Mario Mu: Transforming Political Reality into Playable Space

Can games seep into the political, social, and cultural realms of life? Across projects that fuse game development, filmmaking within game engines, LARP (live-action role play), and more, Mario Mu interrogates this question. The Croatian-born artist now lives in Berlin, where he conducts research about games, labor, and memory and helps publish architecture books. After a career illustrating for commercial brands such as Doodle Jump and Gestalten, Mario continues his independent creative practice, with all projects he thinks of as ‘extended gaming platforms.’

Here, we speak with Mario about studying under Hito Steyerl, cancel culture, and how Trump is a game-maker.

What was your first creative impulse?

I grew up with one foot in Croatia and the other in Bosnia. There is this small town close to Dubrovnik on the Adriatic Coast, which is on the border between Croatia and Bosnia, so I was every day, basically, crossing borders between these two states, which was in the ’90s, when I was a kid. The political situation, at that time, was influenced much by Yugoslav wars.

There was a substantial cut between the heritage; between the knowledge from the past to the present. I had no idea about the past, but I had a lot of space to invent stuff. I had an urge to make narratives and worlds.

You have three fine art degrees. What did you get out of these programs?

I was fortunate to find a program in Berlin where I got into a class with Hito Steyerl, who was extremely supportive. There would be 200 people every Tuesday at the class meetings. It was a very, very dynamic environment with a lot of people talking with one another.

When I studied a very classical painting approach, I worked with commercial video game companies, brands like Doodle Jump, SpongeBob, and Adventure Time. I would go to the university from 9:00 to 5:00 or 6:00. Until midnight, I would work on these video game projects. I wanted to get in more of the liveliness from video games into my practice. Why did everything have to be so tense, so uptight? These two experiences, studying painting and supporting myself as an illustrator in the games industry, made me want to fuse both perspectives into one focal point.

How does thinking in terms of ‘gamification’ inform your creative practice?

Gamification is the idea of implementing game systems and game tools in non-gaming environments. How can game tools be incorporated in military practices, in education, in science? And in my recent research, how are labor conditions gamified with broader, globalized, neoliberal-driven economies?

