On the Other Hand

This article was funded with support from Longreads members.

* * *

Summer, 1990. Steve Whitmire was inside his home north of Atlanta when he received a package in the mail. He pulled the contents out of the box. He stared at the mouth, the hands, the green felt body and limp legs. He smelled … his friend and colleague, Jim Henson. Months after the public memorial, and after Henson’s body was cremated at Ferncliff Cemetery and Mausoleum, this empty, lifeless form held the slightest scent of his famous creator within its frog-shape, first stitched together nearly forty years prior. A teen Jim cut scraps from his mother’s old turquoise coat and accidentally started an empire. Now the familiar face stared back at Steve, its mouth open for no reason. Henson’s son Brian and then-interim company president was asking Whitmire to continue his father’s legacy. Whitmire was 30 years old. He stuck Kermit in a cupboard and did not look at him for weeks.

Jim Henson died early in the morning on May 16, 1990. His creations entertained children and their parents even before joining Sesame Street in 1969, developing The Muppets into unlikely felt superstars. With his trademark beard and 6-foot-3-inch frame, Henson appeared from a distance like a lanky, affable lumberjack. As a human, he was charming and driven, ambitious yet calm. But as one of his puppets—strange creatures that beguiled audiences into learning and loving a bit more than before—he became something else. When he died, so too did the voice and body of bathtime-loving Ernie and Kermit the Frog.

Of course, Ernie and Kermit didn’t die. A puppeteers’ job is to make an audience forget he or she exists. The most well-loved proprietor of an art form hinging on not being visible could no longer hide, because he was gone. Someone else had to hide for him.

Since November 1990, Steve Whitmire has performed as Kermit, Ernie, and dozens of Henson’s famous roles, among the most well-loved and recognizable characters of the last half-century. Before that he spent over a decade inhabiting Thogs, dancing food, singing chickens, and Fraggles. Yet outside of Muppet fanatics and industry insiders, Whitmire is relatively unknown.

As part of the pre-launch media rush for 2011’s The Muppets, the first feature film since Disney bought the characters from The Jim Henson Company, journalist Steve Marsh wanted to interview Whitmire. Disney wouldn’t allow it. Instead, Marsh got to interview Kermit while Whitmire stood there, his hand answering questions his own mouth could not. Marsh snuck in a meta-query: “What are the differences between working with Jim and working with Steve?” Kermit answers: “Boy, it’s hard for me to tell. They both have very warm hands.”

Whitmire is relatively unknown

For the duration of Henson’s life, he was the only puppeteer to handle Kermit. “Kermit was Jim.” That’s Bernie Brillstein, Henson’s longtime agent, talking about the plot of 1979’s The Muppet Movie and the close similarities between the main protagonist and his human performer. This synchronicity would only strengthen. In an interview with The Washington Post in 1977, Henson explained how, “[Kermit] is the only one who can’t be worked by anybody else, only by me.” In Brian Jay Jones’s extensive Jim Henson: The Biography, Jones writes, “The more Jim performed Kermit, the more the two of them seemed to become intertwined … it was becoming harder to tell where the frog ended and Jim began.”

But what happens when one is no longer with the other? The unfortunate truth is that Jim ended; now the frog would have to begin again. If Kermit was Jim, who, then, is Steve?

* * *

Sesame Street first came on the air when Steve Whitmire was 10 years old. A pre-teen wouldn’t normally tune in; luckily, Steve’s brother Mark, six years younger, was closer to the target demographic. But it was the elder Whitmire who became rapt with the show and its cloth citizens. He wrote a letter directly to the person responsible for the characters, these “muppets.” Jim Henson wrote back, encouraging him to build his own, including patterns to help get him started. When other kids enthused over getting a new BB gun or Radio Flyer for their birthday, young Steve boasted of his latest gift: a sewing machine. His mother was a seamstress and passed on her talents to her first-born son. While classmates practiced tight spirals or studied trigonometry, Whitmire made puppets.

