A hypothetical scenario: someone arrives at the ballot box on election day without knowing much of anything about the candidates. They don’t have a real basis to vote for anyone—no understanding of what these figures hope to accomplish if elected—but one name in particular stands out as more familiar than the others. It conjures up a vague recollection of a campaign poster, a TV ad—something lends a faint tinge of good vibes to the candidate’s name. That’s who the uninformed voter chooses.

As made clear by a relatively unknown, but confident Kennedy charming his way past a sweaty, TV-unfriendly Nixon, understanding how to properly manipulate mass media has always been instrumental in political success. A good smile, a solid photo-op, and a memorable sound byte—these are often a modern political campaign’s defining (and ultimately inconsequential) moments.

a tone of apathetically considered violence

And so we have, BunnyLord, the large, purple, barely bunny-ish set of suit-wearing pixels who bookends Not a Hero’s hyper-violent missions by nonsensically rambling about his need to win the upcoming election for mayor of an unnamed English city. BunnyLord is bound and determined to triumph and—despite being more than willing to direct his supporters to brutally murder his riding’s gang members—completely dedicated to the democratic process. He’s seen the future, BunnyLord, and insists, in the grand tradition of so many real-world politicians, that something monumentally awful will happen if he doesn’t win. So, he seeks to appeal to the public by enlisting (mostly) blue-collar toughs to “crack down on crime” by blasting away (mostly) foreign gangsters. The Russian and Japanese mobs must be eliminated. The drug dealers must be driven out of the council flats they control.

There are a number of gunfolk for the player to choose from, and more to unlock as the mayoral candidate’s approval rating rises. The characters range from a shotgun-toting Glaswegian dressed in the trucker hat and hunting vest of an American hillbilly to a chain-smoking Englishman who wields dual pistols in acrobatic, Chow Yun Fat fashion. These are BunnyLord’s supporters: the women and men who, for whatever (likely monetary) reason, want to help him become mayor by serving as trigger-happy campaign aides. After a briefing, in which BunnyLord outlines the mission objective (always a variation on who to kill and what to destroy), the player chooses one of the available characters and is dropped near the entrance to some assortment of multi-storied residential or industrial building.

