The new mundanity of space games

The conference floor was full of astronauts, engineers, and students. Bodies quickly filed past each other to find an open seat. My team of 4th graders waited impatiently to sit. Before I could join my fellow classmates, a hand reached out to guide me to a new seat, away from the others. Instead of sitting a few rows back, I was ushered toward the front. Next to me was John Glenn. Former astronaut. The first American to orbit the Earth. Fifth man to travel to space. I stared up at him in awe. He’s been to outer space. I want to go there too. He noticed me and smiled. The lights dimmed and a presentation about the Mars Rover began to play. Space Day 2004 had approached lift off.

///

NASA’s Space Day is an educational initiative designed to encourage students to pursue careers in STEM. I was 10 years old when my teacher Ms. Voigt announced the competition to the class, and through her encouragement seven students, including myself, decided to enter. There were several different categories to choose from, but we decided on the Space Trek challenge. The prompt was to keep a fictional log detailing our day-to-day lives on the moon. More specifically, how we fared inside the crater Copernicus. Our team was named the Crescent Craters.

We documented our progress on a website we made with the help of our teacher, and described everything from the surface temperature to how fast the lunar rover vehicle (“moon buggy”) traveled that day. We drew comparisons between exploration of the moon to Robert Peary and the North Pole. We tracked the phases of the moon and recorded our findings. Because we were allowed creative freedom, we mapped out the logistics of creating a retreat on the moon for Earthlings. I took things one step further and convinced my dad to buy me a telescope. We went to the local planetarium so that I could see all of the constellations and learn their names. I would clip out newspaper articles announcing the date and time of asteroid showers and beg my parents to let me stay up late enough so that I could watch.

If I couldn’t physically go to space myself, then doing it virtually was the next best thing

One day, Ms. Voigt asked my team and I to stay behind for a of couple minutes after the bell rang. She told us excitedly that we had won the Space Day challenge. The following weeks were a blur. Our small town was proud that a group of local kids accomplished something that would garner the attention of larger communities. The newspaper wrote a few pieces about the winning teams and took photos of all of us. I still have copies hidden away in a box, given to me by delighted family members who supported my dream. Space Day was a big part of my identity at that time.

When I started 5th grade the following year, it became apparent that my academic weaknesses would squash the expectations I had for a career in space. While my level of reading and writing surpassed those around me, I was tutored after school in math because it was my weakest subject. I loved science, but the older I got, the more its concepts flew over my head. Middle school had students take standardized tests that would give them an idea of what their career path would be. My results told me I’d be a firefighter. Disheartened and lost, I stumbled into high school, abandoning the idea of leaving this planet through means of rocket propulsion, and spent my formative years drifting without a purpose.

