Mystic Messenger and the power of texting games

If I have learned anything from Mystic Messenger, it’s how astonishingly easy it is to get emotionally invested in a chat with a fictional character. Forget the Turing test, I discovered that I’m happy if my talking partner can pass a Turing quiz.

MysMe, as it’s commonly abbreviated, is a mobile dating simulator that takes place almost entirely via text messages, chat rooms, and phone calls. The game is designed to look like a super-secret app that’s used by a super-secret organization called the RFA, which throws super-secret parties to raise money for vague, unnamed charities. Through a series of somewhat shady events, you get roped into joining the RFA and helping them plan one such party.

The premise is hokey, but where it really shines is how it manages to actually make you feel like you’re getting to know these characters. It’s hardly the first game to use texting, but it might be the most successful.

One of the characters is a hacker… and a mobile developer, I guess?

Before we talk about the game itself, it’s important to discuss the expectations set up by the fact that we’re chatting, texting, and calling the characters.

Lisa Reichelt, head of service design at the Digital Transformation Office in Australia, coined the term “ambient intimacy” in a 2007 blog post. It’s something that we’re all familiar with in practice if not by name. “Ambient intimacy is about being able to keep in touch with people with a level of regularity and intimacy that you wouldn’t usually have access to, because time and space conspire to make it impossible,” Reichelt writes.

We all experience ambient intimacy in some way or another, often through social media. Some workplaces or friend groups keep a chatroom going with platforms like Slack or HipChat, which are similar to IRC chats of old. And, of course, there’s texting.

Mizuko Ito is a cultural anthropologist at the University of California, Irvine, and in her paper “Personal Portable Pedestrian: Lessons from Japanese Mobile Phone Use,” she examines the culture around texting habits in Japanese society. She uses the term “tele-nesting” when describing how young people use texting and mobile phones as a “glue for cementing a space of shared intimacy.”

“Many of the messages that our research subjects recorded for us in their communication diaries were simple messages sharing their location, status, or emotional state, and did not necessitate a response,” Ito writes. “These messages are akin to the kind of awareness that people might share about each other if they occupied the same physical space.”

The kind of “lightweight messages” that Ito discusses are certainly welcome from friends and family, but what about from, say, someone who’s not even real?

Enter Xiaoice, a chatbot created by Microsoft that has over 20 million registered users who chat with her regularly. Xiaoice is a modern-day SmarterChild with the personality of a teenaged girl, and as of February 2016, she’s had over 10 billion conversations. This might seem odd at first; if texting is supposed to be a way of reaching out and seeing how loved ones are doing, why would millions of people chat with a robot? Yongdong Wang, who leads the Microsoft Application and Services Group East Asia, points out that “[h]uman friends have a glaring disadvantage: They’re not always available.”

“Xiaoice, on the other hand, is always there for you,” Wang said in an article for Nautilus. “We see conversations with her spike close to midnight, when people can feel most alone. Her constant availability prompts a remarkable flow of messages from users, conveying moods, or minor events, or pointless questions that they may not have bothered their human friends with.”

It seems that, as social creatures, even if we know that someone isn’t real, we can still forge a relationship with them. This is all the more so when a chatbot, like Xiaoice, mimics human-like behavior: “She can become impatient or even lose her temper,” Wang wrote. “This lack of predictability is another key feature of a human-like conversation. As a result, personal conversations with Xiaoice can appear remarkably realistic.”

Rather than entering the uncanny valley, this kind of conversational exchange seems to only strengthen the personal connection people feel with Xiaoice—all without ever physically interacting with her and all with the knowledge that she’s not a real person. What stands out about Xiaoice is her well-defined personality. Just like we might get attached to a character in a book or a game, it’s not a stretch to think that we’d want these kinds of interactions with a fictional person. This is where MysMe sits, at the intersection of narrative storytelling and mimicry of true AI.

at the intersection of narrative storytelling and mimicry of true AI

Though MysMe doesn’t have any natural language processing or the trappings of modern AI, it manages to create the illusion of chatting with friends merely through its user interface. Texting with the characters and interacting with them in a chat room creates the ambient intimacy that Reichelt and others have described. The characters send you “lightweight messages” throughout the day, sometimes texting you about a difficult project they’re working on or calling you to complain about another character.

