Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain is an unending battle

Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain’s creative director Hideo Kojima must have heard the phrase “war is hell” early in his career and been unable to stop thinking about it since. Past games in the developer’s long-running series have featured straightforward demons, like a seemingly immortal vampire man, a hissing, gas-masked psychic, and a grief-consumed ghost. Each of these characters exists in settings that are otherwise meant to resemble the real world—enemy soldiers sweep and clear areas using tactics informed by military consultants, and the cast’s back stories are shaped by historic events like the Invasion of Kuwait, Cuban Missile Crisis, or Second World War. The previous Metal Gear Solid games have always tempered their plausibility with surreal representations of war. In their superheroic protagonists and moustache-twirling villains, these titles have purposely offset the horror of their subject matter with the abstraction of an irreverent action movie. For decades, the series managed a charming wobble across a perilous narrative tight rope, respecting the reality of global warfare and the pain it inflicts on its victims while still refusing to discuss these issues with an entirely grim face.

It wants to be a serious game about serious issues

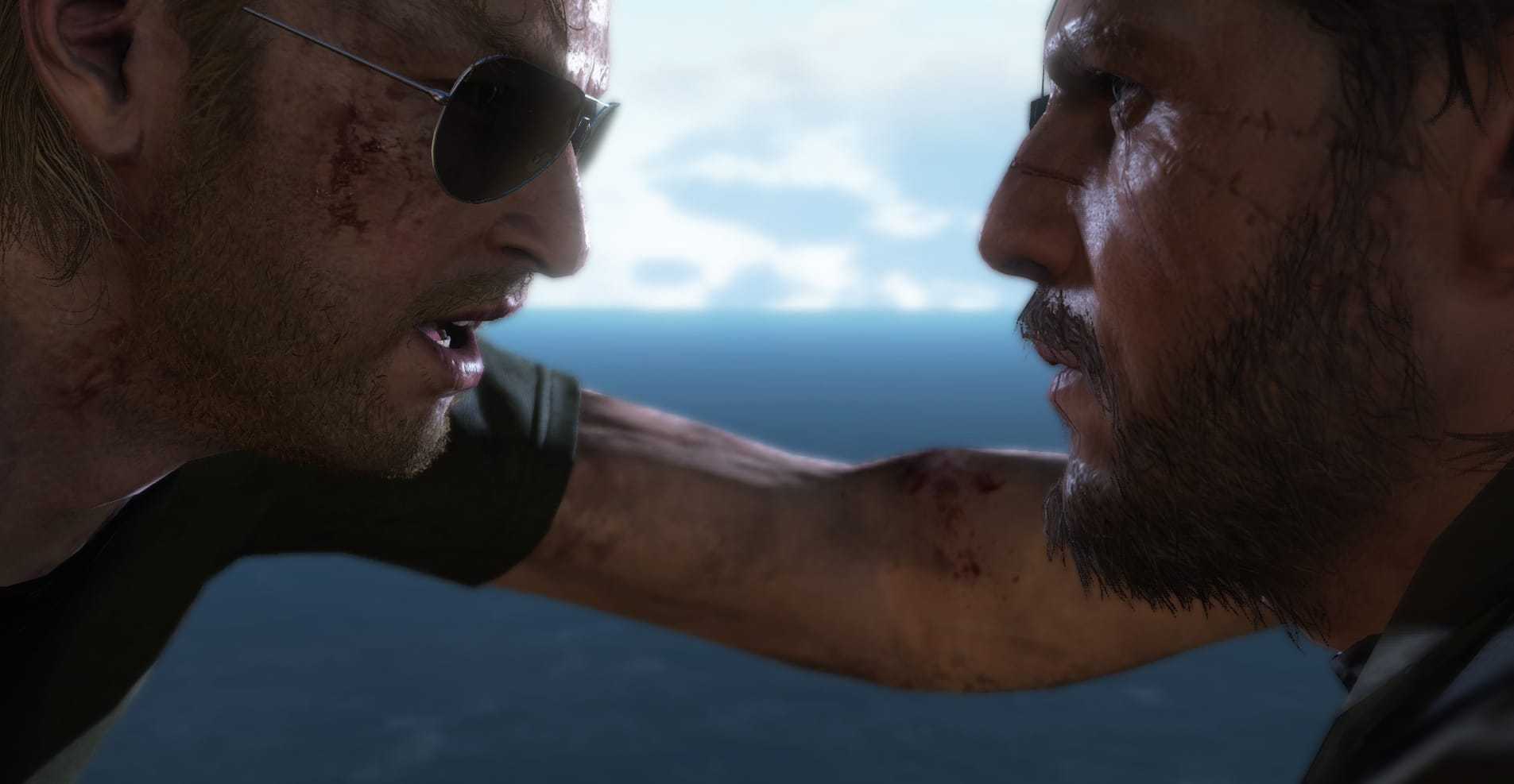

The Phantom Pain’s hell is populated by more ordinary types of demons than any previous Metal Gear. Its story includes human traffickers, scientists conducting ghastly biological weapon experiments on children, and torturers waterboarding captives. There are kids wielding assault rifles in Central Africa and Soviet conscripts patrolling the ruins of Afghani villages. Though all of this is coupled with a handful of cartoonish antagonists—a horrifically burned villain who wears a Zorro mask; a hulking, spandexed figure able to control flame—these figures exist on the periphery of what is largely a story about mundane, distinctly human evils. Unlike past Metal Gear games, The Phantom Pain tries to take some emphasis away from its own tendency toward the fantastic and ridiculous. It wants to be a serious game about serious issues, less afraid to explicitly depict the worst of humanity by forcing its audience’s eyes toward the physical and psychological violence inflicted during the Cold War’s proxy battles.

