Make or Break

Getting half-lost in the streets of Porto is worth it just to be able to see the tangle of streets from Filipe Pina’s fourth-floor office. Watch the way the slope of the city bottoms out at the river, then rises on the other side in layers of bright orange terracotta roof tiles. Seed Studios is located in a historical district of Porto, one that has been around longer than most American cities. It’s a pleasure to get lost in the winding streets.

Filipe Pina keeps throwing quick glances at his screen when he’s not addressing me directly. He doesn’t look out the window onto the winding cobblestone streets and aging tile buildings. To say he’s uninterested in the past is unfair: he’s part of the Portuguese Society for the Science of Videogames, a group of people trying to find every game made in Portugal. There aren’t many, but they aren’t easy to find. Pina and his team are all young, though, and to them the past isn’t nearly as interesting as what they’re working on at the moment: Seed Studios is ready to release its 2012 Independent Games Festival contender Under Siege to PlayStation Network.

But how they got here is interesting. Pina met Bruno Ribeiro and Jeffrey Ferreira over the internet in 2000 and spent years failing at making games. Wait, that’s not entirely true: They are excellent at making games; but distributing them, getting them out into the world, that was the problem. Studio mismanagement, disappearing distributors, cowardly publishers, no contacts. (“They said to us, ‘You can only produce a game for us—at the time, for the Nintendo DS—if you have published other console games.’ We said, ‘Look, in Portugal there is nobody who has done a Nintendo game before, and we haven’t worked in other companies, so we have no background.’”) Pina is diplomatic talking about these times, but something slips into his voice occasionally. Even amid his slightly awkward English, honed through years of console company liaisons and tech tutorials, his word choice betrays him. He isn’t angry about all of this; he is annoyed. Annoyed because he knew that his team could make games.

Pina doesn’t remember seeing a Nintendo Entertainment System before the mid-’90s, when other countries already had the Super Nintendo and the Sega Genesis.

Go further back in time and you can trace why these problems exist in the first place. Pina cites the poor economy after the revolution. (The Carnation Revolution happened on April 25, 1975, and was basically a nonviolent military coup against the longstanding dictatorship. It’s somewhat ironic that in a nation with a long history of conquering and being conquered, their latest uprising would be against themselves.) He remembers a childhood where the Sinclair Spectrum, a rudimentary 8-bit home computer, was popular in the ’80s, a weird alternate history to the one we know in North America. A local factory produced the Spectrum, making it much more affordable than early Nintendo and Sega consoles, which had to be imported. Pina doesn’t remember seeing a Nintendo Entertainment System before the mid-’90s, when other countries already had the Super Nintendo and the Sega Genesis. Not only was the Spectrum much cheaper, its games were too. A Nintendo cartridge would run you the equivalent of 40 euros. A Spectrum cassette? Three. Even still, they were heavily pirated. Making games just wasn’t something you could make a living at. While studios in England, France, and Spain grow and flourish to this day, Portugal’s gaming sector never got a chance to take root, even though Pina and his friends fell in love with creating games on their Spectrums.

As Pina and his small team have struggled to make their own games on their own terms in their own country, they’ve seen their friends go elsewhere. They’ve seen them snatched away by Ubisoft (France) and Crytek (Germany). They’ve watched their friends quit gaming altogether and work in the software industry creating mind-numbing piecemeal work, or quitting that and getting a job in a factory. They’ve done it knowing that if they failed, there was nowhere else to go. There are no other companies where they can bring their resume: they’re the only game in town.

So it makes sense that Pina is so frantic, so protective when he talks about his first game, Sudoku for Kids, a title that doesn’t inspire thoughts of greatness. But in 2006 it came after years of failing. Most of the staff quit after their shooter based on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Holy War, had been rejected by everybody. “Take-Two publishes Grand Theft Auto so they should have no problem publishing a game about the Israeli-Palestinian war. Of course they laughed. A lot.”

Filipe, Jeffrey, and Bruno quit too. Pina went back to working in television, while Jeffrey and Bruno started working for a software company. Pina eventually got back into things, unwilling to leave his country and unwilling to do something he didn’t particularly care about. Working on a piece of casino software by day, they banged out Sudoku for Kids in three months. The game isn’t as important as the fact that they’d finally done it, after a long history of failure that was out of their hands.

Pina explains this, sneaking glances at his computer monitor every few minutes.

There are no other companies where they can bring their resume: they’re the only game in town.

He is understandably anxious. The PlayStation Network breach in April delayed the release of Seed Studio’s real-time strategy game Under Siege to June 2. It’s been three years in the making, their biggest game yet. It’s also the first next-generation console game to come out of Portugal. These days the studio has expanded, and there is more at stake. Students fresh out of school knock on the studio’s door, resumes in hand. Pina admits it’s overwhelming, but he’s glad to have created an option for future would-be developers. He’s not especially worried about how well the game sells—he’s started from scratch before—but he’s afraid that the next time a new studio tries to set up shop, it won’t be taken seriously. He remembers the frustration dealing with bankers, trying to get a loan. “They don’t understand. And if they say, ‘Show us a product where this has worked’ and you say, ‘No, there’s none’—they say, ‘Oh, so it’s never worked?’ No! It’s just nobody ever tried!”

“I prefer a thousand times to have all these problems, but to do our own things,“ says Pina. “It’s not healthy. It’s very nerve-wracking, but, again, it’s much more gratifying doing it. If Under Siege doesn’t sell as much as we’re hoping, the company can close doors, of course, that can happen. But at least we tried it. We did it, as Frank Sinatra put it, our way.”

He steals another glance at his screen.

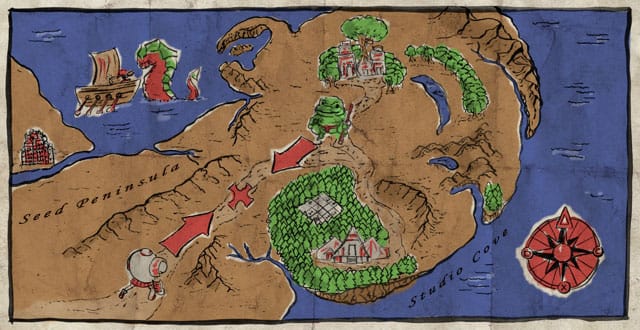

Illustration by Daniel Purvis