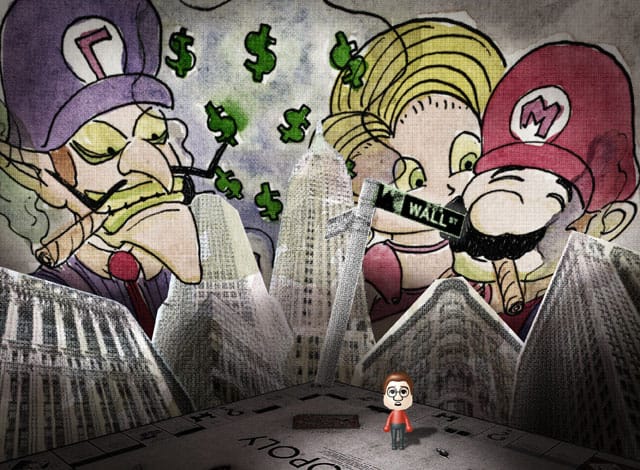

Occupy Fortune Street

Fortune Street was released late last year in America, at a time when hedge fund managers were less popular than Occupy Wall Street riot police. (After all, the police were only doing what they were told.) I suppose Fortune Street’s target audience won’t notice the layer of unintentional satire amidst all the hoopla. This is a game where Mario and company get together to play a souped-up version of Monopoly. Mini-games abound. Wii Remotes are shaken like maracas. The melodies of Dragon Quest chime over a courtyard of Miis. The only political opinion known by the age group Fortune Street most appeals to is the one that Daddy spouts off while watching the nightly news. For the rest of us, we get the unrequested chance to live a day in the life of the One Percent. Watch as Donkey Kong recklessly inflates the value of his real-estate investments, crossing the finish line before the housing market takes a plunge. Listen to Wario guffaw as his thoughtless actions cause the bank to foreclose, booting the working class from their homes.

If I didn’t know better, I’d say that Nintendo is trolling us. Yet the games from the Japanese publisher always exist in a bubble. Opposed to the housing bubble, its bubbles are nice, safe places that are far removed from the cares of everyday life. By a twist of fate, Nintendo has brought over a game that is relevant to current times, but in the worst possible way. In Fortune Street, the rich play an exclusive game of exploiting the economy—an aim that couldn’t be less popular in public sentiment. The goal is to become the wealthiest mascot on the block by paving over the hood with luxury condos and sushi bars, and engaging in what amounts to insider trading. Perhaps this is so the “Princess” can buy another castle, or build a private island in Dubai in the shape of a mushroom.

Nintendo has brought over a game that is relevant to current times, but in the worst possible way.

This long-running Japanese series has been ripe for localization for 20 years, but now that it is finally here, the West has changed. This must be how the Joads felt once they arrived at the New Deal camp in California. A game about high-rolling on Wall Street would have been a hit circa 2007. Nintendo’s stock was at an all-time high, the Wii business was booming, and the outlook on almost everything was BUY. Nowadays, people don’t want to romanticize about the free-wheeling lifestyle that got them into this messy recession. They want to hear Woody Guthrie sing a folk song about a loved one who died of dust pneumonia. They want a game where they toil in the dirt.

Just look at the success of Minecraft, a game that is more a jalopy than a Rolls-Royce. Style isn’t even considered. The graphics are incredibly low-budget. The game was released in alpha and has undergone constant repairs ever since. It is decidedly blue-collar. If it had a bumper sticker, it would read: Life Is Hard. Get To Work.

