This article is part of Mario Week, our seven day-long celebration of the 25th anniversary of Super Mario World and 30th anniversary of Super Mario Bros. To read more articles from Mario Week, go here.

///

When I was four, I used to sit by the window most evenings, pressing the pads of my fingers to the glass with my face set in an intense look, watching for my dad to return from flying. The moisture from my skin left a white outline of my forehead and fingers which, in winter, grew complex with frost. Dad kept such odd hours that I was often up till bedtime, eyes scanning the parking lot for his car or familiar pilot’s uniform. When I spied him I would leap up with a shout, scramble to the front door and tumble excitedly into his arms like some blonde fury.

Sometimes Mom would leave us to go out with her friends, and Dad would be left to take care of us. It was always dumplings and gravy or packs of chicken-broth ramen, which we loved. Sometimes we’d go on walks up to the crown of Albuquerque mountains or shoot bb guns out in the hills. We’d go to air shows. But most of what I remember involved us two spread out on the grey carpet of the living room floor playing Nintendo. The NES was a carefully regulated commodity in our household, locked tight in the master bedroom closet every day except Saturdays and Sundays, when Dad would bring it out with a magician’s swagger. Every time it had to be stowed was a minor tragedy.

“Can we play it more?” I’d ask.

Mario was our favorite, of course. Top Gun was disorienting and confusing, and it was too easy for me to cheat with the orange sharp-shooter from Duck Hunt; all I had to do was wait till my dad turned his back or checked on my brother so I could press the nozzle of my gun to the screen and shoot the birds point-blank. This typically resulted in an unpleasant shock and ozone smell. And of course it always felt better to land a three-hit streak while Dad was watching than to knock out 10 with him gone. With Super Mario Bros, we were always playing together.

He treated the system like a holy relic

I always liked the gold seal of quality stickers Nintendo put on their game boxes. Was it just my memory, or were they always embossed gold? As a kid I’d thumb the corners and cardboard edges of a new box, then pull the cartridge hot out of the NES dock and smell the toothy plastic, all ionized from loading up sprites and music. But I never understood what Nintendo did for the gaming industry. After the gaming market crash of ’83, Mario was some kind of messiah of branding: a hero built in-house, simple and easy to pick up and play, approachable. Even the way Nintendo streamlined the NES to look less space-age than its Japanese forebear, shying away from the word “game” in favor of “entertainment system,” in a calculated move to engender trust in the American public.

My dad waited several years after the console’s release to buy it half-off at our local Wal-Mart in a compulsive yet frugal moment of weakness. He treated the system like a holy relic.

“Don’t lick the cartridge,” he told me.

But wasn’t the reason anyone bought an NES to play Mario? (And maybe Duck Hunt.) Dad and I booted up Super Mario Bros and played for hours, switching off between Mario and Luigi. At four, my reflexes were shit, but my dad was a good sport. And even though I died senselessly, in pits and on the same koopa and sinking off the bottom of the screen, I eventually got wise. And I had something my dad didn’t have: a network of correspondents I’d meet during recesses and children’s church.

“Jump off the elevator in World 1-2 and you’ll find some pipes that’ll let you skip some levels,” they told me. I remember the surge of adrenaline when I led my hobbling avatar to the portals, the look of surprise and admiration on Dad’s face.

///

I have easy memories of reclining on Dad’s back as he played belly-down on the floor, my legs hiked up on his shoulders, as I would broadcast every detail on-screen to him: every spiked shell or stray bullet. Sometimes I’d fall off to the side, so excited, and gesticulate wildly when he caught the top flag at the end of a level. Once we found the second warp gate, our play sessions became more intentional, more labored—like the point in early adolescence when sports turn serious. If we finished the game, we’d have more than bragging rights: we’d have achieved something together. We never beat the game, but we got damn close.

One Sunday after church, I saw the cover of Super Mario Bros 3 on display and nearly burst into tears with excitement, tugged on Dad’s sleeve. There was another Mario, and didn’t he see it? Could we buy it? This was obviously a purchase Dad had been trying to avoid for some time, as the game had been out for years. My parents were still young and money was tight.