By high school his closet was filled with them; when he ran out of room in the house, he stuffed puppets in a plastic tub and stored them in a backyard shed. In 1976, during his junior year at Berkmar High School in Lilburn, Georgia, Whitmire met a new student named Gary Koepke, a kindred spirit who built a ventriloquist doll during his first day in shop class. The two soon found each other. “He made a puppet for me one time,” Koepke told me. “It was a baby. [Steve’s] mom crocheted the booties and bonny for him. One of the girls in school just got a haircut … so he took clippings and glued it on for hair.”

Whitmire made puppets

Whitmire has always had an enviable coif; that he remains hidden under a raised platform while performing, those healthy locks invisible to millions of unassuming fans, is one of the great injustices of the television era. As a senior, he had the longest hair of any student, male or female. Halfway through that year, a new girl named Melissa moved to town. Word spread. “I bet your hair is longer than Steve’s,” her new girlfriends said. “Steve who?” she replied.

“They actually got in a room,” Koepke told me, “and they met because they measured their hair.” Turns out Melissa’s was one inch longer. They ended up dating. According to Koepke, Steve knew right away they were going to get married. (They would a few years later, and she’s been his business manager nearly ever since.)

Whitmire has never lacked confidence. He often helped the high school drama club with their makeup and props. One day he tested his technique. So he created and applied a thick animalistic mask, turning himself into a character from The Planet of the Apes. He and his friends went to Northlake Mall; they put a leash on him and he jumped all over the grounds, eating plants and amusing passersby. Most high school students didn’t have the urge to turn into a different person. Whitmire actually did.

Steve knew right away they were going to get married

Reinvention is inherent to puppeteering. In fact, Whitmire’s ultimate reinvention was presaged over a decade before he took over for his mentor and hero.

Koepke, a year older than Whitmire, had a job performing puppetry at Six Flags Over Georgia. One day he invited his fellow enthusiast to the park; Whitmire aimed to make an impression and land a job there, too. He came prepared. Between acts, he climbed up on the puppet stage and ducked behind the parapet to a child-sized castle. Soon, “Jim Henson,” his long legs and bearded face in full puppet form, was singing and dancing upon the castle walls.

* * *

In his twenty five years and thousands of appearances as the frog, Whitmire’s Kermit has taken on a slight evolution, growing with his newfound caretaker. “The number one goal in trying to continue a character like Kermit,” Whitmire explains in a behind-the-scenes interview from 2010, “was to make sure the character stayed the same and consistent, but didn’t become stale and just a copy.” Henson would bend the frog’s nose down to the floor to convey hurt or dismay; Whitmire doesn’t exaggerate, instead tilting the green guy’s nostrils down slightly. Watching Whitmire perform Kermit is the same as hearing a talented pianist take on Rachmaninoff. But Steve (a musician himself) is not playing Henson’s notes; he’s playing Kermit’s.

That same year, Whitmire gave a series of lectures called “The Sentient Puppet” at the Center for Puppetry Arts in Atlanta. They were, ostensibly, workshops for budding puppeteers, Whitmire’s lessons peppered with a mix of philosophy and memoir. Puppeteer Liz Vitale and her husband were in attendance, their notes the only public record of what was said. All Muppets have an appearance of life, he explained, “an organic existence.” He referred to them as “conscious inanimate objects.”

Older stewards of Henson’s legacy have long spouted similar phrases. In a video recorded for internal use in 1990 and made public years later, longtime Muppet designer Michael Frith is sitting with Henson and Frank Oz, famed puppeteer and now-director, as they discuss the intricacies of Kermit’s design. “There’s a sense of aliveness,” Oz says, as he describes Henson and the puppet co-existing somewhat separately from the other: “As Jim is sitting there, Kermit is just casually looking around and just quietly nodding and listening.” Indeed, as the camera zooms in and cuts off Henson from the frame, Kermit goes from a puppet on its performer’s arm to a believable entity. “They have a life of their own,” Oz says.

