The FAILE: Savage/Sacred Young Minds exhibit is currently on display at the Brooklyn Museum through October 4, 2015. More information can be found at the Brooklyn Museum website.

///

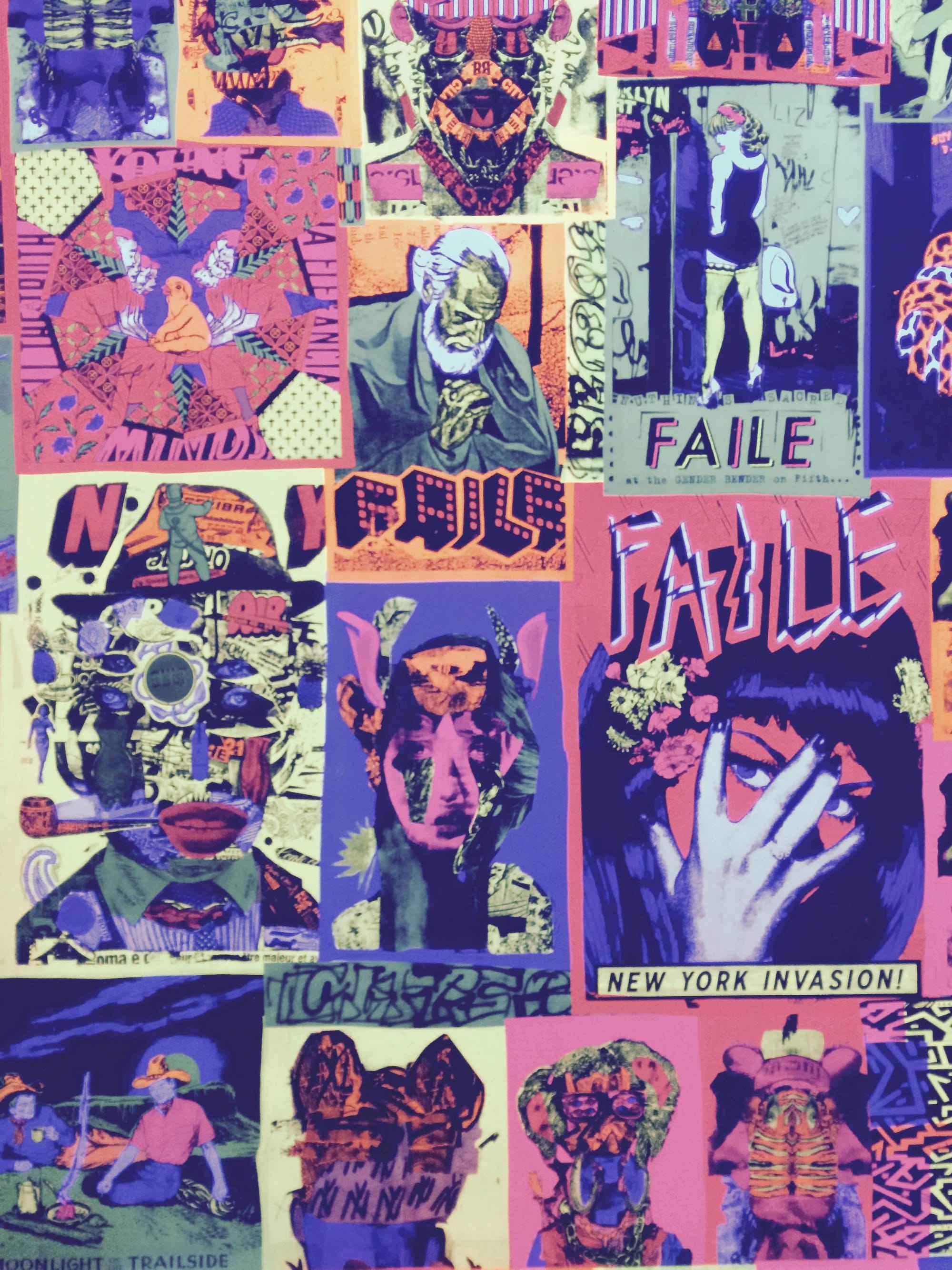

Step out of the elevator onto the fifth floor of the Brooklyn Museum, walk through a set of double doors, and I promise you won’t miss the life-sized ruined structure with iron gates, stone carvings, and stylized tiles. Look a bit closer at what the images depict and you’ll immediately feel a sense of familiarity. The images are an amalgamation of ‘70s corporate media typography, comic strips, skateboard culture, indigenous patterns—and then, all of a sudden, a scuba-diving horse that looks a whole lot like BoJack Horseman.