“Ask your Mema for it,” he said. It was my birthday in a few months, and to my young mind there was nothing my grandparents wouldn’t do. I remember coming home afterwards and calling Mema on the phone, politely rambling about how I’d seen Mario at the store, and would she please buy it for me on my birthday, my fifth birthday when she came to visit us in Albuquerque, and I loved her so much. When she said yes, I dropped the phone and said a hundred thanks.

When I finally unwrapped Super Mario Bros 3, the game had become my world. Playgrounds were full of lava, and when we played tag, you weren’t it; you were a koopa. Dad and I tore through the first world of the game, fled from the angry sun, explored the water stage. Although we were playing just for fun, the gaming took on its own urgent timbre with a new kind of time limit: in a year and a half, we’d have to leave the NES behind.

///

“How do you feel about moving to Indonesia?” Dad asked, half-joking. After he showed me Indonesia in the atlas, I crossed my arms and shook my head.

“Let’s not go there.”

“It’ll be really exciting!” he said. “Think of it like Indiana Jones. Or Mario.”

My parents would not be convinced otherwise. With surgical precision, I constructed a strategy for how to take advantage of every cheap shortcut in Super Mario Bros 3 to finish before we’d have to move. Long weekend afternoons were spent perfecting each level. I even let my little brother join in, hoping the extra practice would help us win the game.

“You need the hammer to get the last warp whistle,” a boy told me as we huddled under the slide. “Also, you need the leaf to get the one in the first fortress.”

Even with all the practice we never got past the penultimate airship: a gauntlet of bullets, cannonballs, turquoise flames. My parents sold off our TV and packed up the apartment to go on a year-long road trip as they raised funds. The NES, orange light gun and Mario games were stowed in one of six sealed green barrels placed in dry storage for whenever we would come back. We loaded everything into the back of an old brown van smelling of melted plastic and took to the road.

///

They tell me I screamed as they took me aboard the plane in Los Angeles. After months of preparation, packing, careful planning, we were on the threshold of leaving America; I crossed my arms over my chest, planted both feet on the ground and shouted, “I am not leaving this country!” Dad had to pick me up, kicking and shouting, and carry me through the boarding gate onto the plane.

In my head, I played through every level in Super Mario Bros 3 that I could recall. My knowledge of the game was such that I would replay any misses without a beat, imagining the exact physics of a star’s bounce, the specific timing necessary to dodge the piranha plant in the third level, the exact degree to which I would slide on a certain platform in the ice world. In my mind I scored a perfect game on that long twelve-hour flight to Asia, in between meals and in-flight entertainment.

“I am not leaving this country!”

We moved into a cool aluminum-roofed house overlooking a picturesque valley stepped with rice paddies, and when we walked through the labyrinthine streets to school, my senses were overwhelmed with so many strange, powerful smells and sights: a street vendor frying up moths in a tinny wok, a bike laden with chips and sweets, a young boy being circumcised on a rocking horse. There was no reason to think of the Mushroom Kingdom or Mario or the Princess Who Was in Another Castle. The world in which I now lived was so completely alien, there was no escape.

