The new BattleBots is harder, better, faster, and finally all grown up

To me, the star of ABC’s shiny new BattleBots reboot is neither Nightmare, nor Warhead, nor any of the engineers who grip the controller with white-knuckle intensity and pound on the plexiglass in anger. To me, the star is Wrecks, a robot that’s little more than a red buzzsaw and a pair of awkwardly waddling duck legs. In last Sunday’s series premiere, Wrecks went up against Plan X, a complicated contraption twice its size that came with all the accoutrements of a classic boss fight—two “minibot” clones of itself and a glowing brain. Plan X dominated for most of the match, flipping Wrecks over in classic BattleBots tradition and forcing it to use the saw to move around, its pointless legs pumping helplessly like a flipped-over garden turtle. But then our hero made a huge comeback. “And it looks like Wrecks must have righted itself using the screws to its advantage, Kenny,” one of the announcers enthused. Plan X got stuck for a moment, its minibots swarming frantically; Wrecks slowly loped from the other side of the BattleBox to knock off a huge chunk of aluminum plate armor. Had I been one of the judges, I would’ve given it points for pluck. But pluck is not what they judge, nor does it seem to be what the show or its intended audience are looking for. The categories, in this brutally rational incarnation of the series, are “aggression, damage, strategy, and control.”

Wrecks v. Plan X was both an excellent fight and a pretty good metaphor for the struggle of BattleBots as a show, as it strives to distance itself in almost every way from the self-ironizing BattleBots you might’ve watched 13 years ago on Comedy Central. In the red corner, we have an awkward, barely-functioning tonal hybrid: deadly seriousness flanked and framed by comic devices that point up the semi-absurdity of the whole enterprise. In the cold, efficient machine-glow of the blue corner, we have the BattleBots of the future: an assemblage carefully engineered to be the object of serious, invested spectatorship. In the red corner, we have Carmen Electra interviewing bearded dudes from backwater Wisconsin, Bill Nye providing “expert commentary,” and sketches about robot cats. In the blue corner, we have stratospheric production values—“Spare no expense,” some John Hammond at ABC must have said—and a constant litany of straight-faced, amped-up pronouncements. Even the inevitable robot puns are somehow uttered without cracking a smile. “They have poured blood, sweat, and gears into their creations,” says the aforementioned Kenny, also known as “MMA star Kenny Florian.” “And now it’s time for survival of the fittest.”

an unspoken ban on robots that are pure wedge and nothing else

Aficionados of the original show will find the basic premise almost completely untouched: two remote-controlled robots fight to destroy each other in an arena filled with hazards, including saws that rise up from the ground and oversize hammers of Thor in every corner that can be controlled by the opposing team. If a match doesn’t end in a knockout (which happens about 50% of the time), the judges weigh in to determine which bot was more aggressive, damaging, etc. Attempts have been made to address certain balance issues. As in the MMO, what began as a limitless field of possibilities eventually devolved into endless variations on three familiar, ossified archetypes: the wedge, the lifter, and the spinner. In theory, they were locked in an eternal, rock-paper-scissors-like triangle of mutually assured destruction—lifter beats wedge; wedge beats spinner; spinner beats lifter. In practice, the simple, rock-like wedge had little trouble beating pretty much anything, which led the producers of the new season to introduce special anti-wedge pistons that pop out of the arena floor. More importantly, it appears that they’ve instituted an unspoken ban on robots that are pure wedge and nothing else. No robot shows up to the arena without roughly 50% of its body mass devoted to some kind of weapon.