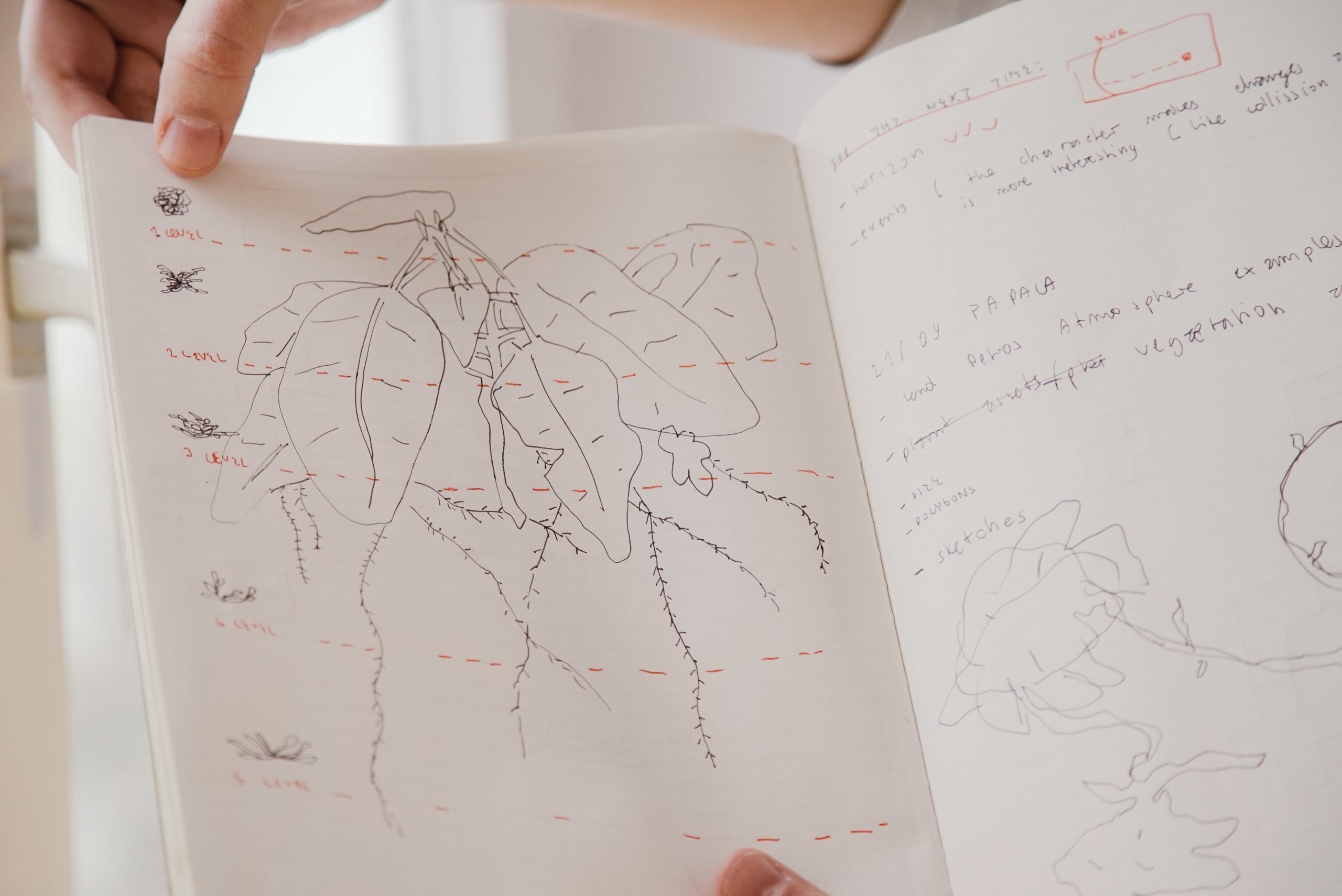

My first response was a project called Walkthrough. This was a continuation of my graduation piece, and a breakthrough for me. The basic idea was how can a group of people, how can they share one character? Usually, in video games, you have one event, and everybody has their avatar.