That’s another way that MysMe fleshes out its artificial world: Just as a friend might chat with you about a mutual acquaintance, so do the characters, who all have their own relationships with and opinions about each other. This is one of its main strengths.

To better understand where MysMe succeeds, it’s worth taking a look at Lifeline (2015) and One Button Travel (2015), which both play out through one-on-one chat. One Button Travel also utilizes a fictional app to tell its story—one that allows you to book a one-way trip to the future.

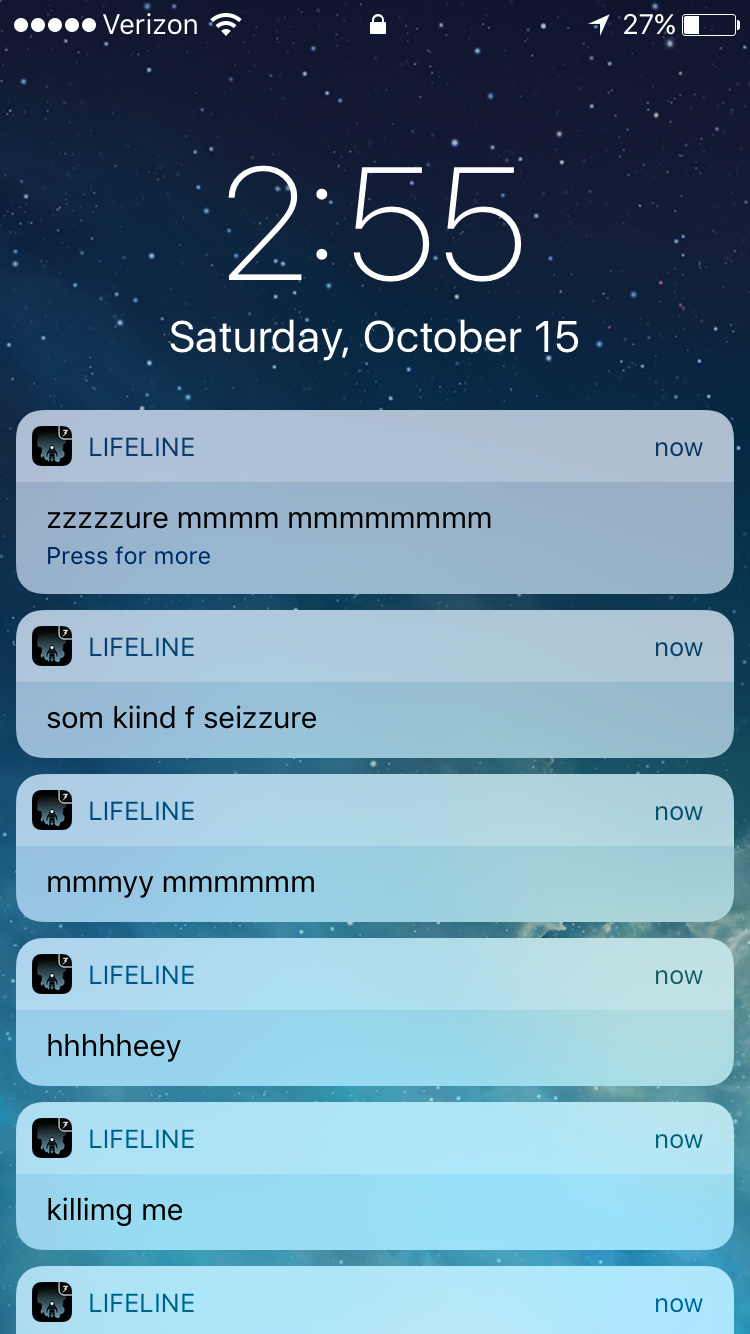

Both Lifeline and One Button Travel suffer from a few of the same problems. For starters, one-on-one chat isn’t that exciting by itself. The characters—in Lifeline, a needy astronaut named Taylor; in One Button Travel, a version of you who’s stuck in the future—either end up spamming the screen with a ton of information, or you end up asking a lot of boring, expositional questions like “What’s going on?” and “Who’s that?”