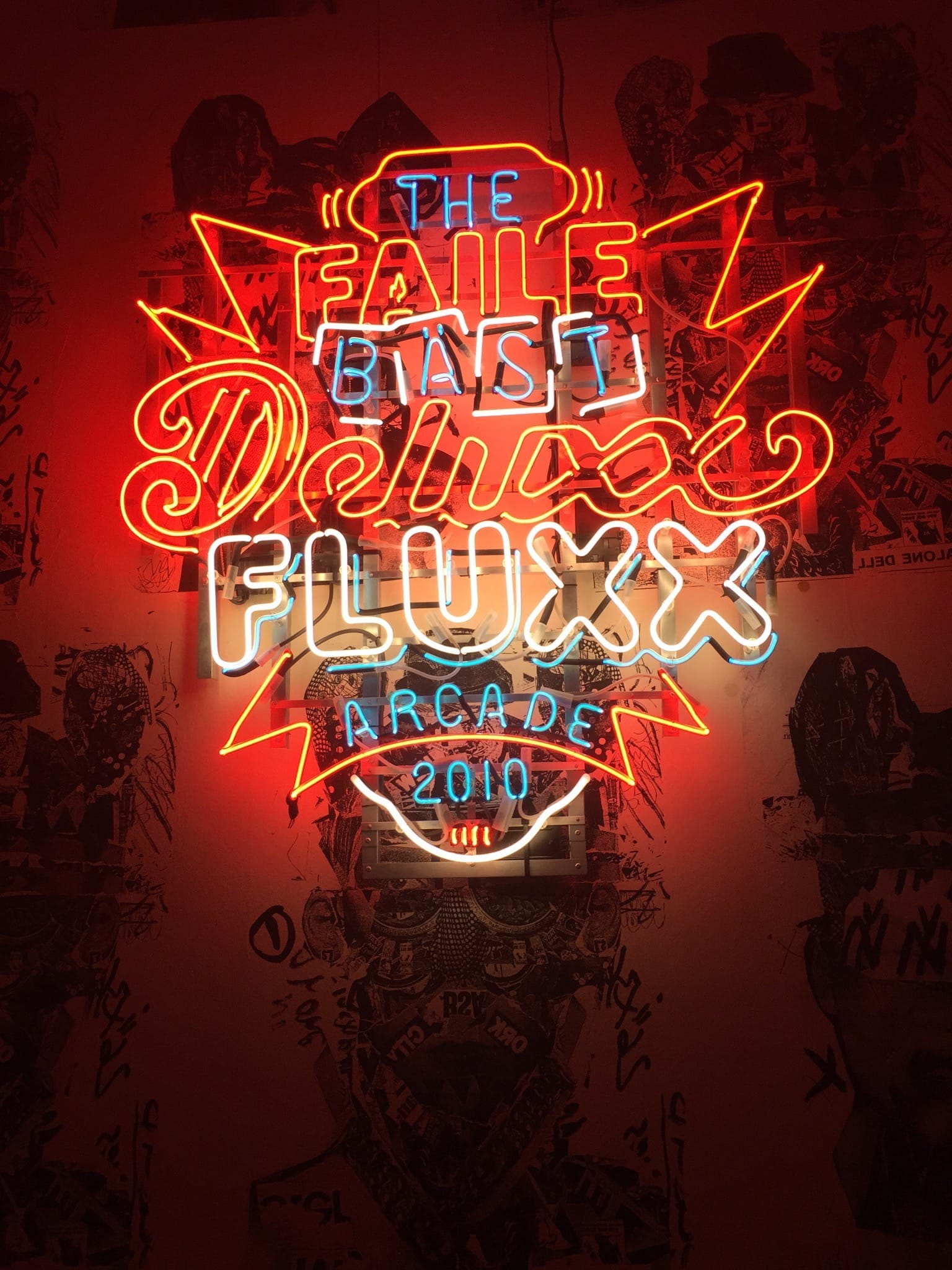

Next, navigate your way through a dimly lit corridor where you’ll find living arcade cabinets, provocative pinball machines, and walls completely covered with the ubiquitous collage art that you only tasted outside. As you step into the last room the images appear beneath you, black lights illuminate the neon-colored-everything-else, including foosball. You’ve just encountered FAILE.

