Who you are in the games industry greatly determines the Game Developer Conference’s worth for you as an attendee.

If you’re an enterprising young coder, you might be there looking for a job. If you’re Ken Levine, you might be there to be weirdly tan and handsome and not talking about your shuttered studio so you can instead espouse wisdom on something called Narrative Legos. You might just be there for the parties and ignore the panels altogether. You might, shockingly, be there to check out some games.

You make plans, and GDC God laughs.

For me, as a writer (I guess), I tend to approach conferences with a Zen-like state of futile acceptance: There’s too much shit going on at these week-long things to act like any sort of plan really makes sense once you hit the ground. There’s always more games being shown than you heard about in the week or month leading up to the show. There’s always some panel you hadn’t heard about before that the blogosphere hadn’t brought to your attention. There’s always more. You make plans, and GDC God laughs.

All of that is to say that the odds are sort of stacked against you if you’re at GDC to show off a game. If you’re press, great, because you can get in for free. But this is the Game Developer’s Conference, which means it’s intended for game developers, not games “journalists.” If you want expo-floor space at “the most prestigious event in the world for professional game developers” (which is quite a horse race, I’ll tell you), a 10’ by 10’ space will run you $7,000. That’s a studio apartment in Brooklyn. If you want a 50’ by 60’ space (a modest living room), that’ll be $210,000, thank you. Some discounts are available but, you know, time is money, as dimestore philosophers say. If you are sinking a ton of time into wading through paperwork and applications, that is crucial time you should be spending on making your game because at the end of the day, that’s what matters, right?

I don’t know. Those are open-ended questions. All I know is I managed to accidentally run into an indie developer from my home state in San Francisco two times at GDC, both times nowhere near the convention floor. The first time was at DNA Pizza, when a friend headed to the DNA Lounge next door, that I ran into the lead artist behind the game that, eventually, I swear I’ll tell you about.

I just think it’s curious and ironic that to be noticed and indie—a word borrowed from the music world, which used to be not a marketing term but a punk-rock “let’s just make shit” attitude—you have to be, as Guy Fieri might say, “so money.” At least in actual-let’s-make-games-for-a-living financial terms. If you truly put your time and mind to making games, it can be as expensive as you allow it to be. (And apparently on a tiered system according to the games industry itself.) So what are your options as an indie? You can slop your game together in a torrented copy of GameMaker under an assumed user name or use the archaic Klik & Play to make things harder for yourself, tangling with a dying design language.

Hugh Monahan and his three comrades at Stellar Jockeys, a Champaign, Ill. independent videogame developer, have opted for the latter. Not to use Klik & Play (look it up, kids), but to make things harder for themselves. They made things harder for themselves by making their burgeoning studio their job. Hugh is one quarter of the company, and he came to GDC in their stead. Later this year, they all hope to move to Seattle, where Hugh’s brother Jack—the company’s lead artist—lives. In the months leading up to that, the guys are on pace to release Brigador, Stellar Jockeys’ first commercial game.

They are not the first guys in the games industry to sacrifice for their craft. I say “craft” not to impart a sense of snootiness, but to communicate the discipline Hugh (and I assume his colleagues) apply to games. Specifically, indie games. Hugh, Stellar Jockeys, and Brigador are indie in the strictest sense of the word.

They were not on the show floor. They did not have a booth, or even a table in the Moscone Center West Hall space relegated for indies to display their wares. Stellar Jockeys had no merch. No swag. No funky T-shirts with their company logo on it trying to act bigger than they were. All Hugh had was his laptop, a great laugh, and a refreshingly unpretentious attitude. He didn’t seem indie at all, and that’s because he actually was indie.

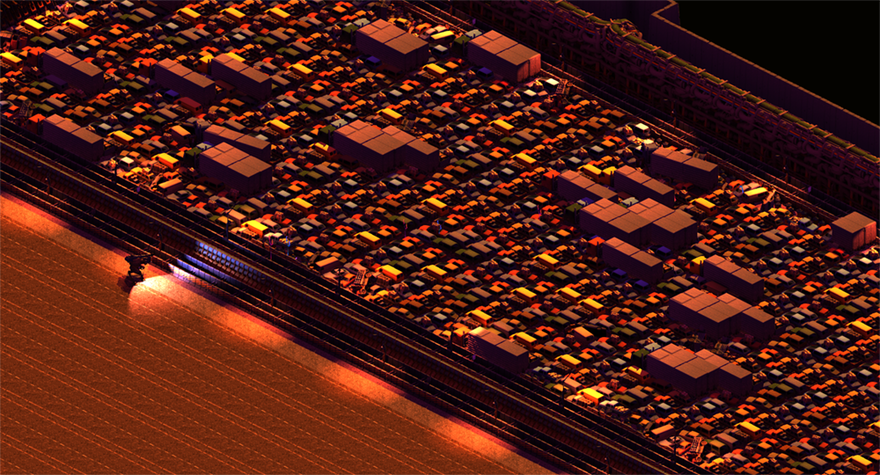

On the surface, Brigador sound like nothing special. It has a funky, vaguely fantasy-sounding name. (It means “fighter” in Portuguese.) But it’s the sort of game you have to see to understand and appreciate.