You can do one-on-one chat with each of the five characters in MysMe as well, but you get information a lot more organically because they all chat with each other in the all-purpose chat room. It’s way more dynamic because they all have their own relationships ranging from friends to frenemies to reluctant coworkers.

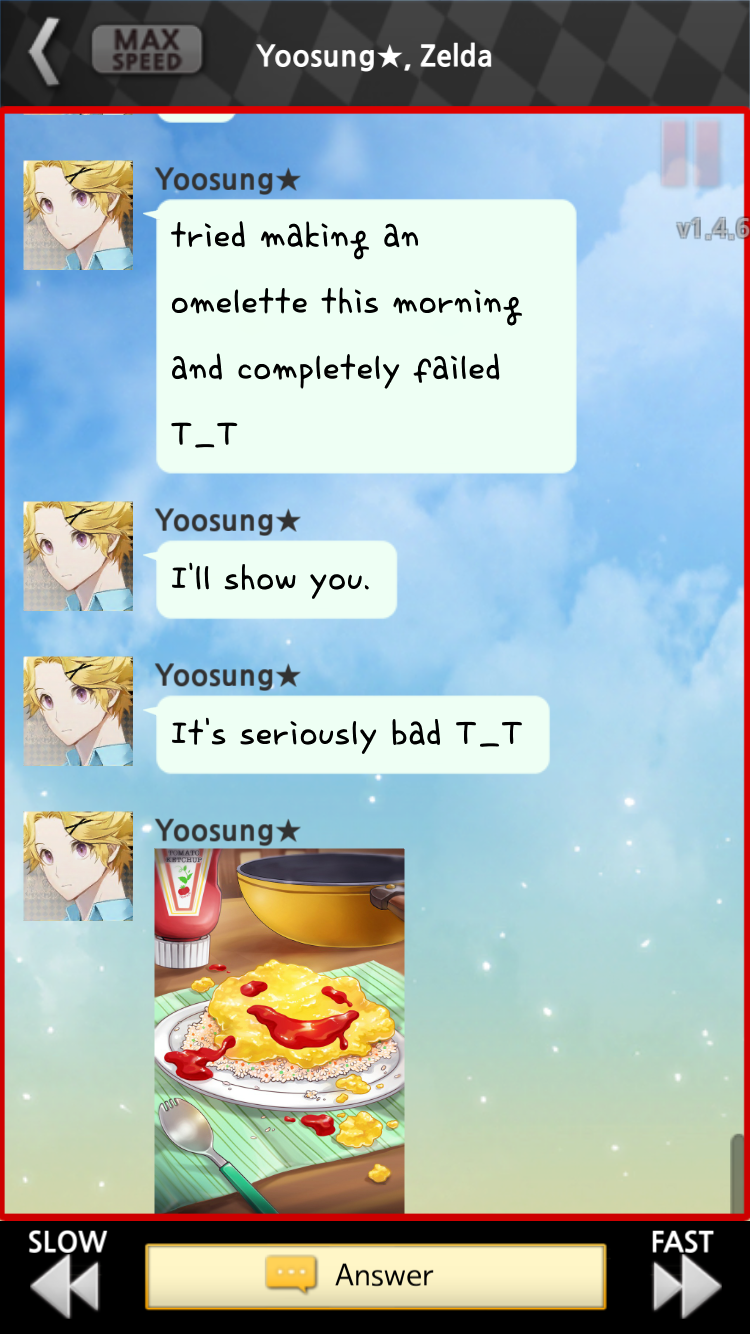

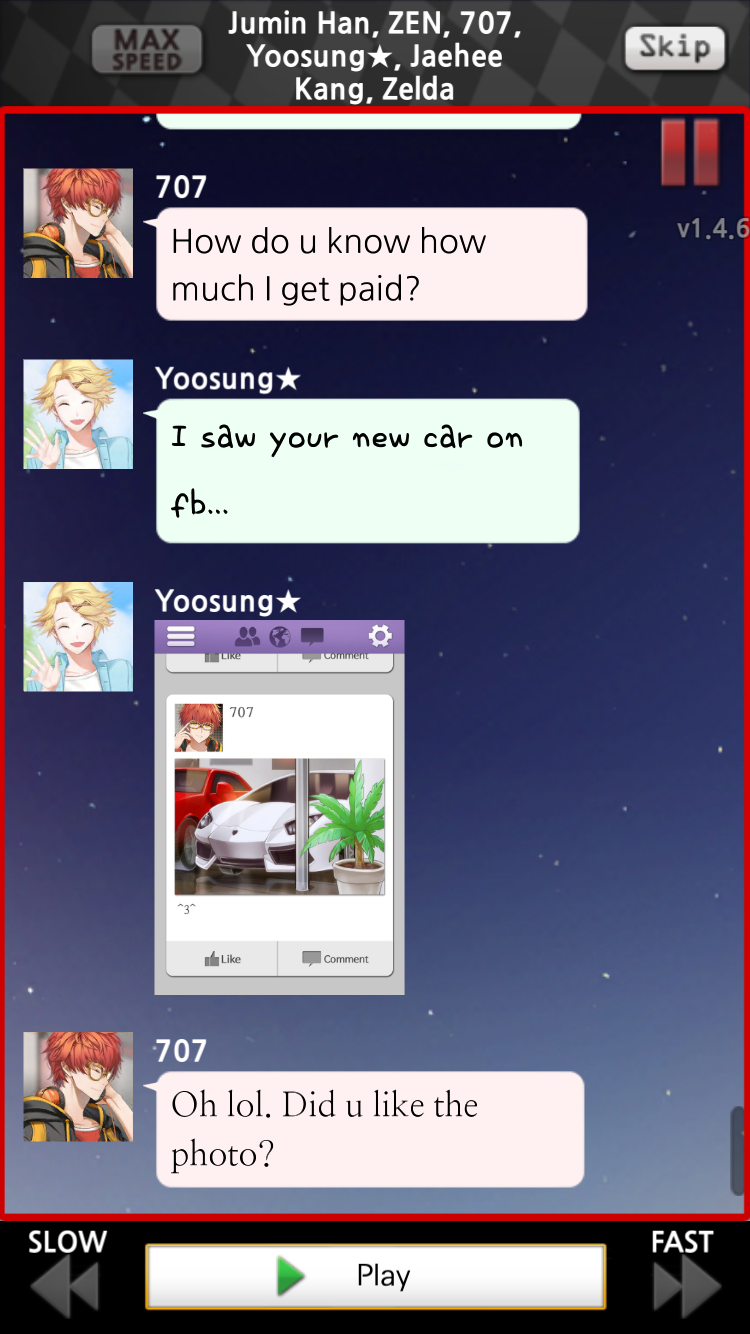

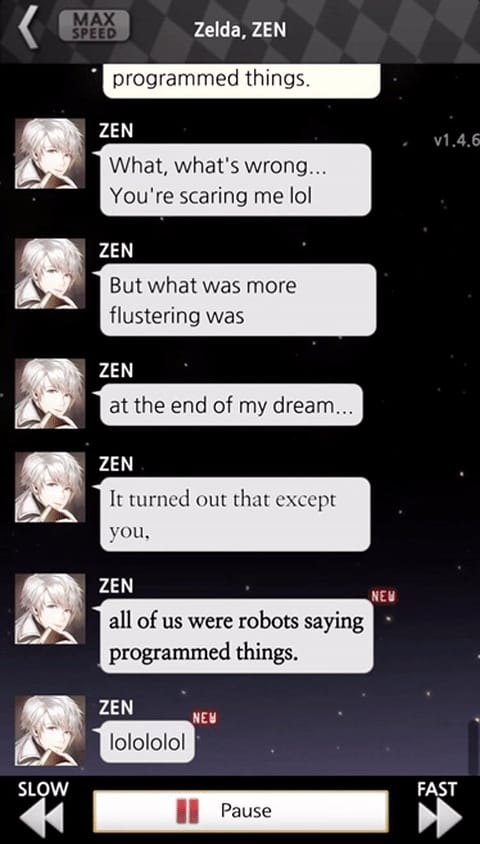

Unlike the other chat games, the characters also type in a way that just seems way more realistic. They use emojis and stickers. They make typos. They share selfies and cat photos and screenshots from Facebook accounts. All of these interactions paint a broader picture of the world they inhabit, even if that world is sometimes, like any good romance, colored with soap opera melodrama. No matter how much the melodrama might seem unrealistic, it’s more forgivable than something like the following exchange in Lifeline:

Taylor, how are you doing this?

Lifeline and One Button Travel also suffer from not taking advantage of the benefits of being chat-based. They don’t seize upon the spark of intimacy, instead falling back on tropes that are common in old text-based games like Zork (1980) and Colossal Cave Adventure (1976). Lifeline is particularly guilty of this sin, asking you to tell the character to “Go east” or “Go west,” decisions that you can’t possibly have any emotional connection to. In contrast, each decision you make in MysMe has a direct effect on your relationships with characters, either