Neocolonialism throws up a middle finger, but is it justified?

Ruin everything and get rich. Neocolonialism is quite simply a digital board game about getting the most money, but it might be better described as a scheming simulator—a playground for those who want to flex their guile. Its Kickstarter video and presentation indicate a game along the lines of Settlers of Catan, but to suggest that it shares anything but inspiration would do this game a great disservice.

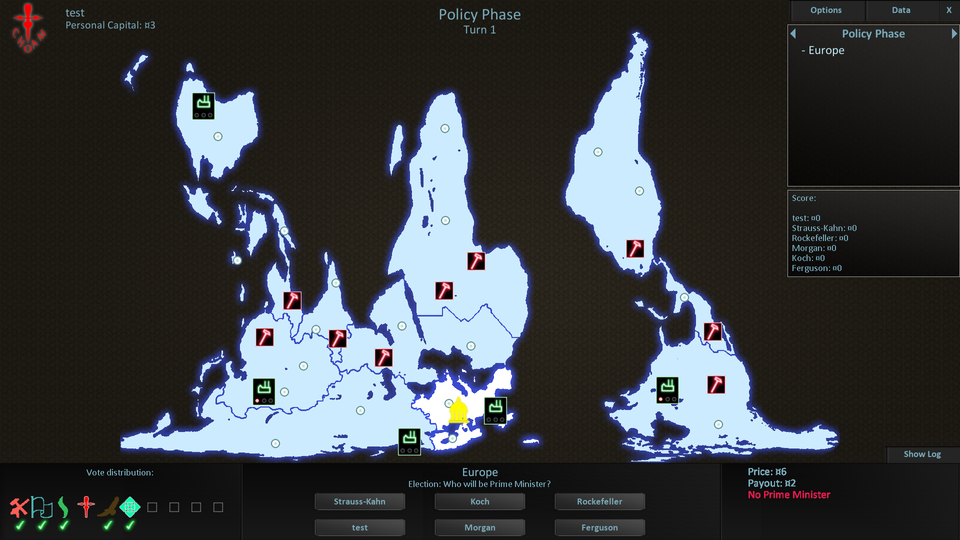

The mechanics in Neocolonialism are easy to learn, but play is infinitely complex because it is all based on the interactions between players. There are mines to be dug, factories to be built and countries to be controlled, but these are just kindling to bring your mischief to a boil. They are not ends in themselves, as this not a game of property. These objects are merely pawns in a game of influence, which can and often are discarded at a moments notice.

What could be better? The longest road? Trading Park Place for four railroads? I assure you not.

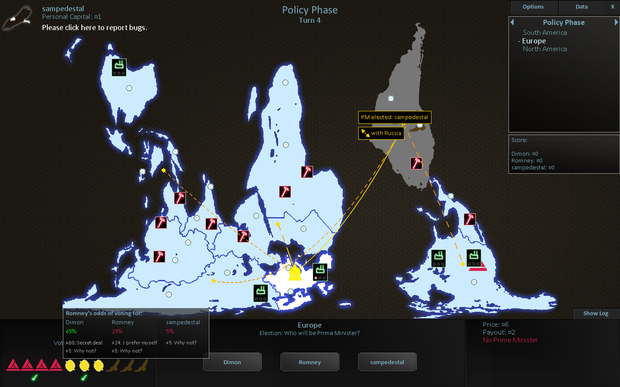

Players are only as successful as the current round. The ploys of others could turn a resolute dictatorship into a lonely and isolated opposition party in parliament. In one moment a player could have all their political influence devoted to a plurality in North America, and in the same turn they can liquidate this political capital, become the dictator of Africa and agree to vote another opponent prime minister in South America if that player agrees to do the opposite for them in Australia. Players are encouraged (often required) to tolerate the success of others to bolster their own. Neocolonialism is filled with as much quid pro quo as backstabbing to glorious and more often horrifying results. And what could be better? The longest road? Trading Park Place for four railroads? I assure you not.

In the last round of Neocolonialism, after all the conspiracy, teamwork and machinations, players dump their investments and the one with the most money wins. The game is over, a helpful message informs you, but it also asserts that the world is ruined. Ostensibly this is the takeaway, the result of neocolonialism itself: that diabolical leaders get rich and the world is left in tatters. All the players were certainly rich, but I found myself less convinced that the world was ruined.

This presentation leaves little room for interpretation: you are a villain.

The narrative of Neocolonialism is one someone might generate after reading Das Kapital and The Jungle back to back. Alter claims that the game is sarcastic. It would be better described as partisan and derisive. The AI players don the names of British PMs, former heads of the IMF and American captains of industry. Every time the game is launched a random quote appears which will most assuredly make you despise those who utter them. A line from J.P. Morgan reads, “I owe the world nothing.” This presentation leaves little room for interpretation: you are a villain.

There is a positive side to capitalism that is revealed by the map.

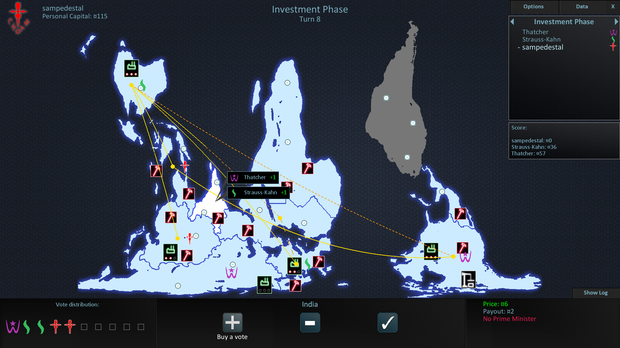

Yet this negative framework is mostly a that, framework, and these trimmings don’t necessarily match up with the resolution of a game. When all the players walk away from the board, recently built factories lie across the world, trade exists between nations and economies have grown. Sure, the players have all skipped town with a nice payout, but the world is a far more developed place. Alter doesn’t highlight any of these aspects, but he can’t hide them either. There is a positive side to capitalism that is revealed by the map.

One of the AI opponents is Andrew Carnegie, a man who in his lifetime gave away hundreds of millions of dollars (adjusted for inflation). He is, of course, controversial and has performed less than noble acts, but you can be sure you will not see any of his decent side. Read his essay The Gospel of Wealth where you will find the quote:

“This, then, is held to be the duty of the man of wealth: To set an example of modest, unostentatious living, shunning display or extravagance; to provide moderately for the legitimate wants of those dependent upon him; and, after doing so, to consider all surplus revenues which come to him simply as trust funds, which he is called upon to administer, and strictly bound as a matter of duty to administer in the manner which, in his judgment, is best calculated to produce the most beneficial results for the community…”

A little too moralizing, but not such a bad outlook. You most certainly will not see this quote in Neocolonialism because this is not the story Alter wants to tell. He wants to paint wealth and its accumulation as inherently negative, and in a lot of ways he succeeds. The player’s choices are calculating and selfish. But this is not a zero-sum game. If you look at a map when all the players have cashed out, there is more to wealth than the loss of others.

Alter’s desire to portray a specific point of view cannot overpower the dynamic inherent in what he has crafted. Certain aspects run away from the story he is trying to tell, but this is ultimately a testament to the strength of Neocolonialism. As problematic as the thesis is, this is an experience where the players end up in control of the game, not the author. Which is fortunate, because it’s the game here that shines.