What separates puppetry from other performance art forms is how these two lives intermingle. Miss Piggy began as a one-off character in a skit called “Return to Beneath the Planet of the Pigs” from the 1975 special The Muppets: Sex and Violence. When Frank Oz put her on and delivered an impromptu karate chop during season one of The Muppet Show, the character as it is known today was born. As a marionette artist, you’re manipulating strings. As an actor, you embody a character. As a Muppet performer, your arm is the body; your hand is the mouth. Though you’re unseen by the audience, every move you make is translated directly into this other entity that exists because of you, but also outside of you. “Muppets are motivated by real feelings, memories, thoughts and emotions,” Vitale wrote during Whitmire’s lecture. “They are not a ‘what,’ but a ‘who’.”

That is why Henson’s first show in 1955 was not called Jim and his Puppets but Sam and Friends, with top billing going to the orange doll with big ears and a clown nose. Twenty years later, Henson’s The Muppet Show launched on CBS to raves.

Earlier that summer, in 1976, an 18-year-old Whitmire joined Koepke on a long car ride to a ventriloquist convention in Kentucky. While Koepke drove his Ford Pinto, Whitmire stitched together a new puppet, a bearded hippie wearing tie-dye and jeans. The long hair and easy-going attitude matched Whitmire’s own. Otis was born.

As Henson and the gang filmed The Muppet Show in London, Whitmire began hosting The Kid’s Show with Otis on Channel 36-WATL. Koepke soon joined him as co-host. The office building where they filmed had ceilings eight feet high; the two would lie on their backs, holding the puppets up into the camera’s view. They were live on-air for two and a half hours. Nothing much was planned; the two would improvise and banter. In one show, Otis lambasts Koepke’s Grunch, a friendly if inelegant monster, for buying a pumpkin the day after Halloween.

Other times they’d riff on local events. The morning before Muhammad Ali fought a charity event downtown, Whitmire dressed Otis in tiny boxing gloves and a shiny robe and challenged the champ on-air, telling him to call in and talk to the audience, “for the last time… before we punch out your vocal cords!” A number flashed on screen asking viewers to vote: “Otis or Ali?” Ali’s manager got wind of the stunt and called the office; that evening, Otis was ringside, Ali chiding him that he looked like Joe Frazier.

Otis was ringside, Ali chiding him that he looked like Joe Frazier

But the main draw was a recurring segment where kids called in between black-and-white serials to speak with the puppets. Whitmire, still on his back, would wield Otis with one hand while punching in callers on the landline with the other. Boys and girls asked questions or shared stories. One frequent caller read Otis a poem he had written. “I love you, Otis,” he began in a sweet pre-adolescent tenor, “I love you the mostest.”

The following year, Whitmire attended an annual puppetry convention being held in Atlanta. He met Caroll Spinney, otherwise known as Big Bird and Oscar the Grouch. Spinney recognized the kid’s passion and talent; he encouraged Steve to reach out to Henson. Whitmire cold-called Henson Associates in New York and was told to send an audition reel. On November 7, 1977, on WATL-TV Atlanta Channel 36 stationary, Whitmire typed out the following:

“Dear Friends, Romans, and Muppets:

This is a video cassette (as if you didn’t know). Included are some of the excerpts from ‘THE KIDS SHOW WITH OTIS’, my local kids show. I hope that they will be satisfactory for your viewing.

Please return the tape as soon as you view the material.

Hope to hear from you.

Yours truly,

And here he signs his name, with grandiose loops and curves that echo Henson’s own famous signature-turned-logo.

Steve Whitmire

(and “Otis”)

A hand-and-rod puppet named Spunky introduces the reel. “What we’re hoping to show you by this is what the guy down here can do,” the toad-like puppet says, gesturing below the table where Whitmire sits, unseen. Spunky approaches the camera conspiratorily. “Let me tell you in advance: Don’t expect too much. He’s not really very good.” Steve’s free hand flies in from off-camera and tries to muzzle the puppet. “And besides that he’s very mean!” Spunky yells, before being throttled and dragged away.

