This article was written by Stephen Beirne and originally published on Normally Rascal.

It was brought to us by our friends at Critical Distance, who find the best in critical writing about games each week. You can see more at their site, and support them on Patreon.

///

In a recent video on Persona 3, I talked about how the dating sim-slash-dungeon crawler uses its menus to overlay a certain optimism towards the glacial crisis that was—and still is—complicating the future of Japanese society. This aspect of Persona 3’s menus arises from an assumption I make, and I don’t think it’s too controversial an assumption, about menus existing in games as a mode of introspection.

What do I mean by this?

In an alternate universe I provided a couple of examples to give this interpretation more weight, one example of which was the codec menu in the Metal Gear Solid games. Unlike that marvelous alternate universe, however, time in our universe runs at a rate of one second per second, and to keep the video short and within its scope the example of Metal Gear Solid had to be cut. Instead, I’d like to expand the idea in this article, partly as a complimentary piece to the Persona 3 video, and partly to justify a shabby and safe assumption about videogames that as far as I can tell nobody has contested.

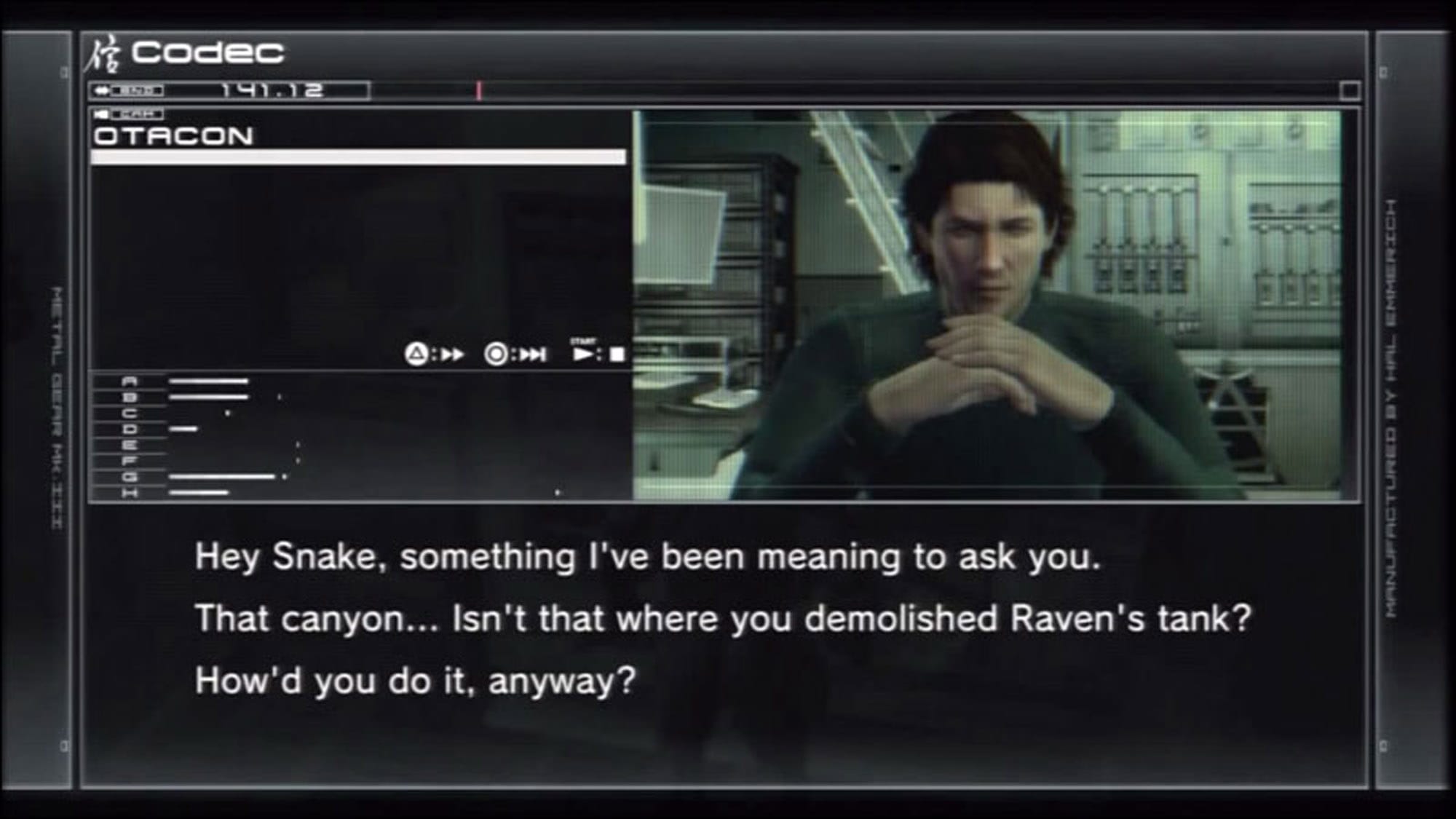

There is one important thing to note about Metal Gear Solid, in case you haven’t played it, that if we were to get out our scalpel and divvy it up into bits the same way that comes naturally to Persona 3, we might say its structure falls into three categories convenient to a menu analysis: action/stealth areas, cut-scenes, and codec calls. I put ‘cutscenes’ in its own category because, as the franchise went on, this became a bigger and bigger facet of each installment, both textually and in the eyes of either elated or frothing players.

maybe the ‘real’ world itself doesn’t exist—guards freeze in their spots, security cameras halt mid-whir

Codec calls have a special place within this structure as they represent the innermost sanctuary of Snake, our character. A codec call occurs on its own menu screen separate to the ‘action’ of the outer gameworld, which, as we might normally view it, would be the ‘real’ gameworld. It accentuates the values of the ‘real’ gameworld with respect to how Snake moves through and lives in the latter: shyly, diligently and safely. If you play MGS the way it suggests it should be played, you probably move Snake around coyly, gathering up information about the level and your enemies while guarding your position and minimizing your presence. You plan your route. You wait patiently.