We met up at a mostly unoccupied table just around the corner from those paid-for third-floor tables. Hugh pulled his laptop out of his backpack and spent an hour with me walking me through his game.

By the end of his demo, everyone else sitting around had risen from their seats and watched over Hugh’s shoulder. There’s something special here, and it isn’t just me who sees it. This is a statement of fact.

Brigador is, quite simply, an isometric mech combat game. Right? Doesn’t sound like anything special. That’s because its specialness lays in its simplicity, although there’s a deceptive amount of stuff going on under its hood.

The game knows what it wants to be and isn’t anything more than that.

In Brigador, you are tasked with choosing one of 20 vehicles (be it a hovercraft, mech, tank, etc.) and embarking through nine city districts, liberating them. This being a videogame, you naturally liberate them by blowing shit up. That’s how revolutions are fought and that’s how wars are won, so why question it.

Hugh says Brigador draws equal inspiration from FTL and The Binding of Isaac, but to my old-man eyes, what I was reminded of was Command and Conquer (if you only control a single unit) meeting Bionic Commando (the NES one with the overworld map, not the new fussy one). But unlike those rigid older games, Brigador strives to give you much more breathing room strategy-wise. In all nine levels, there are three ways to earn the right to move on:

- You can destroy the garrison of troops

- You can destroy all the ammo depots

- Or you can destroy large defensive batteries

Honestly, I wasn’t able to try the game, since Hugh gave me a guided demo, but he was able to flip from level to level at my request and see the implementation of the stuff he was saying. It wasn’t smoke and mirrors. It was smoke and mechs, and it looked intriguingly fun. It looked fun because it was simple. It was clear. The game knows what it wants to be and isn’t anything more than that.

There is no multiplayer. There are no bells and whistles beyond the game’s own super intelligence. To me, this is Brigador’s main draw: It’s as barebones as Marble Madness, but with more emphasis on stealth and physics. You see, unlike Command and Conquer or those older ‘90s games Brigador obviously owes a great debt to, Brigador is isometric in a world that’s three-dimensional and gives its objects weight. The vehicle you use on your run through the nine districts (you can’t switch halfway through, your ride is your ride) determines how you will go about those aforementioned three win-state objectives.

Hugh says “the biggest frustration [we] had with the targeting [in action-shooters] is it used to be you clicked and you hit.” There’s no sense of perspective. There’s no sense that you did anything other than pass a motor-skills quiz when in reality, you should be feeling like you’re driving a fucking tank through a wasteland and you’re nuking suckers foolish enough to get in your way. Great effort was put into creating an active game where the main determinant of your success isn’t your twitch reflexes. Hugh says they wanted to make a game where “your tactical decision-making and ability to react and respond to different situations” will decide whether you live or die.

And you will likely die a lot in Brigador. From what I saw and what Hugh told me, health power-ups are far and few between. This sounds like a bullshit marketing bulletpoint, but Brigador will adapt to your play style. Although there are only nine levels, their layouts and your enemies’ spawn points will dynamically change based on how you’ve been approaching each level. Doing an all-ammo approach? The game will know how to challenge you. Trying to change it up? So will Brigador. Hugh says there’s a special “psycho run” set of challenges that can pop up if you are trying to really keep the game on its toes. A game developer wouldn’t be a game developer if they didn’t make a few lofty promises, and while this does sound queasily like a Peter Molnyeux-esque dream, Hugh had charts demonstrating mathematically how it works. I’m just a writer so don’t understand how it works, but it looks like their hearts are in the right place and can plausibly pull this off. That said, I also didn’t see much of the promised stealth dynamic, but I was bugging Hugh to jump from level to level to show me more, and stealth is hardly an exciting thing to demonstrate. So who knows.

But hopefully they’ll make good on a game you can’t outsmart.

That’s fucking fascinating—a game that, very simply, wants to challenge you. It doesn’t want to dispense achievements to you for spending lots of time in the world, it wants you to win your progress like you had to back in Tempest (look it up, kids).

I know a good game when I see one.

If you want complexity, you can add it yourself. When Brigador hits Steam late this summer for $20 (preorders will be $15), Hugh says Stellar Jockeys plans to support its community by releasing all their assets (there’s that punk-rock indie thing again) and challenging people to make their own levels. He’ll personally be recording videos explaining how they designed some of their levels so you can ape their style a bit—and also because, as he says, “The workflow for some of these apps is a bit non-intuitive.”

I think that’s why Brigador fascinates me so much. Stellar Jockeys has been so unflinchingly uncompromising in its pursuit of this game that it’s hard not to root for it: it’s taken them two years to develop, they scrapped several previous versions they got very very far on, they built their engine entirely from scratch (something that stands in direct opposition to Gone Home’s Johnnemann Nordhagen pro-laziness GDC talk earlier that week), and it has a very crisp sense of what it is. It’s why I think everyone else at the table took notice and got out of their seats. It’s why I’m writing this right now. It’s why I describe Hugh and Stellar Jockeys as approaching games as a craft, not some hipster chess game to get noticed on a blog. Those are both worthy pursuits, but all Hugh and Stellar Jockey want is to make fucking games.

And I’m right there with them. I don’t know what the fuck narrative legos are, but I know a good game when I see one. Hopefully when I finally play it, Hugh doesn’t make me look like a liar. But I’d stake my “privileged” press pass on it.