The Hensons were intrigued. Jim’s wife and business partner, Jane, was flying to Atlanta to supervise a Kermit float to be used during the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade. She asked Steve to meet her at the airport for an interview. In the terminal, Whitmire pulled out Otis from his duffel of creations. And the children flocked. This was their favorite TV character right in front of them; the long-haired teen attached made no difference. Unbeknownst to them, they were seeing one of Otis’s final performances.

Mrs. Henson, suitably impressed, recommended her husband speak with Otis’s handler over the phone. Whitmire was so excited when Henson called he recorded the conversation by attaching a suction cup microphone to the receiver. He was still just a kid, one year out of high school and now talking with his hero. Henson would soon be his boss. By the next spring, Whitmire would be in London himself, a background performer on The Muppet Show.

* * *

New puppeteers don’t take over a new character right away; instead, they perform “right hands.” Since most performers are right-handed, and the dominant hand offers more control and dexterity for a puppet’s mouth and head, their left hand controls the character’s left arm, which means the right arm remains limp. So a secondary performer assists, matching up movements with the help of a live monitor showing what is on screen. The two need to synchronize perfectly for any semblance of believability. The scenario reveals another substratum of identity crisis that awaits any puppet performer. An actor portrays a character, but that’s still your face and body the audience sees. A puppeteer is invisible save their manipulations covered in cloth.

Until Being Elmo, the documentary about long-time Elmo performer Kevin Clash, nobody knew who Clash was. Elmo was just Elmo. Consider the secondary performer, the underling to the already-invisible: They don’t play a fictional character; they gesture a single limb. That dark empty sleeve is the foxhole of puppeteers—you dig in, protecting your neighbor and hope you come back alive. Survive and your own identity awaits. Jerry Nelson began as a right hand for the Muppets in 1965—eventually he would perform one of the most recognizable Sesame Street citizens, Count van Count. If anyone knows the value of digits, it’s a 4-year-old learning their numbers by extending one finger at a time until, finally, their hand is open, the better to grab on.

Whitmire graduated from right-hands with Rizzo the Rat; born as a nameless part of an ensemble, Whitmire’s take on the feisty rodent soon earned him more screen time and a first name. Throughout the Eighties, Whitmire slowly rose through the ranks of Henson’s performers; alongside a litany of Muppet Show roles, he assisted in 1982’s Dark Crystal, 1986’s Labyrinth, and earned the role of Wembley in Fraggle Rock.

For 1989’s The Jim Henson Hour, Whitmire was asked to perform a new kind of puppetry, one forged by the blending of computers and old-fashioned hand manipulation. He used a remote-control device to make a small bird-like creature named Waldo C. Graphic speak, gesture, and move; but instead of wires connecting Whitmire to a physical thing, the sensory information was loaded onto a computer and the result was a high-resolution image that could be placed in a scene in post-production.

Though The Jim Henson Hour was a swift failure, such advancement of the craft pushed an ancient artform into the Information Age without neglecting the human touch necessary to breath life into these “conscious inanimate objects.”

Puppetry has always relied on a suspension of disbelief. Or, more optimistically, a sustaining belief in the object having a life of its own. It is fitting, then, that on May 21, 1990, at the Cathedral Church of Saint John the Divine in New York City, where the public came to mourn Henson, the Muppet performers shed their animal skins and sang a medley of Henson’s favorite songs, not as lip-synching puppets, but as grieving friends.

Watch the memorial service and one performer stands out immediately: Whitmire’s long blond curls hang atop a brightly colored outfit. In a letter written to his children long before illness took him, Henson requested nobody wear black to his funeral. Whitmire didn’t know then that he’d be pegged to replace his boyhood idol. Even so, on the day the nation celebrated Henson’s life, Whitmire wore an emerald suit fit for a swamp king: green pants, green shirt, green suit, with a green boutonniere and, around his neck, the pointed collar worn by The Frog himself.