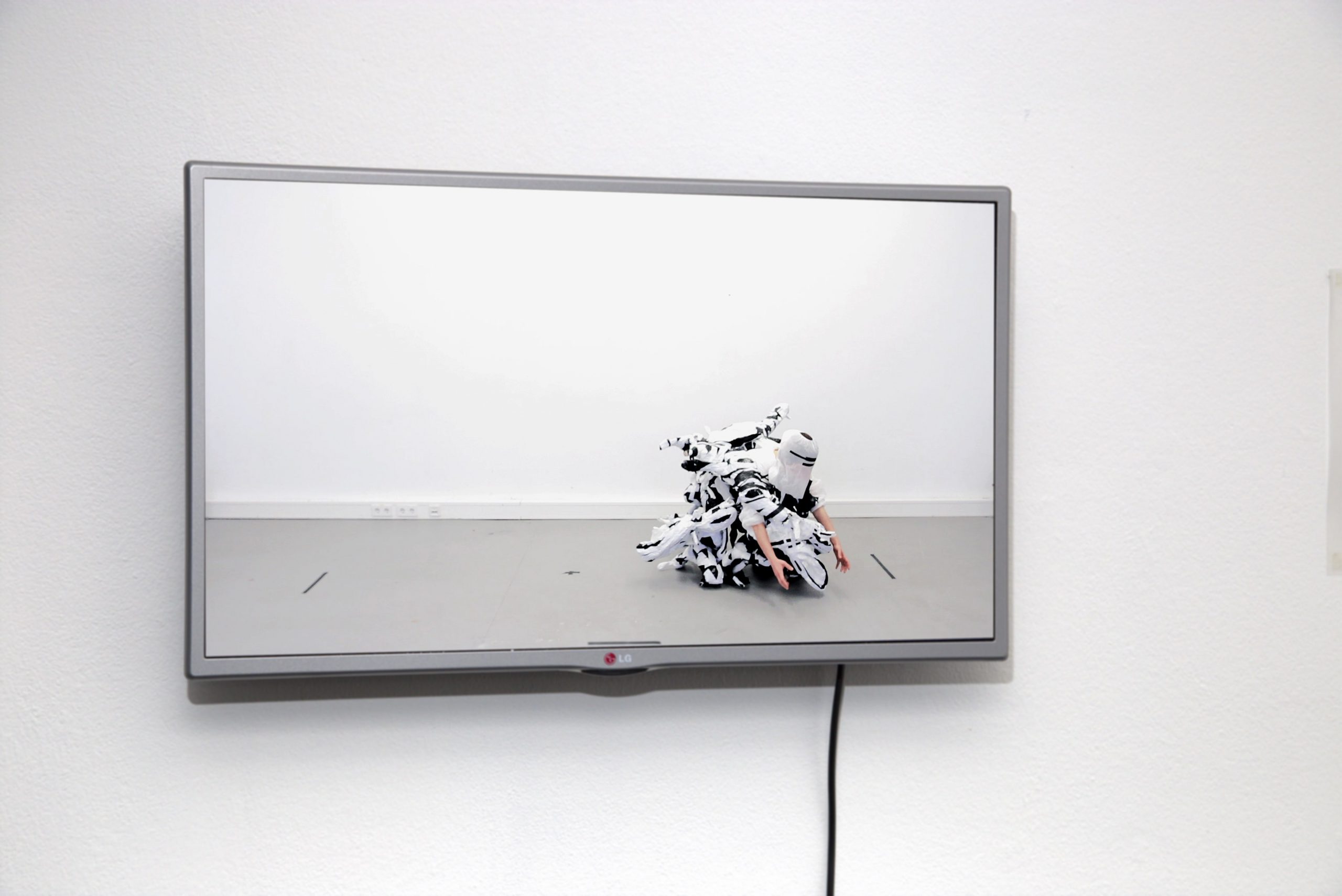

How can a group of people share one character? What are the implications, what are the consequences of this when everybody shares the same history, responsibility, and one body? We worked with 20 people over a few months. I made a straightforward costume, which was malleable and could be tailored to anybody. They could put on it how they felt most comfortable. After using it for a while, and they would leave it, and then somebody else would take over. With every use, a specific history would be impregnated with certain movements and experiences. I documented these changes, which resulted in an animation. What they left is something that feels non-human… a transforming body with a shared history.

You create projects that are considered LARP (Live Action Role Play). When you’re designing the structure for these, how much scriptedness versus randomness do you work with?

Prosthetic Animals was the first project where I would go to people’s homes, and we would find stuff around their house, and make a costume out of it all. The idea was, how can you you think or believe with your environment? It was based on research about habitat. How does your environment influence your behavior, and how can you approach a context that defines you differently?

My approach is similar to improvisational theater and role-playing games, but stripped of the fantasy. It’s more recontextualized. How can we use role-playing, for example, in dealing with trauma, in fighting oppressive systems? All of my projects inspired by LARP share one similarity—the idea that nobody knows what is happening. In all my projects, participants are constructing the whole story together by sharing their experiences with others.

The idea is to allow each character to embody a fragment of a broader experience. It’s about designing a game, so the characters interact to fit the whole narrative and come to their conclusions. A fascinating aspect of LARP is giving people so much freedom that they start to think laterally, think out of the box.

They speak for themselves. They have to present. They have to perform. Mostly, I make characters that all have some kind of a failure with them, so you have to have empathy towards that character, and then you are more relaxed, but this is the idea: Fragmented experiences, and having a game designed to have those experiences connect, intertwine and make the broader story. It’s always about building up a communal character. Either it is a narrative, an experience, a history, or some kind of theoretical framework for the future. In order to prevent escapism into fantasy worlds, we try to empower each other through the act of sharing imagination.

How did your research on cancel culture develop into your LARP-based project, Confessional Stage Diving?

I printed out news articles about canceled people, and this was your character. Before the start of the LARP, everybody would get the article, and they would read it, and they’d have to build a character out of that article. You have to bring in a lot of your information because there is not much given—what’s your gender, where do you come from, and more. So you are building your character immediately.

Before the workshop, people would communicate together, and slowly introduce themself to other people. Somebody else asks them questions and helps them to build their character. You have to invent quickly: “How old are you?” “I was born in the 19th century. I’m 200 years old.”

