You are a school principal. You see a student who is being bullied. His parents ask for you to keep an eye out on him, make sure his feelings aren’t hurt. There will be hell to pay if he is sad when he goes home. You could stop kids from picking on him. Or you could help his self-esteem. But the easiest way to not get an earful from the student’s parents? Have his teachers use lasers to turn him into a pineapple.

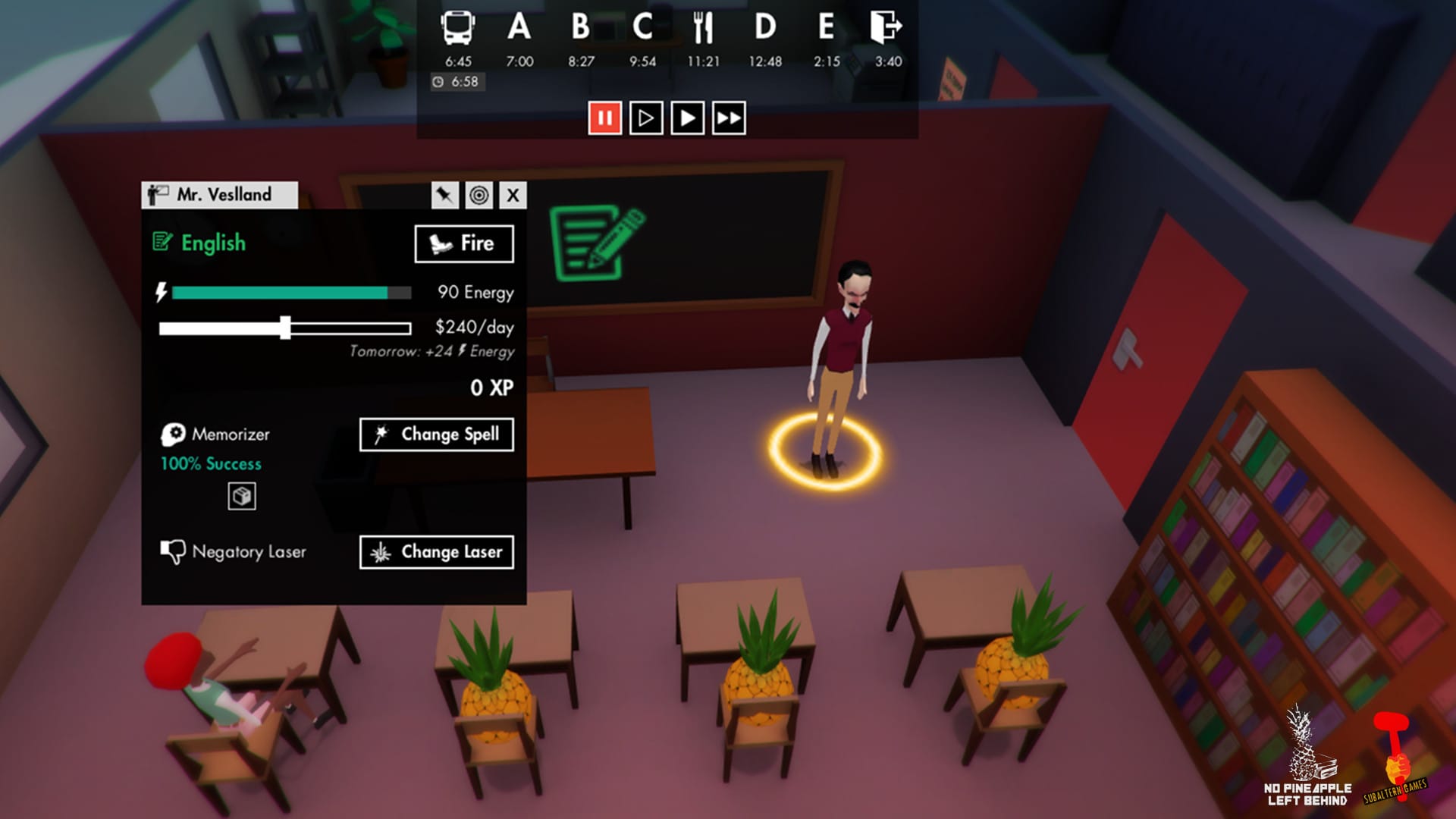

In No Pineapple Left Behind, from Subaltern Games, you play as this peculiar principal. You have to juggle the responsibilities of supporting teachers, improving students’ grades, and managing a budget. This is quite a job, where accounting for every dollar of your daily spending allowance becomes crucial. It is much easier to resort to your magical power, which drains the humanity from kids, turning them into pineapples. The titular fruit has no feelings or distractions. They just learn. If only real life were as easy.