///

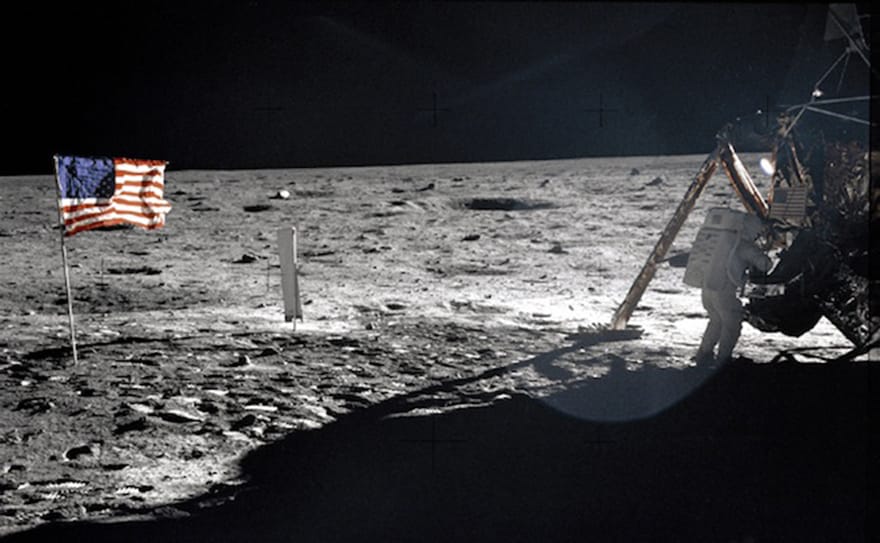

The idea of human space exploration is enticing even to those of us without the necessary skills required to become an astronaut. Science fiction has given me a romanticized insight on our universe and my place within it. I’m fully convinced that there are other forms of intelligent life (aliens) that share the galaxy with us. Although science fiction has no grounds in reality, it still fosters the curiosity and excitement that my dad felt as he watched the moon landing from his television in 1969. That said, technology is increasingly in a position to turns dreams into reality. Nowadays, society’s dream of going to outer space is being achieved in a variety of ways—thanks to the easy accessibility of the internet and emergent technologies.

Videogames are, of course, one of the more popular conduits for achieving this goal. It should come as no surprise, then, that during my time of uncertainty in life, I discovered the Mass Effect series. It was then that my fascination with games that allowed me to be among the stars manifested. If I couldn’t physically go to space myself, then doing it virtually was the next best thing. What particularly grabbed me about the first Mass Effect (2007) game wasn’t the interactions I had with companions or the futuristic combat and advanced technology. I loved and consequently paid high attention to the spacecraft, interfaces like the galaxy map, and the engrossing world of its space politics. These details provided the kind of ordinariness—a sense of daily life—in outer space that made sense to me.

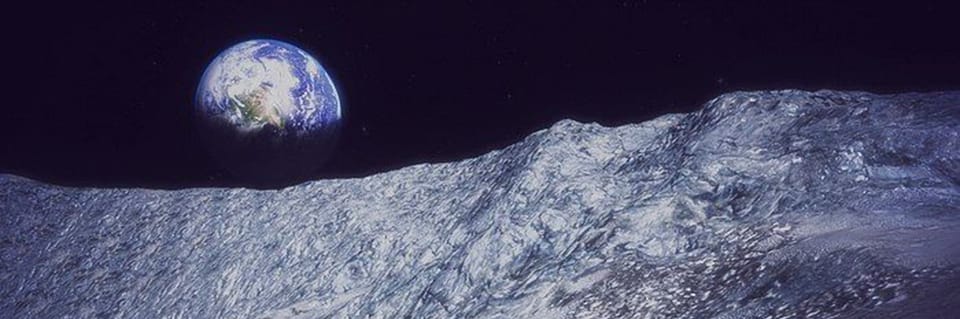

The SSV Normandy was a big part of the game’s success for me. Significantly, it’s a vehicle crafted by a collaboration between humans and aliens, and houses your entire crew. The presence of the crew being everyday people, unlike the battle-ready soldiers that star in the game, appealed to me. They maintain system operations and talk with each other. Being able to walk about the cabin and examine the quarters and the dining hall made the experience feel more plausible. Using the galaxy map to leave the Normandy and explore surrounding planets feels bare, as most of the new worlds look the same visually. But it offers the opportunity to put a helmet on and rely solely on an oxygen tank. Through Commander Shepard, you’re able to set foot on Earth’s moon. You can glance up at the darkness and take it all in—your home planet staring back. But, for me, this is where the illusion ends, because as you walk on Mass Effect’s facsimile of the moon, dust isn’t kicked up at your heels. Neither do you bounce around in the low gravity. Footsteps don’t leave imprints. I was taken out of the experience, only to realize that this made me want a better representation of space travel.

Naturally, I have taken to seeing what other means including other videogames are available to bring people closer to the mundanity of space. If you stick with videogames, there are potential options such as The Fullbright Company’s Tacoma, which will take place on a space station and feature zero gravity movement. Instead of interacting with aliens, you’ll be left to piece together information about the previous crew members who once lived on board. In avoiding the wilder temptations of sci-fi, Tacoma looks to depict a reality that could plausibly occur in our future, one that looks to the ghosts of technology that we leave behind today. Adr1ft by Three One Zero (also available in VR) is another interesting approach that tasks you with exploring the wreckage of a destroyed space station, but you do this while fighting for survival as your EVA suit leaks oxygen. It’s an effort that brings to the fore the unforgiving nature of space; the fact that we are not built to survive its vacuum.