FAILE is an artistic collaboration between Brooklyn based-artists, Patrick Miller and Patrick McNeil. The installation-based series is a fusion of dadaist collaging, pop-cultural appropriation, and street art in the form of interactive media, paintings, sculptures and structures. Each medium appropriates imagery including religious architecture, americana art, comic-book and science-fiction themes, and other “bits and pieces of the past that speak to each other” about contemporary ideas. Miller and McNeil, who met in high school, started collaborating under the name FAILE in 1999, after attending the Minneapolis College of Art and Design, and Fashion Institute of Technology in New York, respectively.

speaking to the ideas of iconography and sacred spaces in historical time

Their latest exhibition, Savage/Sacred Young Minds, at the Brooklyn museum, combines religion, culture and videogames. It helps that the games themselves are a blast. High-Rise Surprise, a button masher where up to six players compete in tearing down brownstones before then constructing high-rise condos to replace them, spoke to gentrification, a very appropriate topic for the borough. Then there was Tunnel Vision Tag, which features you as the anthropomorphic FAILE Dog trying to tag up the subway, dodge ghosts, and find a metro card before the time’s up. The two told me it was very much inspired by Gauntlet.

And I was literally laughing out loud at how accurately Alternate Side Anarchy portrayed trying to park in New York City. In this game, the timer quickly races down as you attempt to maneuver your vehicle into a parking space; it captures the sense of anxiety you feel from that notorious New York City driver in the car behind you, shaking his head and making violent gestures, incessantly railing on his horn. Another game, which seemed bizarre at the time, featured one player driving a car down a road, and a second player controlling a carnivalesque mouth in the distance, producing the road ahead. I came back to it with a friend and we laughed at how pointless it seemed. But perhaps my favorite, due mostly to nostalgia and my appreciation for the absurd, was a Street Fighter-esque wrestling game, complete with teddy-bear Dhalsim.

These works serve as a highly concentrated dose of a particular place and time. The duo has managed to merge street art and graffiti with the more commercial aesthetics of their youth, and approach them from both a high concept, studio art perspective and also a very surreal place. Miller says, “It’s important to see the show and spend time with both the Temple and the Deluxx Fluxx Arcade. They are both speaking to the ideas of iconography and sacred spaces in historical time. We hope that, through the world our art tries to create, people can explore these ideas while directly engaging with the work and leave with a smile.”

Afterward, I sent them over some more questions about the show.

KS: What would you say is the goal or purpose of FAILE?

One thing we try to speak to in our work is the very hunt for meaning in our world. We live in a time where we are bombarded with information and images. The question becomes: How does one personally make meaning in this hyper-saturated world? Given so much of what shapes us when we are young carries through and colors the themes of our adult life. We try to play with that in the work. [We try to] create our own icons and legends, through our artwork, that highlight the ideas and stories that have lived throughout history in storytelling, religion, and mythology. Creating and finding that personal meaning is always important.

KS: What are some of your inspirations?

I think we’ve always been inspired by New York and Brooklyn. We are always observing and documenting the environment around us, the typography on signs and stores, the flyers on light poles, and the way imagery breaks down over time in posters and adverts. We are always paying attention to this. Being young we lived in more suburban areas in the Southwest so many of the things we were inspired by then was found in things we collected. Skateboard and heavy metal magazines, baseball cards, comic books, posters, stickers, and video games. These were the things we were looking at and much of this inspired the way we look at the world today and the way we create in our work.

game design can be beautiful

KS: Growing up did you spend much time in arcades?

