Map slippage is real, and it’s about to matter

If an object does not exist on a map, does it exist at all? Do you? You can see it with your own two eyes, and yet it is exists outside your world.

In the early days of mapping, when much of the world was unknown, such discoveries simply expanded the known universe. There was a world beyond maps. But now that we go through life with the reasonably well-founded belief that maps can accurately capture the intricacies of our world, the process of mapping glitches raises a whole new series of problems.

When this happens in a game, it’s almost funny. In Halo 3 (2007), for instance, a Monkey Man existed outside a level map. The only way to reach it was to die and be reborn in a convenient locale. It was a glitch, to be sure, but it was hardly consequential. Indeed, these sorts of videogame mapping glitches populate obscure forums as weird collectibles in their own rights; mapping failures to be discovered (and, in some cases, remedied) by intrepid explorers.

The Halo 3 glitch was not all that dissimilar from the first famous internet mapping glitch. In the early days of Google Maps, if you asked for driving directions from an East Coast city to London, you were directed a specific pier, and then told to drive across the ocean. For those who were in on the joke, it was a delightful little Easter egg. For those who weren’t… well, who knows? Here’s hoping they didn’t take it too seriously.

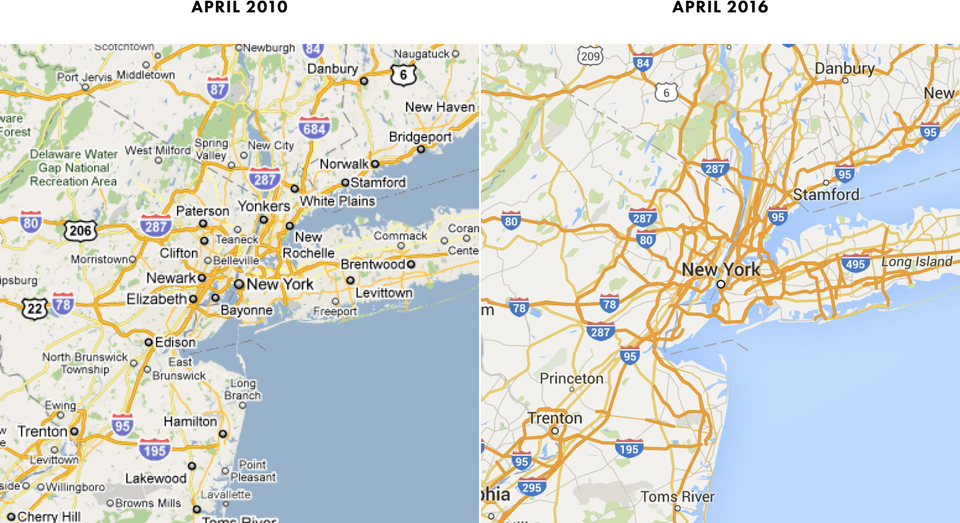

Maps are more serious now. Perhaps they always were, and the public is just catching up. Google no longer tells you to drive into the sea, but as Justin O’Beirne pointed out in a recent essay about the evolution of the company’s mapping product, “the number of roads shown has actually increased.” He further noted that the placement of text in relation to labels had been standardized and fewer cities were displayed. This, one supposes, is what adulthood looks like.

infrastructure would eventually grind to a halt

We are now very much in the adulthood of geographic data. Just turn on a new phone and watch it be inundated by apps’ demands to use your location, some of which make more obvious sense than others. These uses of GPS, it should be noted, are but the tip of the iceberg. “There are now around seven G.P.S. receivers on this planet for every ten people,” Greg Milner, the author of Pinpoint: How GPS Is Changing Technology, Culture, and Our Minds, noted last week in The New Yorker. “Estimates of the system’s economic value often run into the trillions of dollars.”

As with all systems that are this valuable, the real questions involve what would happen in the event of a failure. In the event of a breakdown, Milner notes:

The Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency recently determined that, within thirty seconds of a catastrophic G.P.S. shutdown, a position reading would have a margin of error the size of Washington, D.C. After an hour, it would be Montana-sized. Drivers might miss their freeway exits, but planes would also be grounded, ships would drift off course, commuter-rail systems would be tied up, and millions of freight-train cars with G.P.S. beacons would disappear from the map.