Sometimes, you didn’t know completely what you did wrong, or why you were canceled. Not all of the characters were canceled. Some were those who were the ones doing the canceling, and so on. All the different characters are interconnected, so to understand more about yourself, you have to find one other person who would help you understand a bigger picture. When you feel you know everything about your character, you go onstage to confess that story. There’s a detective element to it. Once you know your story, it’s like you are charged to have this emancipatory moment onstage.

When you’re executing a project or event like Confessional Stage Diving, do you have expectations for what’s to happen? Do participants defy your initial expectations?

I was a part of the punk and hardcore scene when I was a teenager, so this is where my fascination with stage comes from. Of course, nobody was forced to stage dive. There is an essential element of consent that nobody gets hurt and that we do it as comfortably as possible.

Once you’re onstage, you’re expressing your character. Here is your whole history, the entire sea of knowledge, which is forming, which is very, once when you have it, a figure, a form, elusive knowledge, understanding, you go out as a part of the bigger element, and jumping in as a way of sharing. This is what I was expecting or hoping—that people would take that into their body and run and jump into the crowd, and then the group gets you.

Empathy is important in LARP. It is our way to get out of our own body and understand others. The human capacity to empathize with others helps us grow. LARP is this exchange between fragmented experiences and the more overall experience, which is sometimes also abstract.

You think of game engines as an ecosystem, how all these moving parts are working together. How did you come to that kind of metaphor as a way to explore your practice?