society’s dream of going to outer space is being achieved in a variety of ways

You’re left to float helplessly among the wreckage, taking in the severity of the situation while also gazing upon the Earth looming in the background. It encapsulates the fragility and beauty of spacewalking that we can only read about in the written memories of astronauts. Perhaps, with the addition of VR, you can actually get the feeling that you’re floating. But why stop there when private companies like The Zero Gravity Corporation exist? Using a specially modified Boeing 727, the company can fly you high up and then let the shuttle freefall to achieve a momentary weightless environment, allowing you to float as if you were in space. If you’ve got the funds for it ($250,000) there’s also Virgin Galactic, a spaceflight company that is developing commercial spacecrafts to provide sub-orbital spaceflight for “space tourists.”

No Man’s Sky should be unprecedented in its ability to let us ordinary folk explore space and discover new planets. And while this is epic in every way, what stands out the most about the game is how routine it aims to make the experience. You fly from planet to planet, charting their lands, their creatures, and pretty much everything else you see. It’s a game that turns you into an intergalactic scientist who, unlike those in Mass Effect, charges in with a clipboard rather than a gun. You become like one of the many people staring up at the night sky through their telescopes, acquiring a wealth of knowledge about the unreachable, except in No Man’s Sky your faraway subjects are reachable. Expect screenshots from the game to emerge like the photos on this website, which contains pictures taken by the Hubble telescope. There are different albums that feature everything from galaxies and their sub-categories to nebulae. Each album contains pages upon pages of what is naked to the human eye. The shots are breathtaking.

No Man’s Sky also makes an effort to leave in every detail in its simulation of space travel. You’ll be sat in the cockpit with a full view of your ship’s interior. As you fly into a planet’s atmosphere and look from the window, you’ll be able to see the clouds breaking apart, and watch as bits of rubble fly past your view. Its greatest hit might be that it’ll provide seamless transition from orbit to landing—not a loading screen in sight to take you out of it. Modifications and upgrades can be made to your ship too, allowing you to act as a fighter, a trader, or to preference stealth, speed, and interstellar exploration. Kerbal Space Program (2015) has already taking this engineering fantasy further as it tasks you with creating a vessel that can guide your team to new worlds. When constructing a space craft, each piece must be assembled carefully—each part has a different function, which could impact the way a ship flies or fails. Appropriate physics ensures that if you design a bad ship, it will crash. If successful, you can navigate to distant moons, asteroids, or planets. Despite your crew consisting of members of a tiny green species known as Kerbals, the customization and freedom to build and explore space on your own terms is freeing. NASA feeds that same fascination through software that is open source and featured on GitHub, allowing those who are interested in the technical aspect of space to see what programs are used for what and how. Then there’s the Mars One initiative, which is a not-for-profit foundation with the goal of establishing a permanent residence on Mars. But perhaps more interesting than that to wannabe astronauts like myself is that Mars One will recruit ordinary people to become a Mars One astronaut, provided that they make it through a selection process of four rounds.

To go one step further and really emulate being in the shoes of an astronaut there’s Lunar Flight (2012). It’s a lunar landing simulation that has you transporting cargo and acquiring data at survey locations. To add tension, there’s limited fuel in the lunar module which provides a sense of urgency to your carefully calculated actions. It recreates the kind of anxiety one might get from watching the Mars Rover landings. Will it be a success or a failure? Which then becomes: am I a competent astronaut? It’s the question I’ve avoided the answer to for years now, perhaps hoping to find it through these space travel surrogates—as if I could ready myself for the job of an astronaut by artificial means.

///

I walked through the crowd of engineers and astronauts at NASA’s Space Day with goodie bag in tow, weaving through all of the space-related stations on the event floor. There was even a machine similar to an aerotrim that kids could be strapped to in order to experience a more forgiving, less vomit-inducing look into astronaut training. There were models of previous rovers and space shuttles to look at. I ate freeze dried ice cream from a silver bag. But more importantly, I got to speak with someone who was going to be sent into space. Soon. I don’t remember much, but he was tall and answered all of my childish questions with a smile. He signed the back of my t-shirt along with his fellow graduates. The shirt is safely tucked away in a box in my closet. It’s the closest to space I got.