* * *

Puppetry has often straddled the line between reality and make-believe. Special puppets called Sa’lakwmanawyat, or “dolls,” form an important part of the Native American Hopi tribe’s belief system. A doll is taken care of by a host family. They do not consider the doll as a static object but more like a person, with identifiable traits and feelings all its own. Basil Jones, co-founder of Handspring Puppet Company, whose designers and puppeteers were responsible for the mechanical equestrians of the 2007 Broadway hit War Horse, believes strongly in the work of purposeful reanimation. Speaking to John Fleming of the Tampa Bay Times in 2013, Jones said, “As human beings we hate the idea that things die forever, and we love the idea that things can be resurrected. I think puppetry is an act of resurrection.”

That feeling looms large at the Center for Puppetry Arts in Atlanta, home to the largest puppetry archives in the nation. The three-story former schoolhouse is undergoing a massive renovation slated for completion this fall. Its museum already features over 2,000 pieces from every continent. The big draw, though, will be the new Jim Henson Collection, making public Henson’s immense portfolio of creatures and props, donated by his family in 2007, some stuck in closets for decades.

But what about the man himself? When I visit the Center, the librarian’s archivist shows me where I can find him. “Jim is here,” she says, pointing to a box three shelves up, “and here,” pointing one over. Inside the folders are clippings from newspapers and magazines; pamphlets from puppetry conventions; in one case, a Xeroxed handout distributed to fellow performers titled “A Brief and Illustrated Dissertation on the Making of Muppets for the Delectation of Our Friends and Correspondents.”

Puppetry has often straddled the line between reality and make-believe

An issue of Woman’s Day magazine from December 1969 features “an original Christmastime puppet play,” written by longtime Muppets writer Jerry Juhl. Henson’s designs were still mostly abstract back then, more colored socks with googly eyes than recognizable creatures. Such simplicity allowed anyone to make their own; on page 100 of the issue, each Muppet design is laid out on graph paper for the reader to copy. A young Whitmire likely used just such a template to make his first puppet.

Henson’s brilliance was not only in creating the puppets themselves, but in delivering his creations to millions at a time through the burgeoning technology of television. Henson wasn’t the first to bring puppetry to the masses, but he was the most fearless, playing with conventions that ultimately gave way to a singular, new way to educate and entertain.

“What the world knows about puppets is really what Jim Henson opened to them,” Vincent Anthony told me. Anthony founded the Center in 1978; Henson and Kermit the Frog were on hand to cut the ribbon. The year before, Anthony was elected president of the Puppeteers of America, a position Henson held from 1962 to 1964. “We were friends. He had a circle of people around him. And somehow I managed to get into that circle.”

For the 10-year anniversary of the Center in 1989, Anthony organized an event called “Muppets Take Atlanta!” It was one part puppetry celebration for the public, one part thank-you to donors and board members who helped keep the Center afloat. In the Center’s archive, I watch a VHS recording of that show’s rehearsal with Henson, Kevin Clash, and local product Whitmire. A dull hum mars the audio. The Muppet performers are wearing all black and comfortable shoes. They run the big finale, a musical number to “La Bamba,” close to a dozen times. Around the sixth repetition, Henson is holding Kermit but talking in Rowlf’s voice through the frog.

Such simplicity allowed anyone to make their own

“You might not think this is Rowlf,” Kermit/Jim says, “but it is.” Clash pipes in with his inimitable high-pitched Elmo voice but holding Leon, a new puppet from the Henson Hour: “Hi I’m Elmo! Who are you?” Whitmire, using another new puppet named Bean Bunny, says something unintelligible on the tape, but it gets a big laugh. Later, listening to the music one last time, the three sit on stools without their puppets. Jim holds his knee. Steve taps his leg. Eventually Steve starts moving his right hand like a mouth, lip-synching to the words. Jim keeps holding his knee. He’s practiced enough.