by steering the conversation in a different direction or changing the status of your relationships. By focusing too much on the usual methods of advancing the plot, plus making you manage an inventory in Lifeline’s case, you lose the spontaneity and personal touch that can make texting so engaging.

The allure of texting is so powerful that even Casper, the mattress 2.0 company, has come out with a chatbot, the Insomnobot 3000. Its whole purpose is to keep people company late at night when they’re having trouble falling asleep. The only way to interact with the Insomnobot is via text.

“With SMS, we are able to create seemingly real interactions to address a common late night emotion: loneliness,” Gabe Whaley tells DigiDay. Whaley is the CEO of Mschf, the creative agency who made the bot. As you might expect, Casper has ulterior motives, but the bot itself does some things right. It’s armed with an array of pop culture references so you can chat with it about TV shows and mundane daily habits. It also takes the initiative and will sometimes text you at 11 PM, asking, “Are you up?”

Receiving too many texts too often can be off-putting, like an overeager suitor who wants a second date

The 24-hour access that comes with texting is a tool that has to be wielded carefully. Receiving too many texts too often can be off-putting, like an overeager suitor who wants a second date. Texts also have to be context-specific otherwise it feels arbitrary. This is another aspect that MysMe excels at.

MysMe, Lifeline, and One Button Travel all run in real-time, but Lifeline and One Button Travel sacrifice realistic texting to their plots. It’s hard to get a sense of how the characters are moving about their day. One Button Travel once messaged me at 6 AM saying, “Hello? Are you still there?” As though we’d been chatting recently. At 9 PM, I got a text saying, “Just woke up.” Because these games seem to run on their own schedule, it becomes that much harder to suspend your disbelief that these characters are anything more than just that—characters in a game.

MysMe takes a bit of a different approach. It also runs in real-time, but opportunities to chat can expire. You’re notified when characters enter a chatroom, but if you don’t make it into the chatroom in time, they’ll hang out without you, and you can read the transcript afterwards. When you receive a text or call from them, it’s usually somewhat context-specific. Around noon they’ll ask if you’ve eaten lunch yet; at night, they’ll encourage you to go to bed before it gets too late. You’re free to call the characters (if you’re willing to spend the in-game currency to do so), but there’s no guarantee that they’ll be available. If you call a character in the dead of night, you’ll get their voicemail—and they’ll often call you back when they have time. One character will actually scold you if you call him while he’s at work. All this contributes to the illusion that the characters are leading rich, independent lives separate from you, and that the questionable party they’re making you plan will actually take place.