Yes, definitely. Arcades are sacred spaces to a kid. You are removed from the everyday world. You are in a place of fantasy and wonder. It’s a full sensory experience of lights, color, and loud music, mixed with sounds from games, the feel of the buttons on the machines, and the way you use them to play the games.

So much of this is disappearing today. We play games more and more in isolated spaces on our phones with no buttons. It’s not a bad thing per -se, it’s just that the game culture that we once loved had places to congregate, and to celebrate them, and also to celebrate playing with each other. It was sacred in that sense as it takes you to another place of being. At least that’s something that we want to let people experience, partially with a nod to history, and then as a way to push it forward, to say “this is art.” These cabinets are sculptural. They are paintings and new media. They are music and installation.

KS: What other kinds of games did you grow up playing? How do you think they affect your design?

Well, we started on Atari and ColecoVision, then Nintendo and forward. So that was happening on a parallel track to playing in arcades. All of those games inspired the way we look at game design today. I wouldn’t say we are pushing anything there. We have fun with the images, the ideas of what the games are saying about a particular place, like gentrification or trying to park in cities. Or just taking stereotypes and subverting the common perception through those games. But the original goal of the arcade was to just give the viewer/player the experience of making art and bringing the art to life, with no objective. No win or lose, just make and play. Over time we’ve evolved into more objective- based gaming, as I think we are naturally inclined to enjoy winning and losing and competition.

KS: Did you create these works specifically for the exhibit, or were they also just games you wanted to make?

Both. We’ve been creating the games in the show for 5 years now. We always want to do more with them but because of time or money we haven’t really gotten to push them as far as we’d like, but we are happy with how they have developed and look forward to continuing to grow them over time.The art becomes alive

KS: Do you feel that games are capable of being works of art by themselves?

Yes, absolutely. I think game design can be beautiful. MoMA acquired the coding of PacMan into the permanent collection from the viewpoint that it is art and I definitely agree. But I think it stops too short. From the look of the game, the art of that, to the cabinets themselves. These are things of beauty and of creative effort. The shape of the cabinet, the buttons, the graphics, and artwork on the side should all be ranked on that level. Pinball machines must absolutely be included in that category as well. These are incredible pieces that should be celebrated as such. It doesn’t quite align with classical art or painting, but as our culture evolves I think more and more people will accept a broadening definition of what art is and how that can be collected and discussed from a curatorial standpoint.

KS: In what ways does interactive media allow you to convey your aesthetic that aren’t really accessible through forms of non-participatory, non-interactive art?

The art becomes alive. The viewer can manipulate the art; they can be a part of the creation process, in a sense. They control it and hopefully have some sense of being the artists and the viewer.

KS: Your artwork has been said to be critical of consumerism, our collective understanding of history, and religion.

For us it’s how you take something sacred— let’s say an icon or image— and how that plays throughout culture, from a revered deity to a beautiful painting or sculptural relief in a church, to the same icon in a garden or fixed to a building, then down to a candle, a sticker and a disposable pamphlet. It’s how all the ideas and images and sacred things of meaning filter down to very disposable, tangible objects. I think to us it all starts with an idea of what is sacred? Where do we place value? What do we covet? And how do those stories, those impulses, become represented in our collective culture?

Most things start with a need or a desire and usually sways through the course of time as being good or evil, and that’s a great starting place to make art from and candles.

KS: Lastly, how is Savage/Sacred Minds different from your previous installations?

The Temple in Savage/Sacred Young Minds was initially inspired by the 15th- century Florentine sculptor Luca della Robbia. His large-scale ceramics were really amazing to us and not something anyone really does anymore. That paired with a lot of research and exploration of castles, monasteries, and churches in Portugal paired with things we were seeing on the street in Brooklyn led to the Temple being born.

The Deluxx Fluxx arcade stemmed from a conversation with our collaborator in that project, BAST. We were discussing ideas for an upcoming show we were doing together which started as a discussion about installations of found furniture and led to pinballs machines and ultimately an arcade. We grew up going to arcades. Playing in them, winning and losing in them and just being absorbed by the space. That is something we feel is lost today and something we wanted to create anew.///

This interview was edited for clarity and length.