Making sense of the endless reflections of Her Story

“My name is Hannah. H-A-N-N-A-H. It’s a palindrome. It reads the same backwards as forwards. It doesn’t work if you mirror it though, it’s not quite symmetrical.”

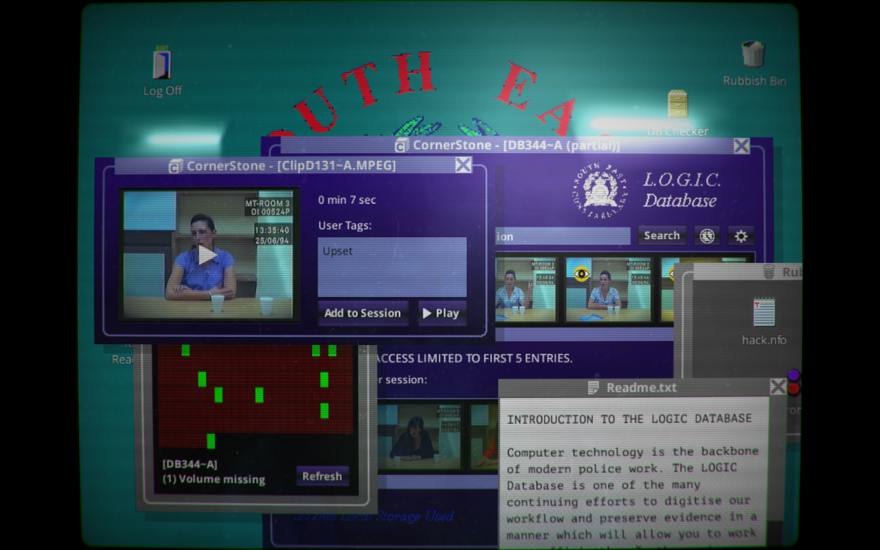

That’s how Her Story begins. At least, how it begins chronologically speaking. After saying yes to a coffee (black, no sugar), this is the second line spoken by Hannah in her interrogation. When you played, though, chances are this wasn’t the first, or even second, clip you watched. The game is constructed out of hundreds of clips like this, which can be viewed in any order depending on which search terms you pick.

It’s also the game’s first lie. Because this isn’t Hannah, after all, but her identical twin Eve. E-V-E, another palindrome. Between each of the seven interviews, the two women alternate in a neat symmetrical pattern: E-H-E-H-E-H-E.

Their lives follow a similar symmetry. Separated at birth, they grow up on opposite sides of the same street. Sleeping with the same man, both get pregnant from their first time with him.

In between, they constantly swap places, so that Eve can pass as Hannah. Eventually, deciding to become their own people, Eve disguises herself with a blonde wig. She meets and seduces Hannah’s husband, Simon, without him realising they might be twins. Finally, the whole thing is inverted as Hannah wears the wig and tricks Simon into thinking she’s Eve.

Laid out flat like that, unpicked from the tangle of videos, Her Story‘s narrative looks too neat. Their stories hinge on a disguise that would make Clark Kent blush, an ability to fool their own parents that’s straight out of The Parent Trap. Against the naturalistic trappings of Her Story‘s presentation—the found footage presentation, the loose chatty dialogue—these contrivances can chafe.

Her Story‘s narrative looks too neat

It’s almost easier to believe that the whole thing is a fiction Hannah is spinning, that “Eve” is just a figment of her imagination. Her Story constantly toys with this idea. Talking about his affair with Eve, Hannah says “Simon wasn’t seeing another woman.” You get the impression that, the way she sees it, she’s telling the truth. Talking about the first time she saw Hannah, Eve says simply: “She was me.” And given that this is a twist-filled murder mystery, you have to ask: is that metaphorical, or a literal plot point?

“They’re the same person”’ is the kind of plot twist that would be applauded in 1994, when the game is set. In 2015, it’s faintly embarrassing, both as a plot device and a representation of mental illness. Fortunately, I think the game actually goes out of its way to contradict this reading of its plot.

When Eve is hooked up to a lie detector, she tells only one lie: “My name is Hannah Smith”. Which could still mean that “Hannah” that is a figment of Eve’s imagination, except for the tattoo. Eve has a tattoo—an apple and a snake, representing clunky symbolism—which appears and disappears between interviews.

That leaves the other explanation: that these neat coincidences are just a function of this being a story—and in stories, patterns are inevitable. They’re how we make sense of the world and our lives, and Her Story demonstrates that process repeatedly.

As interview subjects, Eve and Hannah pick and choose events to make themselves look innocent. As children, they turned to stories written by others. “Fairy tales. Stories about lost princesses. Evil witches. Magical mirrors and lost children,” Eve says. “So you see, even before I knew the truth I’d found it in those stories.” It’s not hard to see why.

In these stories, Narcissus falls in love with his own reflection. Alice falls through her looking glass and into another world. In Snow White and Hans Christian Andersen’s The Snow Queen, wicked queens draw their knowledge from magic mirrors.

Meanwhile, Hannah and Eve fall in love with each other, their own living reflection. Together, the two use stories to escape the troubled circumstances of Eve’s upbringing. Learning about life from a book of fairy tales and a television obsessed with Princess Di, they identify themselves as princesses.

Hannah and Eve fall in love with each other

It’s worth noting that, with the exception of Narcissus, all of the stories named above are about women. In her essay Book as Mirror, Mirror as Book, Veronica Schanoes points out “the historical association between femininity and the trope of the mirror,” particularly in fairy tales.

Schanoes also discusses the long tradition of Eve—the biblical first woman and humanity’s first sinner—being portrayed looking into a mirror. “Eve’s connection with mirrors suggests the medieval emblem of vanitas, always depicted as a woman gazing at herself in a mirror,” she writes.

In Her Story, Eve—the first twin to appear on-screen and arguably the first to sin, by sleeping with Hannah’s husband—presented with a set of psych-test pictures, Eve can’t help but see herself in them. In the first, she sees Rapunzel, and describes a girl trapped, “looking out the window because her mother won’t let her out.” In the others, she tells tales of mistaken identities, affairs and women wielding sharp objects. It’s practically a full confession.

Seeing ourselves isn’t sinful behaviour, though, it’s human. We do the same thing when we play Her Story. The game presents us with chaos—271 video clips which can be accessed in any sequence—and asks us to draw an orderly narrative out of it.

The computer we use to do this is functionally a magic mirror, albeit one running Windows 95. The screen transports us to another world. Provided with the correct search terms, it can provide us with all the knowledge we need. So we use our own experience of the world, and of similar stories, to ask the right questions.

But ever-present in the fuzzy glare of that screen is another reflection, like the smudge of a supposed ghost in an old photograph. Occasionally, there’s a flash of light and the reflection comes into focus, so you can nearly make out the face—and it’s not yours.

The very end of the game reveals the identity of that person: Sarah, the second of Eve and Hannah’s pregnancies, the daughter they didn’t want to call “Ava” because it’s a palindrome. For all you’ve had to put yourself into the game to solve its mystery, it turns out this was never your story. It was always hers.