A young ventriloquist named Jeff Dunham opens the show. Then Anthony introduces “the Muppet genius,” Jim Henson, who speaks to the crowd and shows a few clips from their newly on-air Jim Henson Hour before bringing out Clash and Whitmire. They close the show with “La Bamba,” a cavalcade of puppets taking turns singing, dancing, and goofing up the lines.

Anthony still remembers when he first heard of Henson’s passing. “I was in bed. I turned the radio on. I was half sleeping,” he says, his memories clipped and short. “And I remember an announcement coming over, saying they are announcing Jim Henson’s death. It was a shock.”

Anthony learned of Whitmire from his local TV show in the ‘70s. The two still work together; Whitmire auctioned off much of his personal collection of career souvenirs to help raise money for the Center’s renovation. When asked about Steve performing Henson’s roles, especially Kermit, Vincent calls it a “flawless transition.”

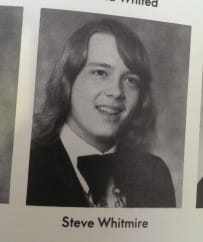

“I know it was a dream job for Steve,” Henson biographer Brian Jay Jones said in an email to me. As far back as 1976, two years before joining The Muppet Show, Whitmire aligned himself with the famous character. High school friends called him “Kermit” due to his impromptu puppet routines. His senior year yearbook included a section called Last Will and Testament, where graduating seniors could say their final goodbyes. His begins thusly: “I, Steve Kermit Whitmire, being totally froggy …” before remembering his rock band (named FULL SUN) and an unrequited crush (“a love that can’t be suppressed…”). In the yearbook index, his clubs and organizations are listed: Thespian Member, Men’s Chorus, and then something called KSW, Inc. No other student lists the same. This was an exclusive club, after all: Kermit Steve Whitmire, Incorporated.

* * *

We’re on the cusp of a tangible renaissance. After two Muppets feature films, a new weekly show debuts on ABC this month. A movie based on Fraggle Rock, where Whitmire played the affable Wembley for five years, looks to be happening after several false starts. Hit musical The Lion King, with puppets created by Julie Taymor (who received a grant from the Henson Foundation as a young artist), is the highest-grossing Broadway production of all-time. Jeff Dunham is now a blockbuster act; his YouTube page has been viewed nearly 150 million times. And Star Wars: The Force Awakens opens this December, promising all sorts of droids and X-wings built by warm, calloused palms. Whitmire and his band of merry Muppet performers finally have plenty of company.

The most impressive specials effects are the ones we never realize are special. We take them for granted, believing without questioning. We believed in Jim Henson; we also took him for granted. A quarter-century ago, we lost a visionary to cruel chemistry, a bacterial invasion liable to strike any one of us. That this unpredictable fate chose Henson forces us to question what we’ve done with the last two and a half decades, and whether we’ve earned the extra time. Whitmire made good with his. And though he was not destined to be the next Henson, he was destined to keep Henson’s alter ego alive. Even if nobody knows it’s him under there.

“One of the most common misconceptions I encounter when talking about Jim,” Jones writes in an email, “is that everyone assumes Brian Henson is the one performing Kermit.” The eldest son took over Jim Henson Productions within a year of his father’s death. Brian was 27. He had previously worked some alongside his father, notably performing the dog in Jim Henson’s The Storyteller, but has since shifted his talents behind the camera, directing films and the company at large.

“I don’t think it ever even occurred to Brian to perform Kermit,” Jones writes. That didn’t stop people from assuming. In one of the many grieving articles around the country in the weeks following Henson’s death, Marilyn Beck wrote that the tragedy, “certainly won’t mean the end of his magical creatures on television… Brian Henson, Jim’s son and collaborator, will most likely carry on the tradition Jim began almost 30 years ago.”

