu.” Instead, Manny takes each item out of his robe and speaks its name, as if remembering.

“He’s in the game, and almost every game I’ve made.”

Grim’s surprising elegance stems from noir’s tight economy of language, but also its creators’ desire for clarity. Death is a murky venture. The Grim player’s experience is clean, unbesmirched with the typical on-screen icons, or floating hands, or other explanatory graphics of Adventure games then and now. This is a game designed for the immediate needs of people who are alive.

If the player succeeds in solving every puzzle and progressing through the story, Manny’s earthly life isn’t restored and given back; the optimal result is a trip on the Number 9 train, a faster transport to the afterlife. You can’t go back. But you can attain a kind of peace.

Schafer’s older brother never got to see the finished product, nor would he have played it. “[My brother] always made fun of videogames and stuff like that,” Schafer tells me. “But I did find, after going through his stuff, all my games in his closet on a little bookshelf. He’d been going out and buying them.

“Danny was the one who taught me to love hot rods [and] heavy metal,” Schafer writes later in an email. “So he’s in the game, and almost every game I’ve made.”

***

On October 28, 2013, at 2 a.m., Manny Calavera spoke his first words in over fifteen years. “Good evening,” he said. “I would like to read a poem.” Across the world, sixty-four hep cats snapped in RT form.

The above quoted line is from @MannyPoetry, a Twitter Bot programmed by an anonymous fan. During the game Manny frequents a club called “The Blue Casket,” which hosts a poetry open mic. Step up to the microphone and you get to decide your poem, one line at a time, culling from such fresh jives as “I curl into a fist” and “Lugubrious” and “Don’t pet the cat that way.” The bot tweeted out a single line from Manny’s repertoire every day for an entire year.

A communal adoration forms among those who have danced the grim fandango. Fans have Manny tattooed on their skin. Web sites which sprouted at the game’s release remained active far longer than seems reasonable; Grim Fandango Network operated for over a decade, and The Department of Death played host to Grim fans for over seven years. In 2013, a troupe out of New York called D20 Burlesque organized a burlesque show devoted to Schafer’s work, Grim included. The troupe’s emcee, Anya Keister, performed as Tim himself.

The real Tim and I are talking over Skype, watching little video feeds of each other’s heads. It feels like a moment out of some movie prognosticating the future. Or a Schafer game. He’s telling me about that burlesque show, and I ask him about the game’s community of fans and why, in his opinion, the game is embraced so fervently. Our connection falters; his face freezes in place but the audio remains. Schafer’s become a character from Grim’s Land of the Living, just a caricature in stasis.

“No two people play the same game,” says Schafer’s face, stuck in digital rigor mortis. “You’ll think you’re just making a game that’s entertaining, then you’ll get this letter from someone and it feels like they’re crying, because it helped them deal with the death of their father.”

Weeks after we talk, a thing he and others created from nothing will rise again after having once been buried and gone. His mad scientist creation will not be forgotten. His masterpiece will once again exist in the present. On Skype, Schafer is still frozen and still talking, lips ever-pursed. His eyes have not blinked in minutes. He speaks as if beyond time, a living memory of the past. What future generations will think of this game is not for him to decide. “No one knows what the meaning of their work is,” he tells me. “They just know what they put into it.”