Is MirrorMoon EP the first Buddhist videogame?

As gamers, we can be oversaturated with “objective.” Whether that objective is clear to the player, or hidden among layers of uncertain flora, fireworks, devilry, fancy, and/or wandering is up in the air. One might be rescuing fair persons from traps, crafting master swords, or narrowly avoiding banana peels. But one will be headed somewhere.

In MirrorMoon EP, such clarity is shattered with a twelve-gauge shotgun, and the player is left with a million tiny pieces that may or may not comprise a greater image. This, it turns out, is a good thing.

Those eureka! moments define the game.

The game begins in a lonely cockpit. After a misleadingly linear tutorial that outlines the various switching, pointing, and hoisting you’ll be doing throughout the game, you’re presented with an ominous map of scattered planets. These dots quietly vex your will like sirens luring a helmsman toward the rocks.

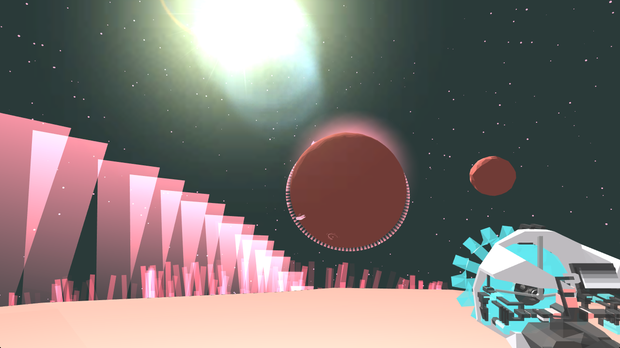

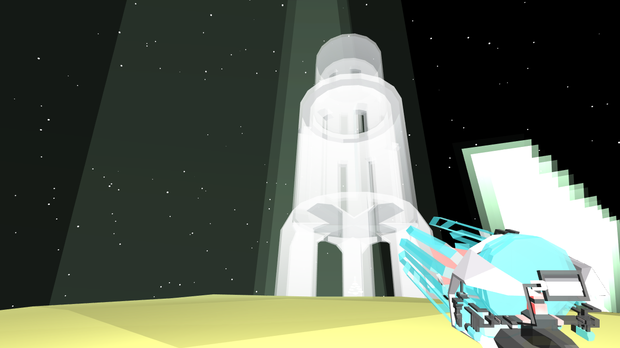

The music is all vaguely electronic burbles, distant space geometry, occasional jarred radio transmission. The world painted on-screen is gorgeous, both on the surrealist planets and your minimalized star hub: swaths of careful color in bright, confident shapes. On the various worlds, the sky ranges from lurid pastel colors to bleak spacious endlessness, like a Windows 95 screensaver come to dazzling life. Every now and then, you’ll come across a swirling hailstorm of light or some other optical trick in which lay a clue to “completing” the planet.

It’s clear the developers want you to figure everything out for yourself, from navigating your cockpit to understanding the point of your existence. Those eureka! moments define the game. You’re blindfolded, spun around three times, and pushed forward.

Perhaps because of this lack of handholding, the sense of loneliness is absolute. As you trudge through, grazing across the surface, you solve “go here” and “touch that” puzzles of various difficulties, rarely as fine-tuned and satisfying as the opening sequence. The lack of digestible goals, challenges, and mission markers seems designed to thwart traditional players.

It’s jarring, then, that the game invests such focus—and such clarity—on the ability to name planets when online. Servers are divided into separate “seasons” of charted skies, and, at the time of this writing, players have already charted up to eight seasons (two up from when I began the game a week ago). That’s eight separate expansive, delirious, seemingly infinite universes. The lure is in being the first to land on a planet—that’s how you get to name it—and there’s something immensely satisfying about exploring a virtual space and knowing that you’re its premiere citizen.

MirrorMoon EP could be an all-encompassing metaphor for the way we fanatically search for purpose in the world

While watching my reticule move from one star to the next, or waiting patiently for my ship to arrive at its next destination—always a brief, sentient repose—peeking at the names of surrounding planets, looking for clues, enough existed in my imagination to want to believe in something out there. And so, I continued searching—for what? I still don’t know.

MirrorMoon EP could be an all-encompassing metaphor for the way we fanatically search for purpose in the world, be it through religion, government, family, or any other belief system. It could also just be a pretty game. Eventually, I was met with the question, “Isn’t this enough? Why does it have to mean anything?” Eureka.

Players are coming together on message boards to ask, “Why am I here?”

This is the type of game I’d give to anyone from the age of five to eighty, almost just to see how they’d play. It teaches non-confrontation and meditation in the guise of space-hopping polygon parades. I wouldn’t be surprised if it was a gift from extraterrestrials to help us with some sort of perspective evolution.

Already, players are coming together on message boards to trade their secrets and rare finds and ask, “Why am I here?” Which, as it turns out, was the objective all along: the discovery not of answers and objectives to complete but of questions and journeys to undertake. This game begs to be played if only to uncover its mysteries.

In this regard, the game is almost Buddhist, asking the player to let go of the desire for objective, goals, and material gain. It presents a vision of space that is at once bleak, endless, vibrant, and resoundingly confusing, a beautiful place in which to get lost.