THE TITULAR FRUIT HAS NO FEELINGS OR DISTRACTIONS. THEY JUST LEARN

As the title suggests, No Pineapple Left Behind is a satire of the “No Child Left Behind Act” of 2001. The concept of this act is to punish schools that aren’t performing well by reducing their funding. Many claim that the result has been an education system geared solely towards passing the tests used to measure performance, rather than teaching subjects fully. Some teachers have even been caught cheating for their students, hoping to ensure they have bigger budgets to teach with down the road. It’s an imperfect solution for a messy system.

No Pineapple Left Behind creator Seth Alter, a former teacher, used the frustration he felt from his time in front of the classroom to fuel this latest game. He pipes the frustrations he experienced during that former job into a game is both silly and critical. The blows that Alter delivers to the school system tend to be heavy-handed. In No Pineapple Left Behind, children have a humanity rating, and as they learn and grades go up, it automatically goes down. When it hits zero they become pineapples.

This isn’t as alarming as it reads: the game is presented with its tongue firmly planted in its cheek. The title screen looks like Soviet-era propaganda. The music feels like a militant march. The lesson names, like “Invisible Hand’ and “Trigonomancy,” as well as teacher’s laser attacks, like “Cheating Bolt” and “Unfriender Nova” are meant to make you smile. The levels in this magical world drive the satire home with their amusing obstacles: child tardiness due to teleporting buses running late during a drivers’ strike, or overcrowding because a wing of an underwater school is being flooded. The children talk to each other with emojis and messaging language like “U SUX.” There is even a game called Fruitbol. Turning kids into pineapples isn’t so outrageous among all this.

As a principal, however, you’ve got to keep a straight face, working towards increasing students’ grades (and decreasing their humanity). The higher the grades at the end of the day, the bigger budget you have for the next day. The result of this system is micromanaging every aspect you can, switching lessons and educational materials between classes, zapping students with lasers to dehumanize them or to end their distracting friendships. It’s a lot of work, and students can still fail to learn the lessons taught, their grades going down (and humanity going up). Often, it is easier to have a teacher zap the children into pineapples, then push to reach the high grades you need to finish a level or to earn more money. Reduced to objects, the students can be approached purely analytically, fixed with just the right approach, all without the messy empathy or complexity that dealing with people requires. Morality be damned.

MORALITY BE DAMNED

But adjusting teachers’ situations continuously exposes another challenge of the game, which in turn, reflects another of the difficulties of real world education. The more money you give teachers, the more energy they get back overnight to fuel the next day’s lessons. In the beginning, a teacher only has a class or two, but that grows to five per day. Teachers can’t lead five classes and give their all for every single one. Some get crappy lessons to conserve the teacher’s energy. Inevitably, you hit a moment when it becomes cheaper to fire your teachers and hire new ones than to pay your burned out teachers to come back the next day. The grim fact you learn is that overworked teachers, driven by your own whip, are not as effective as those that are not—there is no mercy when money is the ruler.

Pulling back from these finer details, No Pineapple Left Behind is divided at the macro level into different schools in the different neighborhoods of the fictional city of New Bellona. Each school is a level with specific objectives to meet, such as reaching a $1000 surplus in one week, or avoiding going bankrupt in a period of two weeks. Surviving the typical grind of the game is difficult enough but the later challenges become gruelling. Add parents complaining, along with budget penalties if you don’t address issues like students being teased or grades not going up, and succeeding in managing a school becomes a nearly impossible task.

Unfortunately, No Pineapple Left Behind, in satirizing a long and tedious job, becomes one itself. The daily routine of pausing to adjust a teacher’s lessons and materials, unpausing so a class occurs, then pausing to reassess and readjust for the next class, and then repeating all that for each class, while strategically shooting lasers to turn kids into pineapples; it wears you down.

The systems of the game are interesting at an intellectual level, good for discussion, but they aren’t compelling to play with. Yes, the game succeeds in showing that the only strategy to be a good principal in such a system is to fire new teachers instead of bringing back veterans. It displays that rigid education can dehumanize students. And it shines a light on the ridiculous juggling a principal has to do to keep it all afloat, and does it in a somewhat amusing way. But it is a satire that becomes increasingly hard to appreciate the longer it goes on.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.