We’re on the cusp of a tangible renaissance

And in a way, he has. Under the stewardship of the younger Henson, who became president in 1991 and is now Chairman, his father’s company continues to flourish when many thought it would die with its founder and namesake. David Owens’s 1993 New Yorker profile, “Looking Out for Kermit,” shows Brian as an unlikely but effective leader, making tough decisions while still in the wake of losing a father. (Elsewhere in the piece, Whitmire is shown in a glass recording studio, making chicken noises.) David Lazer, longtime Henson producer and friend, remarks on the surviving children: “He is living through them, in a way… When you speak to Jim Henson’s children, it is almost as though you were speaking to him.”

But when you speak to Kermit, you are really speaking to Steve.

* * *

Twenty-five years ago, on May 17, 1990, the future seemed a cold and dark place for many of us. For one bundle of green felt, that cold and dark place was a box stuffed in a closet.

Back in his suburban Atlanta house, gazing down at the forested valley below his double-decker wood patio, Steve Whitmire finally decided to join his swamp friend. Whitmire took Kermit out of hiding weeks after receiving him in the mail. He set up a camera and recorded Kermit singing “Bein’ Green.” This was the tape he’d send back to Henson Associates and the still-mourning Brian, ostensibly an audition to replace the towering founder and heart of an empire. Using his best approximation of Henson doing Kermit’s voice, Steve sang these words:

People tend to pass you over

‘cause you’re not standing out

like flashy sparkles in the water

or stars in the sky

But green’s the color of Spring…

Kermit’s central complaint in the song is about blending in, before realizing that same hue is what makes him beautiful. For Whitmire, nothing could be grander than “not standing out,” allowing his work to remain hidden behind the legacy of another.

On November 21, 1990, six months after the memorial service where he wore the famed green collar, Steve Whitmire first performed Kermit for the special, The Muppets Celebrate Jim Henson. The frog comes on to applaud the entire gang of Muppets—from across the Henson multiverse, from Big Bird and Miss Piggy to Dr. Teeth and Waldorf—for their singing.

Whitmire’s Kermit tilts his head slightly back and forth before speaking; subsequent airings used re-recorded vocals, dubbing over the original’s not-quite Kermit voice. His performance would grow more confident with time. But in 1990, Steve was a 31-year-old apprentice, taking up the master’s reins for the first time. Visible in the background of the scene, slightly blurred from depth of field, is a picture of Jim Henson.

At first it looks like a framed black-and-white photograph, or a still from a film reel. But then you notice the curved screen and 4:3 ratio. Kermit is standing in front of TVs stacked like bricks in a wall, each showing a paused scene from Henson’s work. There’s Jim, smiling and staring out of a frozen moment from his, and our, past, tipping a top hat as if in gratitude to the young man from Atlanta who shares his birthday and has, in no small way, kept his art alive for another generation.

Henson understood life as a joyful mess, a chaotic celebration of just being here; if it was up to the boss, the piece wouldn’t end on a note of sentimentality, or questions of rebirth or artistic intent. So quick, somebody: Cue the music! Cut to an explosion, or some mayhem, the more Electric the better. And the next time the curtain rises, Steve Whitmire’s right hand will open and Kermit will be singing again.

* * *

Jon Irwin is a teacher and writer living in Atlanta. His work has been published in Billboard Magazine, Down East, Lumina, Paste, and Transitions Abroad, and he’s been a contributing writer for Kill Screen since 2011. His first book, Super Mario Bros. 2, was published by Boss Fight Books in 2014.

* * *

Editor: Clayton Purdom; Fact-checker: Brendan O’Connor

Header images by Eva Rinaldi, Flickr and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Flickr

Whitmire on set image via The Disney Wiki

Whitmire yearbook photo from the Berkmar High School Yearbook, 1976

Whitmire Comic Con photo by Ewen Roberts, Flickr