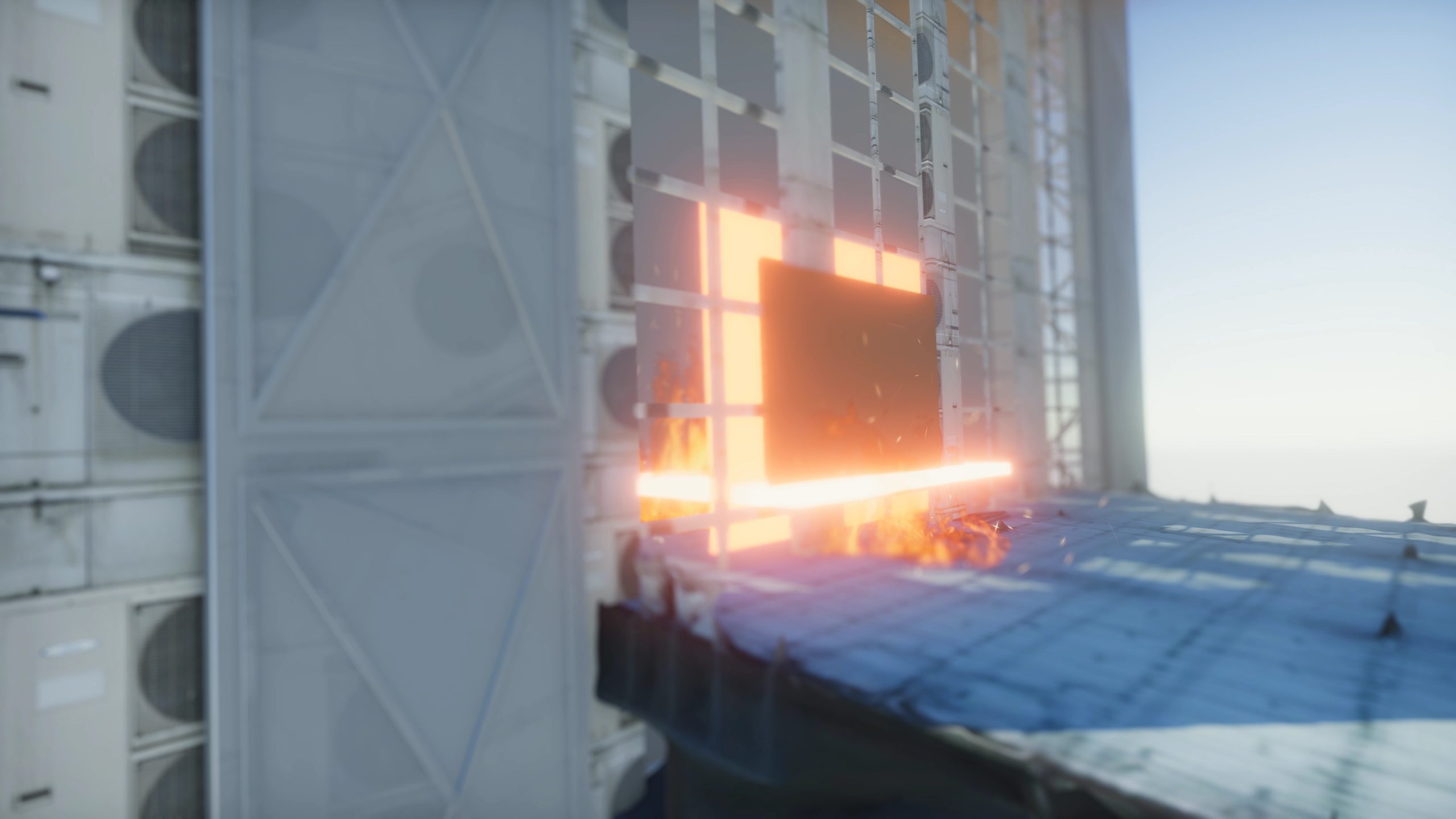

I use the idea of an extended gaming platform—a platform that uses elements of video, theater, choreography, drawing, sound. I’m interested in the idea of a human-built environment. How do people change their setting according to their own needs? This is also my interest in architecture comes from here. What is the infrastructure? What are the support systems for certain types of behavior?

It’s not about just video games. It’s never about sitting, and playing, and getting into this interactive cybernetic feedback loop. It’s more about: Where do I sit? What is around me? Paying attention to your environment, in general, is just a good way to get out of your head. To think about ecosystems and the environment is always a good way to get out of our heads, our internal monologues, dialogues, and dramas.

Things like theatre and LARP can expand the social capacity of mutual understanding beyond the system that narrows down the human life to a career-oriented experience. How can we find other ways to nurture certain social rituals, which are important for us to be healthy? One individual cannot be healthy if the ecosystem is not healthy.

In societal dialogue, games and play are not taken super seriously. But artists like yourself are combating this and think political and social issues through game systems. Can you talk more about this intervention you’re hoping to make?

I can give one example—the storming at the U.S. Capitol. Memes have circulated depicting the situation as bunch of LARPers storming this temple of democracy. The cosplay has become the method for the aestheticization of politics. It makes them believe that anything is possible if you put on a costume on yourself—you can even storm the Congress room.

This is where games and politics can get in a powerful collision with responsibility. Just because those people wore costumes, are they willing to accept the consequences and take responsibility for their acts? What I see, for example, in American politics, is that people can do so much, but nobody takes responsibility for it. It’s about the limits of how far you can go in playing without the responsibility. For me, this is very important.

The “bleed” is a term in LARP and game mechanics when an emotional experience from the game takes over your real-life social experience. There is a lot of this bleed now happening. Then this rage bleeds out through people who are, unfortunately, likely in a miserable living situation. This rage is getting more robust and irrational. What happened at the Capitol looked like some kind of a video game environment. To me, Trump is a game maker. How Trump plays is he improvises how far he can go. He constructed one game, which I think is going to damage a lot in the long-term. He made certain conditions of behavior that people embody or feel free to repeat. It will take us a lot, globally, to fix this and establish a healthier way of communicating.

On the converse of that, what do you see as the potential of gamification?

Games should not be just escapism. There is not enough conversation about games, so they’re are seen as for white, male, nerdy teenager—a nightmarish world where very low energies are exchanged. In reality, it’s completely different.

The gaming industry is one of the biggest in the world. I’m sure that different experiences formed within gaming environments will also influence the broader social spectrum in the many years to come. I do hope that they will be different. I do hope that they’ll also get us to a healthier point than where we are now.

We are now in a position where we are forced to imagine new worlds, ways of being, ways of interacting and addressing environmental issues. How can we also focus on games as something constructive, which can open possibilities to express experiences where we feel oppressed? How to find the platforms to communicate, elaborate, share experiences, and what to do with this planet. What can we do together to get this planet to a healthier and more sustainable point of being?

Credits

Interview conducted in January 2020. Edited and condensed for clarity. Photography by Laura Vifer.