Nina Freeman’s anime sex quest

Header illustration by Jordan Rosenberg

///

If real life were like anime, the first shot introducing Nina Freeman as a character would be a slanted close up of her big, bright, transparent eyes. Then maybe a slow pan up to the bubble gum pink hair, before a sudden cut to some awesome action shots—like her throwing a fist up into the air, leading an army of female programmers into battle under a Code Liberation banner.

Or, you know, something like that.

Beginning a profile on Nina with make-believe anime stuff feels like the only appropriate way to do things. Because, arguably, that’s exactly how her career started. “I’d roleplay a lot with my friends as a kid. And now I realize we were basically just LARPing our favorite anime or videogame characters at the moment. Like, when Final Fantasy X2 came out, we would all run around and I’d pretend to be Rikku, my friend Britney was Yuna, and her twin sister Melanie was Payne. Actually, those two went on to become game designers too.”

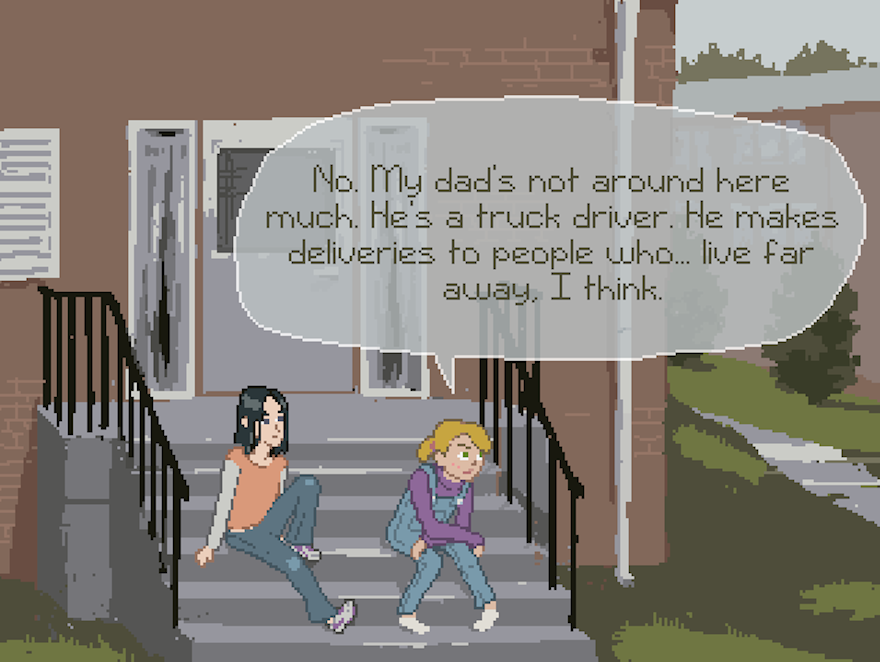

Shortly after ending her period as an intern at Kill Screen (where she did a couple pieces of freelance writing as well) Nina released how do you Do It? in collaboration with Emmett Butler, Deckman Coss and Jonathan Kittaka. Reading almost as an homage to the importance of early roleplaying in her own life, how do you Do It? places the player in the shoes of a young girl, whose mom has just gone out. So, obviously, the first thing she does is run over to her play area, disrobe two Barbie dolls, before fervently smashing their non-existent genitals together until Mom gets home. It’s an activity everyone who had access to dolls and even the slightest notion of what “kissing stuff” meant while growing up will recognize. And it probably taught you a lot more about what sex did to you than health class sophomore year did.

For Nina, acting things out through play introduced her to an experience of empowerment and discovery that only narrative exploration could. “It gave us a sense of ownership over the stories,” she says about her backyard LARPing. “That I could go off and bring these characters into the real world, make them my own, and live vicariously through these stories.”

It fostered not only a love for games and anime, but also an orientation toward vignette-style character exploration, whether in poetry, theater, or game design. Most of Nina’s games are born from an idea she gets about a distinct memory, or an exchange she remembers between her and another person that left an impression. “It’s really about boiling the mechanics down to one core interaction that’s only there to communicate something about a character,” she explains. “And all my games are basically about myself. I try to get people to understand my self. And the way I try to communicate to the player that they’re playing me as a person is by putting them in these very specific scenarios, with very specific details.”

Detail and context are key to the type of character exploration Nina aspires toward in her games. “I try to give people as much context as possible because when people don’t have enough context, they’re preoccupied with trying to understand the situation. But if you give them just enough, the suspension of disbelief takes over and they can play the game as it is.”

People want to hold onto each other, and know that they’re not alone in the world.