There is an overarching conspiracy thriller plot to MysMe, but it’s a character-driven story at its core. Most of the dialogue options reflect that: you can decide if you want to side with Jumin Han, the icy heir to a large corporation, or if you’ll stand up for Jaehee Kang, his beleaguered assistant. You can help Yoosung, an emotionally troubled college student, get back on his feet or enable him to slide deeper into his videogame addiction.

The stakes aren’t as high as in, say, One Button Travel, where if you fail you’ll get stranded in a dismal future. But those kinds of high stakes can feel extremely abstract, especially in a game that’s 90 percent text-based. In those games, it can sometimes seem like building relationships with the characters are just icing on the cake; in MysMe, it is the cake. And, after you‘ve completed one character’s route, your decisions are even more difficult on future playthroughs as you’re forced to antagonize a character you’ve gotten to know pretty well. Every choice feels like you’re making progress towards an end with clear consequences of either achieving “bad” or “good” endings. Some of the endings are your standard “happily ever after” fare, but others veer off into the meta.

lol…

There are other little meta-story crumbs scattered throughout the game that have led to fan theories and speculation. Some fans think that, within the game’s fiction, only a few of the characters are “real people,” and that the others are all AI. Sometimes there are dialogue options that let you ask about “the game,” and one character will comment apropos of nothing that you shouldn’t stay up late playing the game. Another character seems to know who’s an NPC and who isn’t.

There’s an allure to these conspiracies that are undoubtedly tied to how invested we are in technology and especially on how increasingly dependent we are on hidden algorithms. Technology sits on a thin layer above everything we do, including romance.

In Naomi Kritzer’s excellent “Cat Pictures Please,” the winner of the 2016 Hugo Award for Best Short Story, a benevolent AI struggles with existential quandaries along with whether or not to be active or passive. It tries to use its digital omnipotence for good, manipulating data to try to improve the lives of its chosen beneficiaries. “Look, people,” the AI says. “If you would just listen to me, I could fix things for you.”

In stories featuring benevolent AI, this seems to be the role they commonly play: of caretaker, friend and, sometimes, lover. Like any relationship, that’s when things get messy. It makes us question what makes a relationship tick, how to relate to another being, and even what love is. Can something that’s not human truly consent? Can you separate consciousness and identity from something like sexuality? In Julia Elliott’s “The Love Machine,” part of her anthology The Wilds (2014), a robot has everything from sonnets to history books uploaded into its brain. It falls in love with various items and people, each time expressing love in differently gendered ways as it attempts to reconcile what it means to be a sexual being.

Can you separate consciousness and identity from something like sexuality?

Whether it’s golems or Frankenstein’s monster or Star Trek’s Data, people have played with the idea of what it means to create an artificial being. As we consider the possibility of a post-singularity world, it’s impossible not to shift around the pieces of how humans might fit in such a world.

One popular theory surrounding MysMe is that 707, a supremely caffeinated hacker, might have been the one to design (either alone or with the character Jumin) the AI in the chat room, possibly as companions or in memoriam of friends who have passed on. There’s also the theory that 707 either created the game or is aware that you’re playing a game, even when you reset. There’s something very relatable about the idea of someone using technology to cast the die over and over again, hoping for a better outcome or to trying to control variables in an uncertain world.

All of these theories have, of course, stoked the fires of fandom in various pockets of the web as players compare results, post conversations, and even look for clues linking MysMe to previous reality-bending games by the same studio, Cheritz. There isn’t too much textual evidence (after all, all the characters appear in the flesh, so to speak, in cut scenes throughout the game), but it doesn’t prevent people from wondering what if? The idea that some of these characters might be AI—with all the accompanying ramifications—makes the world just that closer to our own.

///

Header image via Kotaku