It’s hard to know exactly what to make of these warnings. As the pilot-cum-journalist William Langewiesche once noted in The Atlantic: “Air-traffic control’s main function is to provide for the efficient flow of traffic, and to allow for the efficient use of limited runway space—in other words, not primarily to keep people alive but to keep them moving.” Planes, in other words, would be able to coordinate and land, but they wouldn’t take back off. The same holds true in other cases; drivers can navigate cities when traffic lights go out, but they are unlikely to plan further sorties. Milner is not wrong in pointing out that some drivers would miss their exits and that infrastructure would eventually grind to a halt, but immediate and widespread apocalypse—in spite of the speed at which GPS could fail—would be unlikely. Rather, the damage of infrastructure grinding to a halt that Milner alludes to would have a longer tail and speaks more to the importance of geographic data in the current economy.

That, in turn, brings up the second cause for concern raised by Milner: spoofing. Sending false signals over a short distance could conceivably affect certain devices. To wit, Milner notes:

Security officials have been concerned about the susceptibility of G.P.S. to spoofing since at least the early two-thousands. Fourteen years ago, a team at Los Alamos National Laboratory, in New Mexico, built a spoofer by modifying a G.P.S.-signal simulator (a legal device that tests receivers’ accuracy) and aiming it at a stationary receiver more than a mile away. The receiver’s display revealed that it believed it was zipping across the desert at six hundred miles per hour.

Seven years before the Los Alamos test, spoofing GPS was central to the plot of the James Bond film Tomorrow Never Dies, wherein a British warship is slowly led off-course to provoke an international incident. Whether such a thing could actually happen is not really the point; Tomorrow Never Dies introduced GPS spoofing into the cultural vocabulary. It was, one must also note, a movie where a “stealth ship” remained invisible because, on multiple occasions, people relied solely on GPS instead of, say, looking out a window at a ship a few hundred meters away. (More on that in a moment.)

autonomous vehicles would crash into one another or living rooms en masse

The fear of spoofing, mind you, presupposes that the streets and locations we see on maps are accurate. This, though we don’t like to talk about it, is as much an article of faith as it is an objective truth. In China, Geoff Manaugh wrote in a recent article for Travel and Leisure, “every street, building, and freeway is just slightly off its mark, skewed for reasons of national and economic security.” In order to make a digital map in China, he notes, one needs government permission, a condition for which is the inclusion of a random offset in coordinates. “The result is an almost ghostly slippage between digital maps and the landscapes they document,” Manaugh writes. “Lines of traffic snake through the centers of buildings; monuments migrate into the midst of rivers; one’s own position standing in a park or shopping mall appears to be nearly half a kilometer away, as if there is more than one version of you on the loose.”

In most cases, this is just a strange edge case—something larger and more systemic than a glitch but also not much bigger than an inconvenience. (The random offset can be accounted for, but that requires expertise a layperson doesn’t have.) In marginal situations, however, 100m of variance in one’s location can have serious consequences. “If a traveler finds herself in, say, Tibet or on a short trip to the artificial islands of the South China Sea—or perhaps simply in Taiwan—are she and her devices really “in China”?” Manaugh asks. Strange things can happen when the borders experienced by humans and devices cease to overlap. (This, once again, is the plot of Tomorrow Never Dies.)

The various problems with mapping Milner and Manaugh raise are of this moment because the “look out your window and communicate”-solution suggested by Langeweische and known to drivers in the midst of power outages—though not the captain of that ship in the Bond movie—may have reached its limits. A self-driving car’s mental map of the universe, for better or for worse, is not the same as a human’s. It’s unfair to say that, in the event of a GPS failure or slippage, autonomous vehicles would crash into one another or living rooms en masse. At the same time, however, many of the advantages of autonomous technology, such as the ability to pack vehicles closer together would be much more affected by an outage.

As in Langeweische’s aviation scenario, vehicles wouldn’t immediately crash, but the system would (safely) grind to the halt. In a world where more devices depend on GPS and downplay the importance of human input, gaps between the borders experienced by humans and technology can be highly consequential. Indeed, one might even wonder which of these two geographic realities might be dominant.