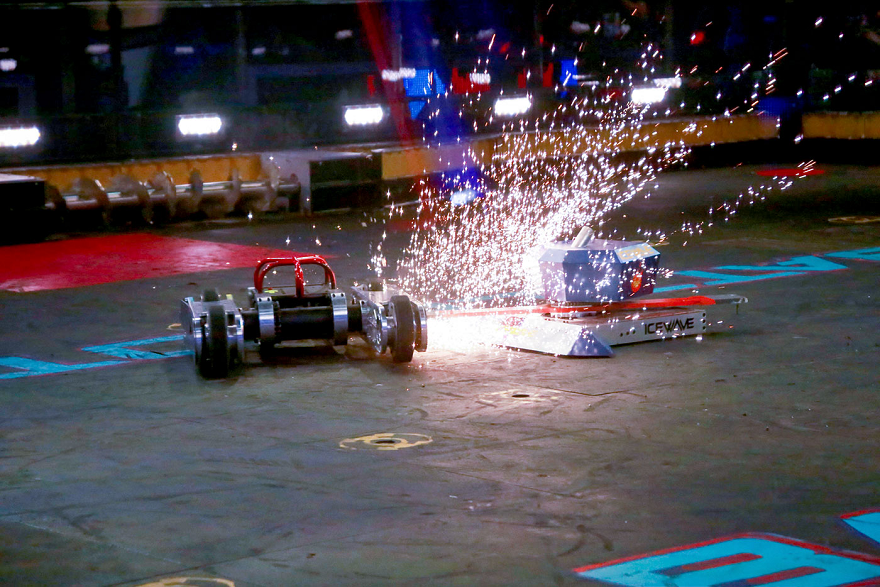

If the core content of BattleBots is more-or-less the same as it ever was, the way that content is framed for the spectator has been almost completely transformed. Gone are the wisecracks of the Sklar brothers as they interview an untelegenic hobbyist holding a severed piece of scrap metal; gone are the celebrations of destruction for destruction’s sake. Now, men wearing well-cut suits debate the relative merits of IceWave v. RazorBack, and fights are interspersed with impeccably well-shot backstories that give them human stakes. “I grew up with a single mom,” one engineer tells us. “My dad passed away when I was 10. I had to find ways to entertain myself.”

The new BattleBots is infused with professionalism and a sense of purpose, fueled partly by the egalitarian rhetoric of esports, which wasn’t nearly as pervasive back in 2002. Here, the show proclaims, is a serious form of competition that does not exclude people on the basis of anatomy, explicitly rewards creativity and innovation, and manages to satisfy the audience’s desire for gladiatorial carnage. “I’m not some 35 year old man. I’m not the average programmer. Building robots is for everyone,” says Lisa Winter, Plan X’s designer, a young woman who’s been in the BattleBots business since she was 12. The mere fact that she invokes a 35-year-old programmer as the stereotypical BattleBots athlete says a lot about the sport’s potential inclusivity; if you see a lot of pudgy dudes on this show—and, spoilers, you will—it’s because of the gender imbalance of the tech world rather than the nature of the sport itself.

The tonal shift is welcome, warranted, probably necessary. An extensive oral history of BattleBots at SB Nation makes it clear how much the producers believe that Comedy Central distorted the show’s ideal formula in their relentless pursuit of the 18-24-year-old male demographic. “It was all tongue-in-cheek,” said producer Marc Thorpe, whereas the series of original mid-90s competitions in San Francisco that pioneered the whole concept, Robot Wars, “was genuine, there was no bullshit.” Comedy Central executive Debbie Liebling charitably described it as “sort of a parody of a sports show without being a parody, because it delivered the real goods of competition at the same time.” Co-creator Trey Roski less charitably recounted how “they kept on throwing bigger and better hot babes at it. We gave them notes, but they rarely listened.” The old BattleBots looked like something beamed in from a Mad Max future of crude welding, clanking metal, and sexual exploitation; the new version attains a measure of dignity from the get-go by aping the conventions of sports shows without satirizing them and conveying a futurist message that actually rings true.

There was a familiar atmosphere of irreverent pointlessness and unchecked testosterone

At the same time, I think its predecessor is worth remembering, if only for one reason: it was painfully, fundamentally awkward. It was as awkward as Wrecks. It was as awkward as any preteen who might’ve tuned in at the time, myself included.

