Nova-111 defies our obsession with genre

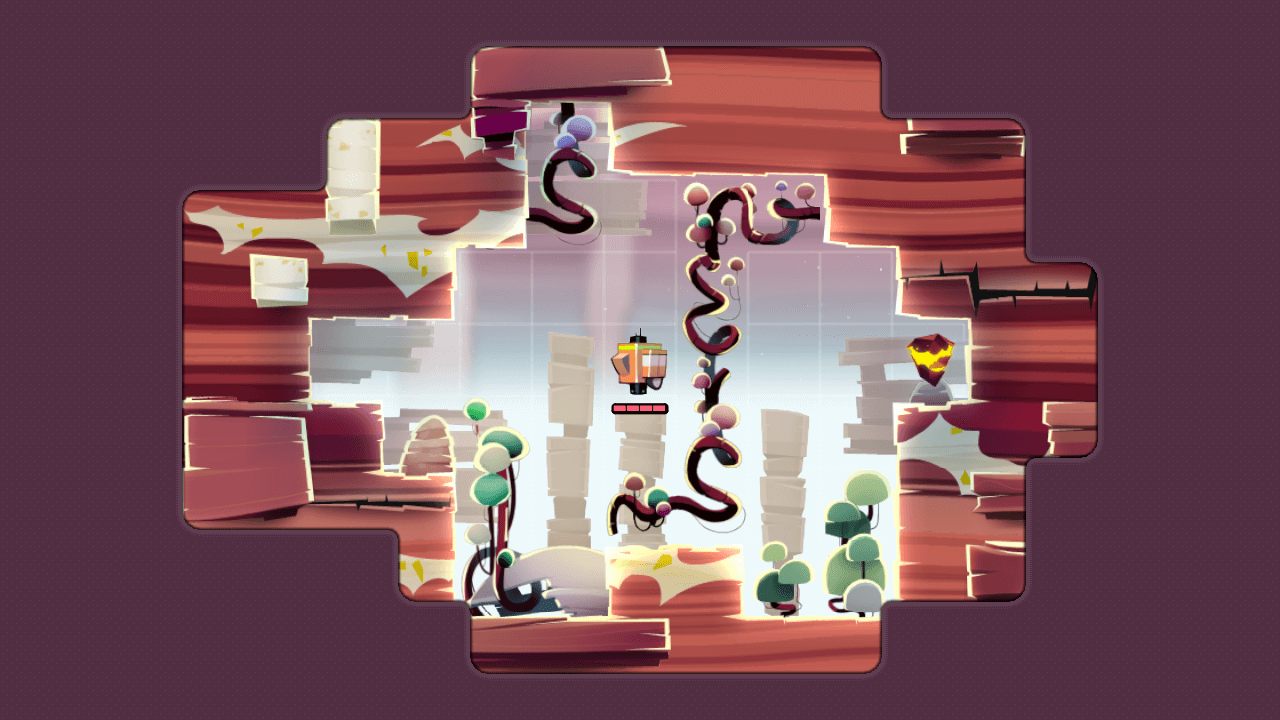

Genres are tough in games—some make an attempt to describe a title’s single dominant action: “platformers” have platforms, and in “shooters” you shoot. But there are tons of games that slip through those cracks and end up branded “strategy” or “action-adventure,” as if those can effectively communicate how it feels to play a particular game. The developers of Nova-111 call it a “turn-based adventure game,” but that’s equally hollow. Nova-111 is hard to pin down not just because it plays fast and loose with tropes we’ve seen before, but because the decision to blend real-time and turn-based play styles sets it apart from anything else it would otherwise resemble.

“Procedural Death Labyrinth” popped up as a tongue-in-cheek genre when people got tired of pointing out that games like Binding of Isaac and FTL aren’t so much roguelikes as they are “roguelike-likes,” lacking the grid-based movement and turn-based action that defined the genre’s namesake, Rogue. Nova-111 doesn’t have permadeath, nor does it have randomly constructed levels—in fact they are very obviously crafted to have complex puzzles—but it is a labyrinth, at least, and it does operate on a grid, and has (some) turn-based action. But it’s not a roguelike-like-like—that would just be ridiculous. It’s a rare bird, at once calling to mind a lot of other games and feeling resolutely like its own thing.

Nova-111 is a little like single-player speed chess—you aren’t given the time to look even ten moves ahead, so you make a good guess, and you move fast, one grid-square at a time. Sometimes you back yourself into a corner and you have to work a little harder to get out. Then, instead of losing key pieces and seeing the end coming a longer way off, you get surrounded and killed by aliens all at once, and you start the level over.

Nova-111 is a little like single-player speed chess

Like Braid before it, Nova-111 really does force the player to think in a new way. It keeps introducing new tools, new enemies, and new combinations thereof, to complicate and force you to rethink whatever has worked so far. By the end of the game, you can freeze time, but there are specific areas where enemies and stalactites move only during frozen time, and navigating that with the normal enemies still on your heels becomes even more difficult. In the burning laboratory, I loved zipping around dodging alien bullets and trapping baddies behind fire doors, narrowly avoiding getting singed myself. The combinations of enemies and environmental hazards force the player to be creative with her solutions, but think on her feet.

When this works, it works incredibly well—it’s exciting and makes the wheels in your head spin as you tear through a level—but sometimes the game introduces new elements so quickly that it hasn’t fully explored everything they can do before they disappear. In the last stages, everything comes together so cleanly and intriguingly that there have to be more ways these tools can fit together. This feeling that not everything is fleshed out extends past the moment-to-moment play, too.

The best measure of success in Nova-111 is whether or not you survived the level, but the game also gives you a timer and a move-counter for each stage, as if to encourage repetition—that you might play again and again to improve your placement on the leaderboards. The levels are big, though, and divided into smaller stages that can’t be individually selected, and anyway there are so many secrets and collectables in the levels that it seems like the game must want you to explore, not focus on the fastest possible route to the exit.

Most of the time it’s thrilling, but Nova-111 still wants to hold on to collectables, time trials, and block-pushing. Its clichéd “rescue the scientists” story aims high, at a Hitchhiker’s Guide sort of humor, but the “quirky” element feels forced—when lead scientist Dr. Science isn’t giving you tips, he’s telling you he really likes sandwiches and has unresolved issues with his mother. It’s worth enduring because what’s most impressive about the game is how different it really is. Plenty of puzzles or action games make great use of genre tropes that already exist, honing their own specific play-styles, but Nova-111 wants to skip all that and teach its players new ways to think about time and turns.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.