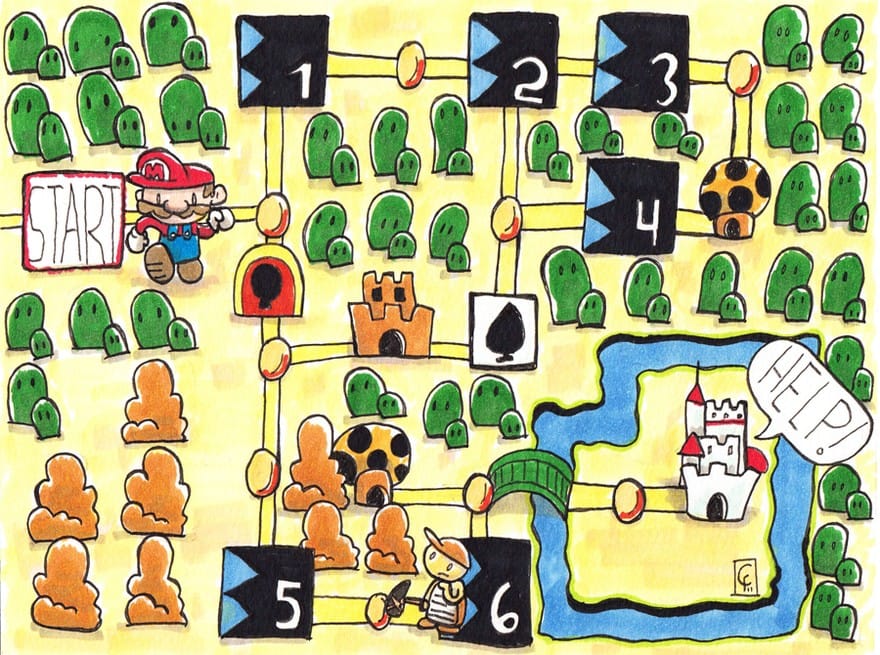

One weekend, we took a trip to a dormant volcano and I found myself nearly swallowed by quicksand on the shore of the hot springs. Later, in the spring, we went to Surabaya and explored the phalangeal tunnels and shafts dug by soldiers from World War II. When we returned home, my brother brought his Indonesian friends in and we traced videogame levels on construction paper, drew fake control pads, and pretended to play, since no one we knew had a TV. After watching my brother and his friends draw these levels out, I absconded with a pen and paper to my room and built another twenty levels from scratch, taping them to the top of the “game” so that they could be played through. Everything I could remember from Mario was incorporated: an angry sun-god, wicked turtles with fangs, ice cube castles. I’d made twenty-four levels before the novelty wore off, and the challenge was purely arbitrary, anyways. The “game-ness” of avoiding quicksand in my paper-system felt cheap after feeling real earth close around my shin like a hungry mouth.

Later, on another island, we lived by the ocean in a house with stilts. I spent a little time with Dad when he tried to teach me baseball or how to paint model airplanes. But like my memories playing games with him in another world, every moment I spent with him carried an almost untouchable quality, a mystery. There was part of him I couldn’t understand, and a part of me he seemed unable to relate to.

About two years after we’d moved to Indonesia, Dad took me flying early in the morning, buckled me into the copilot seat of his small bush plane and landed on a remote airstrip at the base of a mountain hemorrhaging yellow clay and mud. A few Dani tribesmen met us, smiling, on the runway, and led us up the molting face of the mountain to their village. The men carried bags of rice from the hold, a large boar, packets of medicine, while Dad carried me when the path grew too slick and steep for my young legs.

When we reached the top, all our shins streaked bright with mud, Dad set me down in the midst of a gaggle of dark-skinned Dani kids my own age. I remember the world around us was white and featureless with early morning mist, and the air was cool and wet so high up. In sync, with pronounced breaths, the children ran their palms up and down my arms, their fingers through my hair, sniffling from colds, gasping with curiosity. They’d seen pale-skinned men with hairy tanned arms before, but never anyone with white skin my age. I stood still, feeling strangely reverent, though I didn’t know why.

///

When Dad took us back to America, I felt different. Coming back, I was subdued and pensive, taking in the world the way one sips a slow drink. The world seemed grey and drab, somehow lacking; I found I had less to say to anyone, and the things people wanted to talk about were colorless and boring. So I took to games, to exploring Myst and Riven, anything that would let me slip into another world. I went over to my best friend’s house and slipped into the technicolor worlds on his N64. The console had recently launched, and Super Mario 64 was all that some of my friends would talk about.

“I know how to unlock Luigi,” one of them told me.

“How?” I asked. I’d never played the game, but I wanted to know all its secrets. The classmate fidgeted and described some complex cheat code and how you had to unlock 150 stars, which sounded like obvious bullshit. I nodded politely and asked if I could play N64 at his place.