Snake is a very patient person, which explains why he’s willing to keep his gun readied while the next boss character postures and flourishes, and only fires when it’s clear their monologue is complete. It also explains why the MGS games have so many long, long cutscenes: because Snake is patient, and if you’re identifying with Snake and you enjoy Snake, you might want to be patient too.

This imbued sense of patience is further instilled through how MGS orchestrates Snake’s movement through a combination of player controls and camerawork in the action/stealth bits. It builds an inverse relationship between Snake’s mobility and his power, that when they are physically inactive the player is most advantaged with the knowledge of how to wend through the level.

In the codec menu Snake is at his most prone, in that he effectively loses all outward-facing mind and bodily defenses. His thoughts are elsewhere; he does not spiritually exist in the ‘real’ world anymore. Or maybe the ‘real’ world itself doesn’t exist—guards freeze in their spots, security cameras halt mid-whir. It does exist, but it’s as if it doesn’t. It’s as if everyone and everything accepts the codec menu has been opened and affect a form of existence accommodating Snake’s most emphasized characteristic. They wait patiently.

And why?

If we want to be sensible we could say it’s just a videogame thing. It could easily be like Dark Souls where the ‘real’ gameworld keeps ticking while we browse our menus, so players always stand the chance of being mobbed while they’re trying on new shoes. That works well within the cosmology of Dark Souls and we accept it. Metal Gear Solid is quite un-Dark Souls cosmologically, however, so if we say everything freezes just so players don’t fume when Snake gets gunned down during another bloody mandatory codec call, that’s fine and grand. But since MGS is a romantic game, let’s ourselves be romantic for a minute in considering what role the codec plays, what functions it fulfills, and what knowledge it imparts.

Codec calls are an information resource, fundamentally, on esoteric context for the story situation in the pretend broader political world. Or as a manual for gadgets and bobs Snake’s got in his trouser pockets. Or, in cases where Snake and company have a natter about Chinese philosophy and, in later games, vampires and Bond movies and Jack Do You Remember Our First Date, for pleasingly indulgent (or ungenerously: over-wrought) character writing.

Knowledge empowers Snake in how we inhabit him, and the patient gathering of knowledge is the utmost expression of his magnificent self, stealth-wise. A lot of the time it’s not useful knowledge from the codec, such as the position of a local air vent, but more abstracted, especially in terms of what the player “should do” next towards the game’s completion. Abstracted knowledge lasts longer, it overhangs the situation of Snake’s mission, and in some ways has greater durability. Nobody remembers being told about the air vent but everyone remembers Mei Ling’s proverbs.

The codec is therefore a reservoir of staying knowledge, albeit at some points in Metal Gear Solid 2, to the displeasure of more than a few impatient players, a seemingly unending one. This is where Snake goes to learn, and since knowledge is power, this is where Snake is invincible. He cannot die when in the codec menu; bullets hang existentially petrified in midair when Colonel Campbell comes a-calling.

Nobody remembers being told about the air vent but everyone remembers Mei Ling’s proverbs.

Not literally, of course, because the menu is not understood as a literal space. It’s a figurative space, an amalgamated personal and metaphysical space central to Snake. It’s his safe space, the safest space he can find as he plunges through the marrow of hostile enemy territory. We understand this innately a lot of the time, we fans of the codec. Sometimes you want a bit of downtime from the stealth and the action, to sit back and chat with your support team about… oh, about military vehicles or memetics or food or how weird that last cutscene was. It’s pleasant. It’s like home.

And this is why many of the dramatic twists within and surrounding the codec work. Miller’s reveal as Liquid is a betrayal because it’s a long, subdued invasion of Snake’s most Snake-like space. The banjaxed AI Colonel disrupts Raiden’s sense of reality because it’s a deep-seated subversion of what we felt was sanctuary. The strangers Deepthroat and Mr. X unsettle us because they don’t belong here, so secretive, withholding, despite appearing vaguely benevolent in the advice they share.

You have probably guessed by now that I rather enjoy the codec menu in the Metal Gear Solid games. I am the sort of person for whom the highlight of any Mass Effect is when I make a sandwich, put on the kettle and sit down to listen to Neil Ross narrate text log after text log. I don’t mind waiting through reams of lore if it’s cleverly positioned.

This is a good fancy to lay claim to from Metal Gear Solids one through three, where codec calls first swelled in length and frequency and then reduced to a bulk more digestible for most normal folk. Since MGS4, though, they’ve been gradually tweezered out from each successive game’s structure. When MGS4 introduced a robot companion to serve as the mechanism through which calls are conducted, its liveliness alongside Snake in the ‘real’ gameworld allowed traditionally codec-natured conversations to enter the realm of cutscenes, reserving the codec menu for shorter and/or optional bursts. Peace Walker followed up by diffusing it between tiny, concisely informative, real-time barks from Snake’s support team, and externally placed audio logs accessible between missions rather than in the field. It facilitated the game’s portable-intended structure, designed more for commutes than long weekends.

When last year’s Ground Zeroes retained this model, it rode on the sea change towards a (mundanely) grittier cosmology, one less interested in introspective metaphysics. For many players the death of the codec is a long-awaited victory. Not for me. For me, it is debris where once was haven.

///

This article was written by Stephen Beirne and originally published on Normally Rascal.

It was brought to us by our friends at Critical Distance, who find the best in critical writing about games each week. You can see more at their site, and support them on Patreon.