“Good lord.”

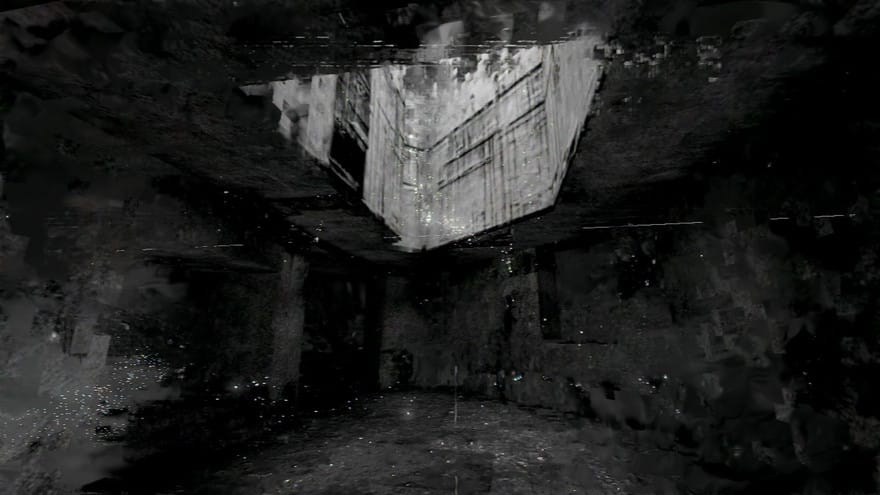

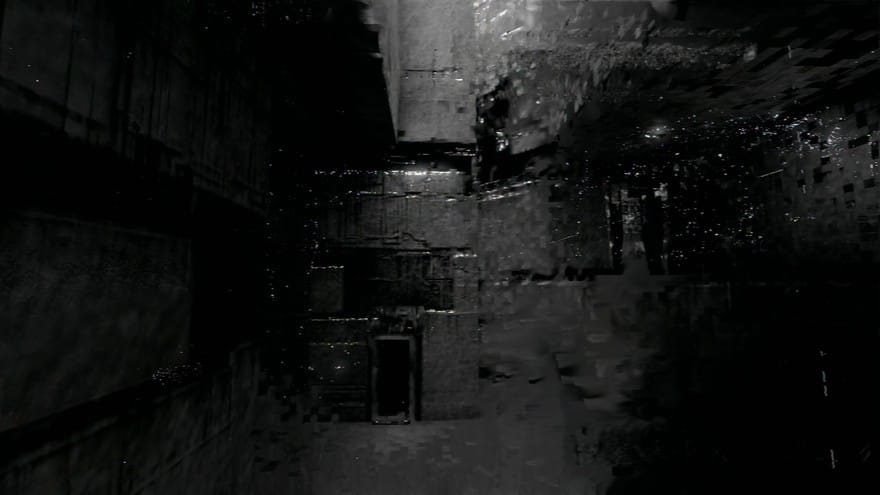

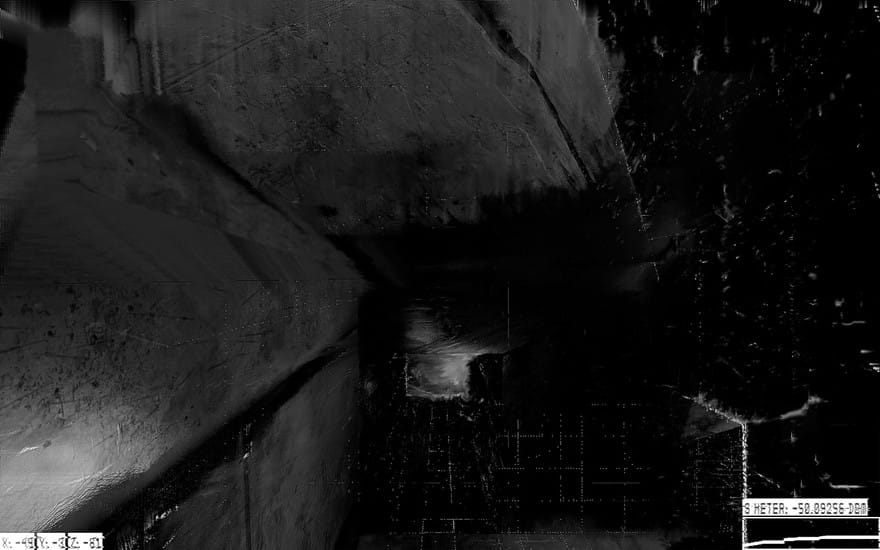

This is what I said when the game designer XRA kicked on Memories of a Broken Dimension, a game that’s been around for almost four years and that I’ve farted around with dozens of times in that span, and I said this—”Good lord”—because I felt it: a punch in the gut. I’d spent the past couple of days doddering around the Game Developers Conference strapped into various headsets and nodding politely through various demonstrations, and Memories of Broken Dimension was like a bucket of cold water. The black walls were bleeding black; baleful horns and raw, ghostly feedback poured out of the TV screen. I moved, and the tableau ruptured, some of the black lines holding on before the camera wrenched them away. The bleeding—all black, all digital—intensified. Moving through the game-world was like watching the enormous flatscreen in front of me slowly die; mounted to the wall, it had the feel of a crucifixion.