Minecraft’s ideology is, at heart, the American Dream. You’re settling in an uninhabited place. The land is barren and savage, but if you keep chopping wood, one day you’ll have a two-story house surrounded by a white picket fence. You might even strike gold. On Fortune St., however, every city block is occupied by a bakery, a deli, a department store, or some other property that is owned by the Man. Your operation is to short-change three of your friends (or three computer-controlled bots, because no one wants to play this game) in a race to get around the board and back to the bank. Similar to passing Go, doing so nets you a “promotion” and a raise. As in Monopoly, the best strategy for winning is to buy every property you land on. Unlike Monopoly, you have the added option to buy stock in any district you want. It goes without saying that the iconic pieces—the top hat, the thimble, the old shoe—are gone. They have been replaced by the cast from Super Mario Bros. And Dragon Quest. (What?) A typical lineup looks something like this:

Me: I play as a slightly outdated version of myself. This is the Mii I created when I got my Wii and haven’t bothered to update with facial hair since. The likeness is pretty accurate: an average white guy.

Waluigi: Or should I say “Wall Street” Luigi? He is Luigi’s taller, sinister counterpart. I don’t know his backstory. Maybe he is Wario’s brother. He has a handlebar mustache and wears purple. He looks exactly how I imagine a greedy Wall Street banker.

Mario: Remember the Mario you love? Well, this isn’t him. This is Newt Gingrich incarnate. He can’t be trusted. He is among the privileged, and I could swear that he cheats. He campaigns as a Washington outsider against the “elite,” although he has been on Freddie Mac’s payroll since he resigned as Speaker in 1999, during which time its stock price plummeted from $100 a share to around 0.20 cents.

Bianca: I vaguely remember her from Dragon Quest. She looks strikingly similar to Callista Gingrich, Newt’s third wife.

I don’t mean to say that beating the system is impossible. It just requires an incredible amount of luck. And I’ve never seen it happen.

The other three are usually guzzling champagne and caviar and managing their portfolio, well on their way to becoming kingpins, while I’m rolling ones and twos. By the time I get to the bank to cash my paycheck, they will have been around the board twice, meaning that they each now own twice the number of properties that I do, and the board is a minefield of overpriced hotels and cafes that charge three bucks for a cup of coffee. On this risky venture, my fate, and my pocketbook, rests on the roll of a die. I should be fine, I assure myself. Everyone is playing by the same rules. Only somehow, they’re not. By the time I make it around the board another time or two, I’m bleeding money. Waluigi owns a borough as expensive as Manhattan. Bianca is a real-estate giant. Meanwhile, I’m astounded when my turn doesn’t end with the jingle of loose change, because there is a hole in my pocket. Before long, I have to start selling off my scant investments to get by, while my affluent neighbors, who by now have doubled and tripled my net worth, lick their chops at the foreclosure auction.

At this point, a comeback is out of the question. The odds are stacked too high against it. I’m drawing unemployment, working odd jobs, and merely occupying space, while my overlords are battling it out for control of the world’s financial system. They are always lucky, and they always make the right move. I don’t mean to say that beating the system is impossible. It just requires an incredible amount of luck. And I’ve never seen it happen. Once, when I was playing against a friend, it seemed certain that he would win. I was out of the contest, as usual, but all he needed to do was round third base and come on home. Simple. Imagine his surprise when Newt, I mean Mario, drew a card that sent him from third place to first, landing him directly at the finish line. When I asked him how he did so well, despite the cheap loss at the end, he told me, “Stocks?”

He didn’t know how, and I don’t have a clue why I always lose. Some might claim I don’t know the strategy. To that, I say: What strategy? This is a game where the mood of the market swings on an errant die roll; where your entire financial plan can be defeated by the spin of a carnival wheel. Diversity will not save you. The only ones who have a foothold are those whom the system is built around: the computer-controlled billionaires. You could make a similar case for the confusion surrounding the Occupy movement. The 99 percent doesn’t know what to protest because that happens behind closed doors: at lobbyist dinners, in hedge-fund management meetings, and in congressional committees. They just know they are getting screwed. Waluigi wouldn’t be on the cover of Forbes if the system didn’t allow him to stick it to me for every extra cent. I don’t mind losing. The problem is when someone else wins at my expense.

Illustration by Daniel Purvis