Mario & Luigi Paper Jam Bros. folds in on itself

There’s something strange—maybe even broken—about fetishizing materiality in a digital world the way Mario & Luigi Paper Jam Bros does, though it’s not the first game to do this. I first noticed this in another Nintendo game from last year, Yoshi’s Wooly World, which trades on a contradiction. It’s a game about adorable dinosaurs in adorable environments made out of yarn and glue. Aesthetically, it’s “crafty,” which we value precisely because of its irreproducibility. Flaws aren’t flaws in this context; they’re signs of the hands that made it. And yet videogames are bits—0s and 1s—all the way down: data perfectly, inhumanly copied onto disks and shipped worldwide in order to connote this experience of the handmade in a medium that all but disallows it.

I think there’s a case to be made that Mario & Luigi: Paper Jam Bros. continues and complicates Nintendo’s meditation on materiality in the virtual.

As its title implies, Paper Jam is effectively a crossover episode for two once-independent Nintendo series: Mario & Luigi and Paper Mario. There’s an odd history of convergence and divergence hiding in this crossover. Mario & Luigi and Paper Mario, Nintendo’s Mario-universe role-playing games, inherited different aspects from their progenitor, the still-excellent Super Mario RPG (1996). They split up some elements of Super with the releases of Paper Mario (2000) and Mario & Luigi (2003), putting the the party-building system in one and the battle focus in the other. What was once whole, then divided, has now come back together.

In light of this, I feel obliged to include the deeply cynical reading of this reconvergence: Crossovers are a bit like shotgun weddings. They bring together two different groups of people in the hopes that they’ll have fun because (or in spite) of the circumstances that brought them together. But recourse to the market logic underpinning a work of art is both too easy and less interesting than almost any other reading. So, instead, let’s talk about Paper Jam and the question of “the real.”

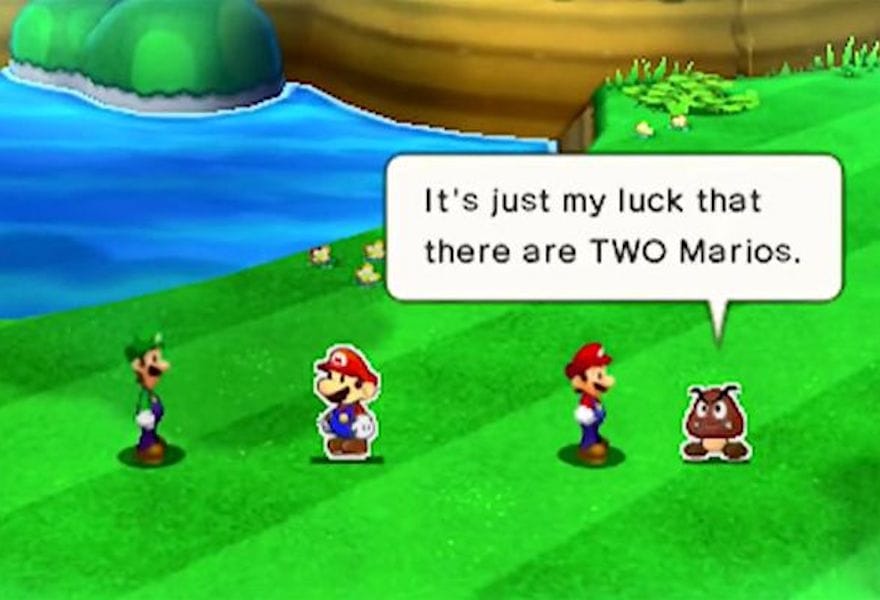

Luigi’s only character trait—unrelenting, ill-founded terror—catalyzes the plot of Paper Jam. A book containing all of the stickers from the Paper Mario series falls on the floor, breaking a spell of one sort or another placed on it, and, whoosh: Demons unleashed upon the world.* But with the demons comes some good, too—namely, Paper Mario, Peach, et al. The main social conflict that you encounter as the worlds of Mario & Luigi and Paper Mario collide is not language or history, but dimensionality. After overcoming the strangeness of entering a world with an extra dimension, there exists this marker of difference that fundamentally changes how characters encounter and interact with the world. Consider the layers: there are the paper characters, who are physically 2D but have been thrust into a 3D world; there are the 3D characters in a 3D world destabilized by the exposure of the 2D world within it; and then there’s You, some n-dimensional being controlling the temporal fates of these characters (not to mention their perceived dimensionality, depending on how much you mess around with the 3DS’s 2D/3D slider). This dimensional confusion is doubled by the fact that all of the major characters have literal doubles: two Peaches, two Marios, two Bowsers, etc. Most importantly, this isn’t new; the thematic has been under exploration in these games since at least Super Paper Mario (2007), and perhaps most memorably in A Link Between Worlds (2013).

Crossovers are a bit like shotgun weddings

So. We could try to tease out these cross-dimensional Dostoevskian doublings, but I think that risks giving credit where credit isn’t due. The conflict between materialities is what Paper Jam really adds to the mix. Not only are there several matryoshka-nested dimensions, but these dimensions are actually made of different things: paper and the matter of the 3D (“real”) world. “Paper jam” is in many ways the perfect conceptual metaphor for this encounter and deformation—a paper jam happens when a (roughly) 2D object is mangled into 3D by that awful printer that you really, really need to replace. Changing dimensions, it ceases to function in the way we expect paper to.

There are cultures of difference that arise out of this conflict. 3D Toads deride 2D Toads, while 2D Toads do things the 3D ones could never do, and deride the 3D Toads in return. Bizarrely, this might be read as a first pass on Nintendo’s part at representing a mutually constitutive diversity rather than a conflict of cultures, an issue that the company has relegated to speciation (Animal Crossing) or player design within highly circumscribed bounds (Miiverse). Of course the dimensions wind up needing one another to survive, collaboration triumphs over dimensional difference, etc. The origami sections are perhaps the most literal invocation of this idea, with the 3D characters shaping the 2D ones in their image in a gesture that is both collaborative and colonizing.

Material and the diegetic real come into interesting conversations throughout Paper Jam, but that is the reach of the game’s ambition. As with many Nintendo games of the last few years, its gameplay elements are immaculately designed but risk nothing.

///

* Footnote: It’s worth noting here that this plot is structurally fundamental to tons of Nintendo series. The fact that the world changing instigates the quest betrays the pseudo-conservative impulse underwriting these games: scary ideas come flying out of books, become unchained from their deep chambers in the earth, or arrive from outer space, and it’s up to the Valiant Youth—the next generation—to suppress the Bad Thoughts and restore the world to The Way It Was Before. Hence the conspicuous absence of history across games that take place in series in a fundamentally unaltered world—they’re always starting from the same point in social history that was checked by the hero in whatever previous attempt at insurgency, revolution, etc. instigated the previous game. Granted, this is not to say that it would be better for “evil” to win (I imagine Ganondorf has a rather poor tax plan), but just to ask: Has there ever been a monarchy kept in power by suppressing all attempts to change its kingdom that we would also cast as politically was also politically neutral or even “good?”

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.