///

Throughout the entirety of middle school and a good chunk of high school, Comedy Central was my after-school program. I came home every day to Win Ben Stein’s Money, a misanthropic and deeply strange game show in which a much fatter Jimmy Kimmel insulted every contestant. I stayed for pretty much everything else the channel would air: The Daily Show; Whose Line is it Anyway?; reruns of Conan and Scrubs; South Park; Crank Yankers; endless showings of Robin Hood: Men in Tights. In a lot of ways, I credit the network for shaping my sensibility, but I think what it really gave me was exterior rather than interior: a carbon-fiber carapace woven from cynicism, irony, and dick jokes. I used it to ingratiate myself with the cool kids; I used it to hide; I used it to feel the security of an identity, even though my identity was in flux. When BattleBots came along, the show connected with me in part because the network had taken pains to make it fit within the Comedy Central multiverse. Open a door at the end of the BattleBox and you’d find yourself on the set of The Man Show. There were familiar faces. There was a familiar atmosphere of irreverent pointlessness and unchecked testosterone.

But there was also something different about the show. At its core was an indefatigable earnestness: grown-ass adults laboring in their garages to make Death Roombas and hydraulic pickaxes; names like BioHazard, Backlash, and Toro (my personal favorite) chanted fervently, sincerely, by hundreds of fans; the halting, jerky movements of claptraps running on diesel. At its core was a weird, nerdy subculture, not entirely ready for TV and thrust onto TV before TV itself was ready to become a subcultural buffet of hoarders, polygamists, pickers, extreme couponers, and duck dynasts. I don’t think I was alone in having two parts of myself that were into BattleBots at the same time: a part that wanted to create, left over from my LEGO-building childhood, and a part that wanted to destroy. The show was not complex, but in retrospect it appears to have been a fairly accurate mirror of a middle-schooler’s mind: hardened cynicism wrapped around a gooey, vulnerable center.

Above all, the difference between old BattleBots and new BattleBots is a matter of self-confidence. In the new season, there are as many contestants from random backwaters as there are from academic programs and Silicon Valley startups. The idea of gladiatorial robot competition now enjoys institutional and cultural approval, which was not exactly the case in 2000. Fans of Big Hero 6 may remember how the film brands underground robot fighting with the seal of immaturity. It’s a cash-only, back-alley kind of thing that the 13-year-old protagonist, Hiro Hamada, does before he realizes that he should go to college and apply his talents to something that might benefit society. But the fact remains that robot fighting is something one can do in San Fransokyo. It’s a place where one might start. The film depicts it as a gateway drug that leads to innovation—apply the same skills elsewhere and you’ll win TechCrunch Disrupt. The new BattleBots, just as attuned to the tenor of contemporary futurism and STEM-kid fetishism, makes a similar promise to its contestants and its audience. “This is no exaggeration bullshit,” producer Greg Munson told Fast Company. “The people in this room are the people who will … inspire the people solving the problems of the world.”

BattleBots left us when it was a snarky 12-year-old

“They play at the intersection of design and destruction,” the announcer proclaims. “Design” is a keyword the show never really got to use before.

The saga of BattleBots presented by the show’s creators is one of corporate mishandling and tragic incoherence. Comedy Central didn’t know what to do with BattleBots, so they surrounded the core combat with layers of irony and cheap pandering that distorted its basic premise. Surely we should assume that they’re right about their own creation. But I can’t help but wonder if the tone wasn’t also a form of self-protection, whether anyone intended it to be or not: a cynical shell to protect an earnest center; a regime of self-irony to protect a vulnerable self; a chrysalis for something still in development, not ready for the outside world.

BattleBots left us when it was a snarky 12-year-old, cracking robot dick jokes to mask its existential insecurity. It returns to us an adult, mature and confident in its mission. The people who give a shit will say that it never should’ve been self-parody; what we get now is what we should’ve had all along. I wonder if that’s really the case.