In how do you Do It?, for example, Mom leaves and the player is instantly brought back to that moment in childhood when their house became suddenly rife with possibility. There you are: all alone. And when the two naked Barbie dolls are revealed, the protagonist’s face pressed up close against your screen, you can’t help but see yourself in her. A sense of giddy nervousness sweeps over you as you worry about your mom coming back—thoughts meandering to that steamy car scene in Titanic.

When I first played how do you Do It?, I didn’t know how to react to the intimacy of the experience. It felt too revealing, of both myself and the game designer. For a split second, I resisted it, unaccustomed to feeling so… found out by a game.

That’s a characteristic of all Nina’s work. It’s not interactive fiction, nor does it feel in any way an interrogation into the “interactiveness” of the medium. While usually brief, each one of Nina’s games manage to utilize a (by all means simple) mechanic to communicate something I’ve never seen addressed by the medium, successfully or otherwise.

Because while big studios are still dodging depictions of sex until avatars start looking like something other than two dead fish slapping together, how do you Do It? provides an exploration of early sexuality that actually utilizes graphical crudeness to its advantage. “Games are definitely a great medium for exploring sex,” Nina asserts, as a vocal advocate for intimacy in the medium. “Having sex is, in a lot of ways, an act of discovery. And with games, it’s always a learning experience, and through that comes these similar feelings of discovery.”

Like roleplaying Final Fantasy in your backyard, Nina’s games provide safe, innocent spaces to explore a simple interaction between you and the fiction. Yet somehow, through that interaction, the fiction becomes less about itself or even the story, and a lot more about you. “I try to just express the story rather than putting too much of my emotions into it,” Nina says, which can sometimes be difficult when all your games come from a deeply personal place. But ultimately, although Nina enjoys the catharsis of making autobiographical games that invite people to accept who she is, she says, “I want the player to be able to explore the emotions on their own.”

A lot of the success of these simple yet central interactions (like smacking non-existent Barbie doll genitals together), which are such a marker of Nina’s games, stems from that personal process. An inward understanding, from a memory or a relationship, is distilled into a mechanic that’s projected outward onto a screen. Through the poignancy of that mechanic, the understanding manages to work itself into the player through discovery, devoid of any great imposition from the creator. As with most good art, the specificity of these interactions and scenarios allows the emotions to speak for themselves. The universality of the human experience takes over, no further editorializing needed.

“I want the player to be able to explore the emotions on their own.”

“That’s why I love these cathartic, autobiographical games so much,” Nina says. “People want to hear about reality. People want to hold onto each other, and know that they’re not alone in the world.” And games, though often saturated in meaningless fantasy simply to support unrealistic mechanics, have all the potential in the world to do that for players.

Going forward, Nina will be finishing up her grad degree in the next year at NYU’s Polytechnic School of Engineering with a master thesis that will be her most personal and autobiographical game yet. Cibele (which she will be releasing with a group tentatively calling itself Star Maid Games) tells the true story of a teenaged girl who meets a boy online in an MMO, falls in love, and has sex with him. “A lot of people have had online relationships, but no one talks about them,” Nina says, admitting to her own initial hesitation over revealing a story she’s carried a lot of anxiety about for years. “I hope this will start some of that discourse.”

Online culture has irrevocably changed how we experience sexuality, but as a culture we’re only just starting to acknowledge what that means. “When I had never had sex and was literally thirteen, I would go on AIM chatrooms and watch people have cyber sex. I think I even tried it once and got too freaked out and left,” Nina admits with a laugh. Yet instead of all of us sitting down and talking about that reality, the only discussion on the subject I can summon up is newscasters warning parents about their kids potentially sexting. “Our tech culture is just so saturated with sex. We can’t even avoid it—I mean there’s more porn on the Internet than anything else. It’s almost like you’re seeing and hearing sex all the time, but not really experiencing it until it happens. And I feel like it almost makes people have this sort of hysteria over it.”

In a lot of ways, games may be the medium most fit to counteract a kind of hysteria that stems from a lack of experiencing something. As Nina says, “it kind of just shows that if there is a method of communication, humans will always find a way to use it in order to have sex. Yeah, that’s definitely what it proves.”

Throwing out all pretenses this time around, the protagonist of Cibele will be named Nina. Real life Nina has already started recording some of the voice acting for it, which she describes as an odd experience, “because I’m writing the lines I remember having said, then having to perform them. So I’m actually performing something that happened to me in real life.”

Funnily enough, that sounds an awful lot like a complete reversal of her early, formative experiences, like LARPing in her backyard. Back then, Nina used to take fiction and perform it until it resembled something closer to her real life. Nowadays, she seems content to perform real life until it resembles something closer to fiction.

Though, of course, Nina isn’t ever above some more Final Fantasy LARPing.