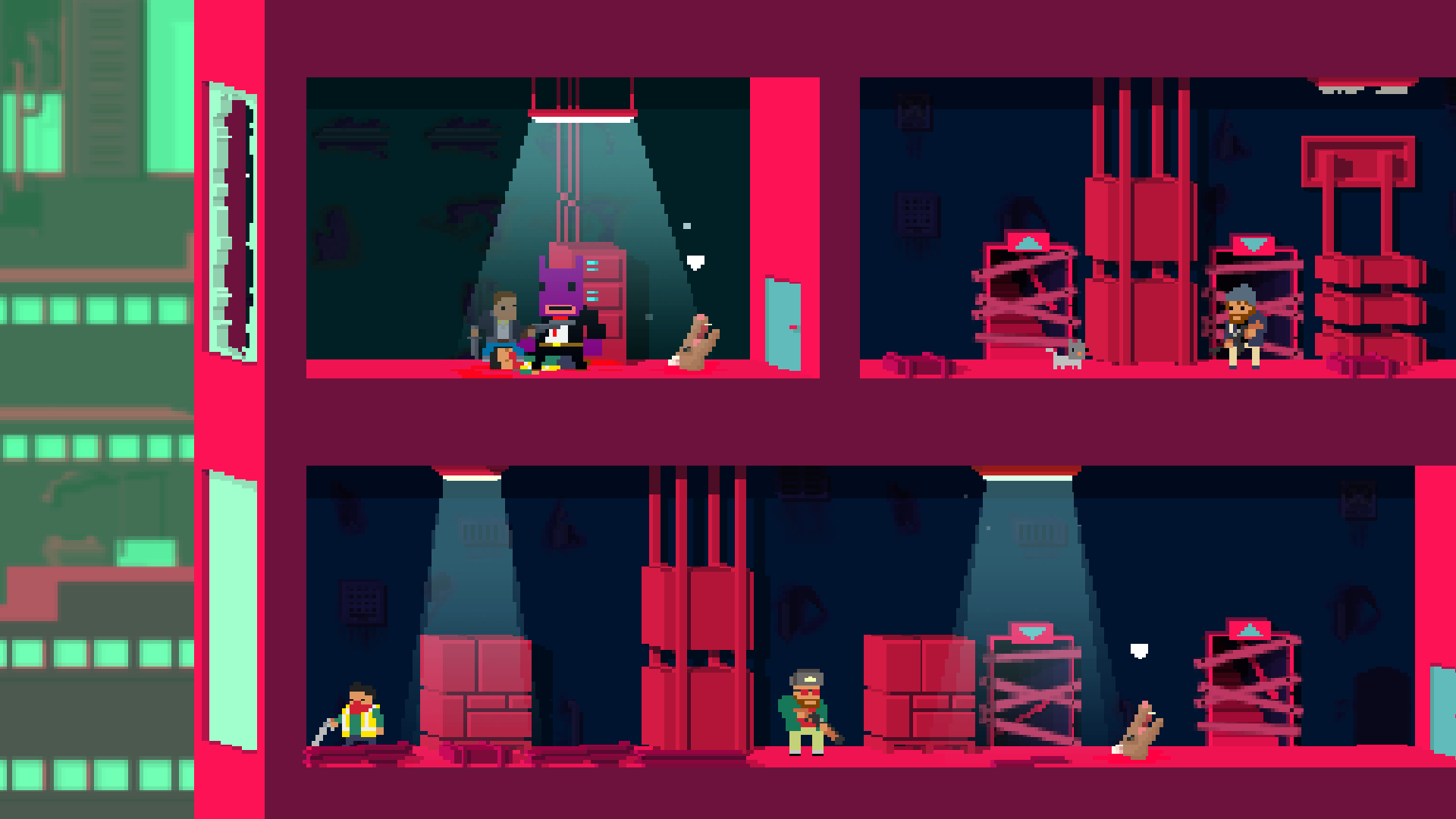

The levels consist largely of hallways, presented from a zoomed-out, cutaway view that exposes networks of staircases and doorways in which to traverse the environment and hide from incoming fire. Characters snap in and out of cover or slide themselves directly into combat by alternating between tapping or holding the appropriate button; they fire guns, frantically reload, and toss grenades and molotov cocktails; if they knock an enemy over they can execute them with one of several different finishers, leaving a hapless mobster—gurgling from a slit throat or aerated by bullets—in a bloody heap. The pace is often relentlessly quick. Enemies rush in from out of view and the player can choose to either confront them directly with a pre-emptive attack or fight them off from cover as they advance ever closer.

At other times (especially in the game’s lengthy and much more difficult final levels) samurai and ninja capable of killing with a single, lightning-fast hit necessitate greater caution and a slower pace. When the action’s speed relents, though, it becomes no less frenetic: the player’s mind must continue to solve micro-puzzles of enemy spacing, distance to cover, and the number of bullets left in a dwindling magazine. The rhythm of Not a Hero is hypnotic, fast enough that the instinctual brain is engaged, but with enough elements requiring consideration that the higher mind is constantly active, too.

The game’s characters, from the shotgun carrying Cletus to the oversexed Spanish intern Jesus, not only stand apart in the way they play, but through their personalities, too. Cletus, picking up a special weapon, will mutter a nonchalant, Scots-accented “pure magic.” When selecting Steve as a character, he’ll offer a halfway resigned “Going door to door, canvassing and murdering.” The comments voiced by BunnyLord’s supporters are consistently funny, in an understated sort of way. They also create a tone of apathetically considered violence that fits neatly with the worldview established during Not a Hero’s pre- and post-mission story beats.

he has nothing to offer to his city but a few memorable headlines

Level briefings see BunnyLord, standing next to a projector screen that flashes PowerPoint-style infographics, detailing the upcoming job. He fills every one of his sentences with nonsense adjectives, promises milkshakes as a reward for a hard day’s work, and reveals his profound lack of intelligence at every opportunity (“Clive, I learned a new word today: aquarium”). The aimlessness of his crime reduction strategies and careless enthusiasm for bloodshed show that, really, he has nothing to offer to his city but a few memorable headlines. But he knows exactly how to get its populace to think he does.

The inevitable voting scene that wraps up the game sees a crowd of excited voters decked out in BunnyLord t-shirts, eager to make their voices heard. They’re pumped up about casting their ballot, even though they can’t have any real idea what they’re helping support. After all, not even BunnyLord himself seems to know what he’s trying to accomplish other than “become mayor.” But they’ve turned out to perform their civic duty, penning an “X” next to the one name they’ve become intimately familiar over several weeks of extra-judicial campaigning. The player watches this knowing all too well how hollow and bloody the work leading up to this moment has been. They see an exaggerated version of the worst tendencies of real-world democracy played out in vivid colors, all to the tune of relentlessly upbeat chiptune. Not a Hero’s ultimate statement is a brutally cynical one, but its political nihilism is always portrayed with such glee and good cheer that the unease is hard to feel until the game is shut down.