Does this seem intense? It is. XRA is a slight, quiet dude, and you get the feeling that he doesn’t particularly love doing interviews. But his game speaks loudly enough. Its mechanics, such as they are, are diffuse: there is certainly some walking, and some environmental puzzle-solving; in various versions of the game you could jump, or scan; eventually a larger narrative, he told me, will take shape, of an archaic, mysterious piece of software. But mostly what you do in Memories of a Broken Dimension is get your ass kicked by it. “Music game” is a fraught term, conjuring images of plastic instruments and dance mats, but it’s hard to deny the power of sound here, so weighty as to feel almost physically exerted. “I guess in a way this is the outcome of listening to industrial, noise, (and) ambient music and trying to put it into game form,” he told me. (On the GDC show floor, some people were playing the game without headphones, which would be like watching A Hard Day’s Night on mute.)

He cites the Swedish dark ambient project Kammarheit as a particular influence; it’s monolithic, celestial stuff, with titles like “A Room Between The Rooms” that jibe eerily with the game’s shattered, impossible spaces. In the way of a lot of single-person projects, the game’s influences are diverse but cohesive: XRA brings up the confident dark swaths of sumi-e painting, the organic horror art of Beksinski, the angular spaces of Doom and other early 3D games, and the colossal, ruined structures of Tsutomo Nihei anime. Despite the particularity of these reference points, XRA sees his game as part of a small movement.

“There’s this small group of people that are really into the idea of mega structures and just like big infinite spaces,” he said. “People want to experience that in games, because they can’t [in real life], unless they do some crazy urban exploration into a dam that’s abandoned.” Last year’s unlikely triumph NaissanceE, by the studio Limasse Five, is perhaps at the forefront of the movement, but other releases—such as Void One, singmetosleep, and the pitch-black worlds of Orihaus and Aliceffekt—scratch at the same sensation.

And yet Memories of a Broken Dimension can’t help but feel singular. It is wholly the work of one person, after all. The game began as a way to blow off steam after-hours while XRA was doing level design on games you’ve heard of: Gotham City Impostors, Brothers in Arms, Fear 2. Initially his goal was just to play around with shaders and create something more aesthetically in line with his tastes, but it quietly began to serve another function.

“Honestly I think some of this was a frustration from working in the game industry, with some of the stuff that just like, you don’t agree with how something is on the project, but it’s such a big team that you try to put in your feedback and it’s just how it is. I was really frustrated with level design and people being stuck looking at the objective marker the whole time,” he said. “You could do a lot of work to make the level design make sense, but just because of some playtests, or focus tests … There’s a certain percentage of people that are lost and it’s already too late to revise the level design so you just do objective marker stuff.” These conservative ideas would become entrenched, he said—codifying ways of thinking and expectations that stifled creativity on future projects. It makes sense, then, that he would look back as much as inward: As meticulous as much of the level design is on something like Doom, it’s still weird, by today’s standards, still raw and gnarled where we expect order.

Memories of a Broken Dimension is a dagger right in the gut of that sort of streamlining. Out on the GDC floor—audio potentially not on, player potentially shoveling popcorn in his mouth while playing, who knows—XRA saw people deferring to their learned modes. “They first try to go through one of those grid walls and it wraps around and they think, ‘Oh, I’m not supposed to do that,’ and they stop trying to look for openings, and so I’ve been having to remind people that there’s really no wrong way to play this,” he said. “Try to actually break the game. If you think you’re in a weird spot, try to break it, because that’s what you’re supposed to do.” I found myself edging across an isthmus of white noise, but shuddering back to its start, over and over again. I’d push the spacebar, trying to jump, and the screen would flash, becoming a field of ghostly dots. Eventually I just walked off the platform, narrowly landing on some sort of pipe—the right way, as it turned out. I asked XRA if he’s made a game that’s unplaytestable, and he demurred; he wants the game to be playable, and not just for the people drawn in by the power-ambient soundscapes, but as a game, on its own terms.

But before I go, he stops me. “Actually the one thing worth mentioning,” he said, “is, somebody was playing and they saw an eye in the visuals, and they said out loud, ‘Oh I see an eye.’ I had seen the same thing, just as they saw it but without saying it. I thought that was really cool.” I had never thought of playtesting as a means to share a psychedelic experience, but XRA, deep in the gnarled voids of his own making, has his own way of thinking, at this point. “That was a good thing that came out of watching people play,” he said.

Thanks to XRA for sharing some screenshots with us of the game in its most current build. You can check them all out below.