The player controls Punished “Venom” Snake as he and his mercenary outfit, the Diamond Dogs (no kidding), build up their forces in order to take revenge on the shadowy government branch that almost destroyed them in 2014’s prologue game, Ground Zeroes. To accomplish this, Snake accepts contracts from just about anyone who needs assassinations, infrastructure demolition, or prisoner extraction carried out in his group’s area of operations. The setting alternates between Afghanistan and the Angola-Zaire border region during the last years of the Cold War. As Snake attempts to enrich himself by raising an apolitical army strong enough to defeat his opponents, he earns money and recruits soldiers from battlefields ravaged by the fallout of Western and Eastern proxy wars. The bloody cost of this project—the physical and cultural dehumanization of imperialist violence—serves as one of the game’s constant preoccupations. (In true Metal Gear fashion, the effects of post-colonial linguistic hegemony are turned into a literal threat through a plot device too bizarre to succinctly describe.)

The Phantom Pain communicates its aims more subtly

This is a strong premise, indirectly describing a character’s gradual descent into villainy by making the player complicit in the worst sort of opportunism. And, though the plot moves along with the help of a handful of strong characters like displaced Navajo scientist Code Talker, The Phantom Pain often forgoes lengthy cinematic sequences as a means of telling its story. Instead, it communicates its aims more subtly, presenting the broader goals of gaining money and manpower through seemingly never-ending, repetitive mission objectives. Though controlling Snake as he crawls past search lights, chokes out security guards, and shoots down enemies is enjoyable, exploring the same environments and carrying out variations of the same basic task becomes mind-numbing over time. At first, there appears to be an intention to this, the game telling the player that, though Snake is a perfect soldier capable of astounding physical feats, the battles he fights are ultimately monotonous in their aims and rendered meaningless through repetition.

This fits well with The Phantom Pain’s overarching concern with the grim economics of military adventurism. That this structural repetition slows the game to a crawl at times seems worthwhile in this sense. Snake becomes bloodier and bloodier as he fights; the player gets wearier as they guide him. But the Diamond Dogs gain visible power throughout this, their base expanding and Snake’s access to technology growing with each overly familiar mission. And the promise of new plot points is dangled in front of the player, urging her ever onward.

///

The second half of The Phantom Pain—clearly delineated as Chapter Two—wastes this potential. As Snake descends further into the horror of his personal war, the story recedes into the background, leaving only the numbing grind of the battlefield. Whereas the previous hours provided narrative context with unique mission objectives, this effect is diminished as the game asks players to repeat earlier levels on harder difficulty levels in order to “unlock” plot points that conclude character arcs and allow access to the game’s actual ending.

wants to remind the player that war is, indeed hell

As minor as it may sound, this rocks the fiction off its bearings. A last-minute (clumsily handled) twist ending offers some small justification for the decision, but it’s far too little to compensate for the jarring déjà vu of backward time travelling. When the plot’s pace slackens, it becomes easier to notice the systems at work beneath it—for the magic of enemy artificial intelligence to turn robotic and for the wonderfully detailed jokes (strapping sheep to vertically ascending parachutes, wearing a rubber chicken hat to avoid enemy detection) to become rote.

More than any of this, though, the narrative’s prolonged disappearances take all context away from visual reminders of its exploitative tendencies. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the character of Quiet, a mute sniper dressed only in a bikini top, leather thong, and ripped fishnets. Divorced of story beats that bring some depth to her characterization, the player is left to meditate on how the camera leers at her until she’s effectively stripped of humanity. (One of her first scenes involves two men observing her in a prison cell as she showers; scenes describing her traumatic past or, worst of all, sexual assault zoom in on her breasts and legs, only moving to the emotion portrayed by her exactingly rendered, motion-captured face as an afterthought). As one of Snake’s deployable “Buddies,” Quiet is accompanied by two domesticated animals and a robotic suit, effectively positioning her as a helpful object with no more free will than a machine or well-trained pet.

With only the occasional audio tape to distract from these issues, it becomes difficult to accept them as just an unfortunate part of a greater whole. Quiet jiggles onto yet another helicopter extraction from yet another repeated mission; patting Snake’s dog on the head stops being a nicely extraneous detail and turns into an automatically performed loyalty boosting trick; finishing a non-essential mission transforms from an excuse to spend more time in the game’s world to a method for opening new story scenes. All of this comes together to grind down The Phantom Pain’s charm.

At its best, this is a game that pre-empts the portrayal of a black ops massacre with a zoomed-in shot of the ass crack peeking out of the back of a man’s hospital greens while still, somehow, maintaining a coherent tone. It’s also a game capable of delving into subjects like child soldiers and the erasure of marginalized cultures with legitimate dramatic power. This balance between the absurd and the somber has always been Metal Gear’s strength. The Phantom Pain is different. It, like its predecessors, wants to remind the player that war is, indeed, hell. But, in giving over to structural bloat it obscures the tremendous promise established in its opening hours, trading the narrative power of violent anguish for a routine, Sisyphean take on torment.