I spent hours in the car playing Super Mario Land 2 in silence on my Gameboy while my brother did the same. When we discussed World War II in class, I wanted to raise my hand and talk about the time Dad and I had snorkeled out to the reefs at Nabire and wrenched scrap metal from a downed Japanese Zero. Nobody would have believed me. I would walk around in a haze, speaking a mixture of Indonesian and gibberish, hoping everyone would be so put off they’d leave me alone, and that someone might be so intrigued they’d ask what I was saying. Dad was so busy working extra jobs that when he came home, he seemed distant or angry; in truth, he was just tired. I woke up some nights from terrible nightmares, curled up in a ball in front of my parents’ bedroom door.

taking in the world the way one sips a slow drink

One weekend, our family holed up in a low-rate Ramada hotel room and rented an N64 and a copy of Super Mario 64 to play for a few days solid. I remember my rush of adrenaline when Dad plopped down next to me and watched me tackle, jump, kick in 3D: it felt like the old days. He grabbed the controller for a few levels, then gave it back to me. For whatever reason, the game didn’t take. Maybe it was Mario’s voice, the cartoon-world, the weird face-pulling. I tried to beat Whomp, the burly anthropomorphic slab of rock, hoping the drama might get Dad interested. Instead, he told me to wrap up in fifteen minutes so he could play Madden with my brother.

“I just have to finish the level,” I told him.

“Fifteen minutes.”

Years later, I booted up Super Mario Sunshine and waited for the old feeling to set in. The screen was populated with bright, bouncy characters, and Mario was rendered in high fidelity and had a talking waterhose for some reason. It was no less an acid trip than any other Mario game, but for whatever reason I just wasn’t feeling it. I was about to turn off the Gamecube when Dad came in, sat down and started watching.

“It’s the new Mario,” I said.

“Mario got weird.”

I found myself scrambling for some purchase, exploring the first world, trying to find something we could both enjoy, but it was just that: weird and pretty. The game seemed so removed, so unrelatable, like I’d seemed to those Dani kids who had never seen a blonde boy their own age. For the first time in years, Dad and I were equally matched in our apathy.

///

This past May, my boyfriend and I played through Super Mario 3D Land on a 3DS he’d scavenged from a stoner’s abandoned apartment. A whirring chorus of cicadas filled the air outside. I coaxed myself into the crook of his shoulder to watch the screen and coached him through the airship levels like a pro, even though I’d never played the game before. When he couldn’t beat the boss at the end, I fished the 3DS out of his hands and did it for him. Hearing the old chiptune dings, whoops and hoots drew me back to an old, safe place. We drank bourbon in hammocks to celebrate the win.

Months later, I drove Dad to Chicago under a heavy rain, locked in familiar silence. I wanted him to ask me about who I’d been seeing, even if it made him uncomfortable. I wanted to tell him about our trip around Lake Michigan and the crazy taxidermy museum we’d seen and the swarm of mosquitoes that chased us by the lakeshore. I wanted to tell him I’d been playing Mario like we used to, and it was still fun, and they’d made it fun weird, not just weird, and it was okay to like it again.

The grey curtain of rain pulled back to reveal a brilliant sky, and we still weren’t saying anything, and I wanted to put my hands on the sides of his head, like I had when I was three, and say, “Hey look at me,” so that he’d look at me like he used to when we were fellow players on the living room floor way back when.

///

When I was in high school, our family visited a white-sanded beach off the coast of Papua called Tanah Merah. I sat, cradling my spongy torso, legs crossed on the sand as Dad took my brother downshore to toss the football back and forth. I watched them play with a practiced intensity, feeling adolescent and unique. After a few minutes I strapped on a snorkel and flippers, took to the rolling surf, and paddled out as far as my courage would allow. Beneath me was a panoply of gaudy technicolor and alien shapes: brittle spinefish, rainbows of coral threaded with shimmering tengirri. The tide had receded, so I let my hands trail like ribbons beneath me, skimming the tops of the underwater forest until an anemone stung my right palm. The underseascape looked so utterly small and wide; I thought of how the world must look to Dad in the cockpit of a plane, flying high above clouds and mountains with everyone else so small below. Nothing else seemed so grand.

///

This article is part of Mario Week, our seven day-long celebration of the 25th anniversary of Super Mario World and 30th anniversary of Super Mario Bros. To read more articles from Mario Week, go here.

First image via Christopher Furniss. Final image via david_a_l